|

|

| (33 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| <div class="article Learning_to_Experiment,_Sharing_Techniques layout-1" id="Learning_to_Experiment,_Sharing_Techniques"> | | <div class="article Learning_to_Experiment,_Sharing_Techniques layout-1 add-chaptertitle1" id="Learning_to_Experiment,_Sharing_Techniques"> |

|

| |

|

| [[File:Perfect-robbery-Experimente-lernen-cropped.jpg|thumb|class=title_image scriptothek|Caption]] | | <div class="hide-from-website"> |

| | [[File:Perfect-robbery-Experimente-lernen-cropped.jpg|thumb|class=title_image|How-to "The Perfect Robbery by Juli Reinartz," in ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook,'' edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).]] |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| <div class="hide-from-book scriptothek">

| | <div class="hide-from-book scriptothek">

|

| [[File:Experimene-Lernen-cover.jpg|thumb]] | | [[File:Experimene-Lernen-cover.jpg|thumb]] |

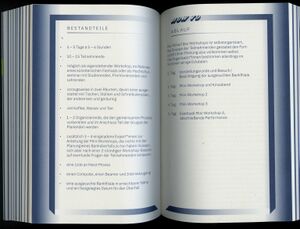

| [[File:Perfect-robbery-Experimente-lernen.jpg|thumb]] | | [[File:Perfect-robbery-Experimente-lernen.jpg|thumb|How-to "The Perfect Robbery" by Juli Reinartz," in ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook,'' edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).]] |

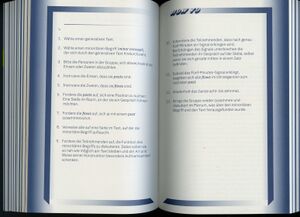

| [[File:Give-and-take-Experimente-lernen.jpg|thumb]] | | [[File:Give-and-take-Experimente-lernen.jpg|thumb|How-to "Give and Take" by Social Muscle Club," in ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook,'' edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).]] |

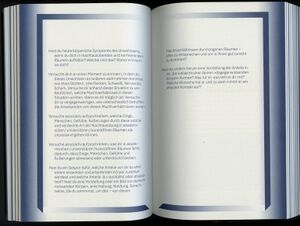

| [[File:Massumo-Experimente-lernen.jpg|thumb]] | | [[File:Massumo-Experimente-lernen.jpg|thumb|How-to "Conceptual Speed Dating" by Brian Massumi," in ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook,'' edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).]] |

| [[File:Body-Strike-Experimente-lernen-web.jpg|thumb]] | | [[File:Body-Strike-Experimente-lernen-web.jpg|thumb|How-to "Bodystrike" by Feminist Health Care Research Group," in ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook,'' edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).]] |

| [[File:Body-Strike-Experimente-lernen2.jpg|thumb]] | | [[File:Body-Strike-Experimente-lernen2.jpg|thumb|How-to "Bodystrike" by Feminist Health Care Research Group," in ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook,'' edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).]] |

| </div> | | </div> |

|

| |

|

| === Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques === | | === Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques === |

| <span class="author"> Julia Bee, Gerko Egert </span> | | <span class="author"> Julia Bee and Gerko Egert </span> |

|

| |

|

| <div class="block"> | | <div class="block"> |

| Line 20: |

Line 22: |

| “[S]tudy is what you do with other people. It’s talking and walking around with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three, held under the name of speculative practice. The notion of a rehearsal – being in a kind of workshop, playing in a band, in a jam session, or old men sitting on a porch, or people working together in a factory – there are these various modes of activity.”''<ref>Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, ''The Undercommons. Fugitive Planning and Black Study'' (Wivenhoe: Minor Compositions: 2013),110.</ref> </blockquote> | | “[S]tudy is what you do with other people. It’s talking and walking around with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three, held under the name of speculative practice. The notion of a rehearsal – being in a kind of workshop, playing in a band, in a jam session, or old men sitting on a porch, or people working together in a factory – there are these various modes of activity.”''<ref>Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, ''The Undercommons. Fugitive Planning and Black Study'' (Wivenhoe: Minor Compositions: 2013),110.</ref> </blockquote> |

|

| |

|

| “To study” is an activity—it combines teaching and learning, two activities that are usually considered separate. In the book ''The Undercommons. Fugitive Planning and Black Study'', Stefano Harney and Fred Moten set out to distinguish the collective activity of study from the study that takes place within educational and academic institutions. They point out that collective study happens while playing, making music, biking, discussing with friends, traveling. While teaching and learning in Western societies is deemed to take place within educational institutions, and is structured by evaluation systems, assessments, and grades, Harney and Moten show that study is by no means limited to these spaces. They argue that most study happens beyond institutional settings. Study is collective, sometimes you are a learner and sometimes a teacher, but often you are both. Teaching and learning do not just happen, they are not only emergent events, they are made possible through a series of techniques. Sometimes these techniques are visible, while often they go unnoticed. These techniques—rather than the institutions with which they are associated—are what we are interested in.<br> | | “To study” is an activity—it combines teaching and learning, two activities that are usually considered separate. In the book ''The Undercommons. Fugitive Planning and Black Study'', Stefano Harney and Fred Moten set out to distinguish the collective activity of study from the study that takes place within educational and academic institutions. They point out that collective study happens while playing, making music, biking, discussing with friends, traveling. While teaching and learning in Western societies is deemed to take place within educational institutions, and is structured by evaluation systems, assessments, and grades, Harney and Moten show that study is by no means limited to these spaces. They argue that most study happens beyond institutional settings. Study is collective, sometimes you are a learner and sometimes a teacher, but often you are both. Teaching and learning do not just happen, they are not only emergent events, they are made possible through a series of techniques. Sometimes these techniques are visible, while often they go unnoticed. These techniques—rather than the institutions with which they are associated—are what we are interested in. |

| | |

| | ==== ''nocturne'': A platform for teaching and learning ==== |

|

| |

|

| ====''nocturne'': A platform for teaching and learning====

| |

| Often, we meet scholars, artists, and activists who have developed ideas and pedagogical techniques in their personal practices and in dialogue with their students and workshop participants. In order to share these techniques beyond their initial contexts—classroom, studio, workshops—we initiated ''nocturne'',<ref>See [http://www.nocturne-plattform.de/ www.nocturne-plattform.de]</ref> a platform for experimental knowledge production across art, academia, and activism. It is a platform that grew from our curiosity and enthusiasm for the many experimental pedagogical formats that exist outside of dominant institutional settings. It brings together a series of techniques for experimental teaching sourced across the fields of art, performance, philosophy, theater, film, and media studies. Each contribution consists of a technique that was developed during seminars and workshops, and in studios and rehearsal spaces. The contributions include: a collaborative fabulation of a bansk robbery; the now familiar format of the reading group; writing workshops; collage; film essays; and a group performance. The platform is intended to offer an insight into the field of experimental and collaborative pedagogy. It is understood as open-source in the sense that it is an invitation to try, adapt, and further develop the techniques in other contexts. In this respect, by collecting and documenting the techniques, we are contributing to the continued circulation of knowledge that extends beyond institutional boundaries. | | Often, we meet scholars, artists, and activists who have developed ideas and pedagogical techniques in their personal practices and in dialogue with their students and workshop participants. In order to share these techniques beyond their initial contexts—classroom, studio, workshops—we initiated ''nocturne'',<ref>See [http://www.nocturne-plattform.de/ www.nocturne-plattform.de]</ref> a platform for experimental knowledge production across art, academia, and activism. It is a platform that grew from our curiosity and enthusiasm for the many experimental pedagogical formats that exist outside of dominant institutional settings. It brings together a series of techniques for experimental teaching sourced across the fields of art, performance, philosophy, theater, film, and media studies. Each contribution consists of a technique that was developed during seminars and workshops, and in studios and rehearsal spaces. The contributions include: a collaborative fabulation of a bansk robbery; the now familiar format of the reading group; writing workshops; collage; film essays; and a group performance. The platform is intended to offer an insight into the field of experimental and collaborative pedagogy. It is understood as open-source in the sense that it is an invitation to try, adapt, and further develop the techniques in other contexts. In this respect, by collecting and documenting the techniques, we are contributing to the continued circulation of knowledge that extends beyond institutional boundaries. |

|

| |

|

| Line 30: |

Line 33: |

|

| |

|

| These foundations are echoed in the techniques explored in ''nocturne''. Some techniques, like the contributions by Erin Manning and Brian Massumi, were developed in the context of one of the projects, while others, like Juli Reinartz’ or Inga Zimprichs engaged with this history more indirectly. | | These foundations are echoed in the techniques explored in ''nocturne''. Some techniques, like the contributions by Erin Manning and Brian Massumi, were developed in the context of one of the projects, while others, like Juli Reinartz’ or Inga Zimprichs engaged with this history more indirectly. |

| <br>

| | |

| <span class="page-break"> </span> | | <span class="page-break"> </span> |

|

| |

|

| <br>

| | ==== How-To… ==== |

|

| |

|

| ====How-To…====

| | In our first publication ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook''<ref>Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (ed.), ''Experimente lernen, Techniken tauschen. Ein spekulatives Handlbuch'' (''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook'') (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).</ref> we adopt the format of a “how-to” style manual to “document” the techniques included. By mimicking the how-to of a handbook we emphasize the pragmatic approach to every technique. It is a book to use. And yet its pragmatism does not equate with a goal-oriented approach. In fact, for us, pragmatism is a form of engagement that is attuned to an actual situation but not limited to it. To avoid pragmatism becoming a means to an end, we emphasize its speculative dimension. It may seem paradoxical at first to use speculation and pragmatism simultaneously. But the logic of speculative pragmatism<ref>Erin Manning and Brian Massumi. ''Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience''. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).</ref> allows us to think of techniques not as something one needs to earn or learn to master, but rather as a way to put into practice speculatively in the midst of an actual situation. Speculative how-tos, as we propose them, are open to appropriation. They are, in Brian Massumi’s words, “enabling constraints.”<ref>Brian Massumi, Brian and Joel MacKim. “Of Microperceptions and Micropolitics. An Interview with Brian Massumi,” ''Inflexions. A Journal for Research-Creation,'' 3 (2009), http://www.inflexions.org/n3_massumihtml.html</ref> |

| In our first publication ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook''<ref>Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (ed.), ''Experimente lernen, Techniken tauschen. Ein spekulatives Handlbuch'' [''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook''] (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).</ref> we adopt the format of a “how-to” style manual to “document” the techniques included. By mimicking the how-to of a handbook we emphasize the pragmatic approach to every technique. It is a book to use. And yet its pragmatism does not equate with a goal-oriented approach. In fact, for us, pragmatism is a form of engagement that is attuned to an actual situation but not limited to it. To avoid pragmatism becoming a means to an end, we emphasize its speculative dimension. It may seem paradoxical at first to use speculation and pragmatism simultaneously. But the logic of speculative pragmatism<ref>Erin Manning and Brian Massumi. ''Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience''. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).</ref> allows us to think of techniques not as something one needs to earn or learn to master, but rather as a way to put into practice speculatively in the midst of an actual situation. Speculative how-tos, as we propose them, are open to appropriation. They are, in Brian Massumi’s words, “enabling constraints.”<ref>Brian Massumi, Brian and Joel MacKim. “Of Microperceptions and Micropolitics. An Interview with Brian Massumi,” ''Inflexions. A Journal for Research-Creation,'' 3 (2009), http://www.inflexions.org/n3_massumihtml.html</ref> | |

|

| |

|

| A technique that straddles the line between pragmatism and speculation in a performative way is [[#The_perfect_robbery|The Perfect Robbery]] by Juli Reinartz<ref>Juli Reinartz studied philosophy and dance in Berlin and choreography in Stockholm. Since 2012, she works as freelance choreographer. In 2012, she received a one-year residency at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm. Since 2019, Juli is conducting a doctoral research at Uniarts Helsinki in which she explores disorientation as a choreographic strategy. “Konturen” (2020) and “Yes Contours Time Disorientation xt”(2021) have put different performative structures into practice. “All late, all babe” will conclude the research in 2024.</ref> | | A technique that straddles the line between pragmatism and speculation in a performative way is [[#The_perfect_robbery|The Perfect Robbery]] by Juli Reinartz<ref>Juli Reinartz studied philosophy and dance in Berlin and choreography in Stockholm. Since 2012, she works as freelance choreographer. In 2012, she received a one-year residency at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm. Since 2019, Juli is conducting a doctoral research at Uniarts Helsinki in which she explores disorientation as a choreographic strategy. “Konturen” (2020) and “Yes Contours Time Disorientation xt”(2021) have put different performative structures into practice. “All late, all babe” will conclude the research in 2024.</ref> The task is simple: plan to rob a bank. While time and location situate the technique in the here and now, the task immediately opens up a space for collective planning fueled by the speculative energy of criminal conspiracy, making it speculative in its radical sense. It is a technique of future problem-solving rather than free-floating imagination. This combination of pragmatism and speculation is shared by many of the techniques included on ''nocturne''. They are pragmatic because they orient an action or a collective toward processes embedded in the here and now. They are speculative because they transform this process, feeding it into new situations, and thereby changing the collective as much as the situation itself. |

| . The task is simple: plan to rob a bank. While time and location situate the technique in the here and now, the task immediately opens up a space for collective planning fueled by the speculative energy of criminal conspiracy, making it speculative in its radical sense. It is a technique of future problem-solving rather than free-floating imagination. This combination of pragmatism and speculation is shared by many of the techniques included on ''nocturne''. They are pragmatic because they orient an action or a collective toward processes embedded in the here and now. They are speculative because they transform this process, feeding it into new situations, and thereby changing the collective as much as the situation itself.

| |

|

| |

|

| <br>

| | ==== Pragmatic Experimentation ==== |

|

| |

|

| ====Pragmatic Experimentation====

| |

| The techniques gathered at ''nocturne'' are not simply practice-based, but pragmatic in their philosophical sense. They take experience seriously as a starting point from which to work with theoretical concepts.<ref>John Dewey, ''Experience and Education'' (New York: Free Press, 2015); James, William. ''Essays in Radical Empiricism'' (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996); Whitehead, Alfred North. ''The Aims of Education and other Essays'' (New York: Free Press, 1967). </ref> Rather than just applying thinking to experience or experience to thinking, the relation between the two realms—theory and practice, thinking and experiencing—grounds every practice. This logic of co-composition shifts teaching from an act of mediating learning content, to a form of experimentation in which content and techniques are in constant dialogue and constantly rearranged, making the very distinctions between theory and practice, and concept and experience, even harder to maintain. When we think of pedagogical techniques and the activity of teaching, we do not limit it to the explanation of existing knowledge, but think of them as situations joint together by learning and experimentation, from which topics and techniques emerge and are experimented with. We consider learning in a broad and embodied sense, focusing on the art of creating situations from which something new can emerge. This is why we turn to those spaces where art, activism, and pedagogy are intertwined. | | The techniques gathered at ''nocturne'' are not simply practice-based, but pragmatic in their philosophical sense. They take experience seriously as a starting point from which to work with theoretical concepts.<ref>John Dewey, ''Experience and Education'' (New York: Free Press, 2015); James, William. ''Essays in Radical Empiricism'' (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996); Whitehead, Alfred North. ''The Aims of Education and other Essays'' (New York: Free Press, 1967). </ref> Rather than just applying thinking to experience or experience to thinking, the relation between the two realms—theory and practice, thinking and experiencing—grounds every practice. This logic of co-composition shifts teaching from an act of mediating learning content, to a form of experimentation in which content and techniques are in constant dialogue and constantly rearranged, making the very distinctions between theory and practice, and concept and experience, even harder to maintain. When we think of pedagogical techniques and the activity of teaching, we do not limit it to the explanation of existing knowledge, but think of them as situations joint together by learning and experimentation, from which topics and techniques emerge and are experimented with. We consider learning in a broad and embodied sense, focusing on the art of creating situations from which something new can emerge. This is why we turn to those spaces where art, activism, and pedagogy are intertwined. |

|

| |

|

| Line 54: |

Line 54: |

| <span class="page-break"> </span> | | <span class="page-break"> </span> |

|

| |

|

| ====Learning outside of the University==== | | ==== Learning outside of the University ==== |

| | |

| In recent years, non-academic learning formats have gained traction. They connect to the radical pedagogies of the 1970s and 1980s, to feminist and Black reading circles, to empowerment and consciousness raising, and to decolonial struggles in the Americas. They reference the pedagogical and therapeutic reforms of Fernand Oury and Aïda Vasques (1969), Paulo Freire (2018), bell hooks (1994), Félix Guattari (2015), and Fernand Deligny (2013). Movements influenced by these thinkers, teachers, artists, and political activists, have invented ways of learning that aim to make social, individual, and institutional transformation and change. | | In recent years, non-academic learning formats have gained traction. They connect to the radical pedagogies of the 1970s and 1980s, to feminist and Black reading circles, to empowerment and consciousness raising, and to decolonial struggles in the Americas. They reference the pedagogical and therapeutic reforms of Fernand Oury and Aïda Vasques (1969), Paulo Freire (2018), bell hooks (1994), Félix Guattari (2015), and Fernand Deligny (2013). Movements influenced by these thinkers, teachers, artists, and political activists, have invented ways of learning that aim to make social, individual, and institutional transformation and change. |

|

| |

|

| Line 65: |

Line 66: |

| Most aforementioned projects resort to the workshop as a format to facilitate their pedagogical and collective engagements. The workshop—be it a collective movement session, a hackathon, or a reading group—has developed out of the need to question the institution of the university. Especially nowadays, in times of increasingly modularized university education, workshops offer a way to collectively learn outside of established institutions.<ref>Anja Groten, “Workshop,” in ''Making Matters'', ed. Janneke Wesseling, Florian Cramer (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2022).</ref> These new sites and formats of “other knowledge”<ref>Kathrin Busch (Ed.), ''Anderes Wissen. Kunstformen der Theorie'' (Paderborn: Fink, 2016).</ref> often combine political intervention and collective organization. Many workshops establish situations that are open, while creating techniques that others can use in new and different contexts. | | Most aforementioned projects resort to the workshop as a format to facilitate their pedagogical and collective engagements. The workshop—be it a collective movement session, a hackathon, or a reading group—has developed out of the need to question the institution of the university. Especially nowadays, in times of increasingly modularized university education, workshops offer a way to collectively learn outside of established institutions.<ref>Anja Groten, “Workshop,” in ''Making Matters'', ed. Janneke Wesseling, Florian Cramer (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2022).</ref> These new sites and formats of “other knowledge”<ref>Kathrin Busch (Ed.), ''Anderes Wissen. Kunstformen der Theorie'' (Paderborn: Fink, 2016).</ref> often combine political intervention and collective organization. Many workshops establish situations that are open, while creating techniques that others can use in new and different contexts. |

|

| |

|

| <br>

| | ==== Technique and Institution ==== |

|

| |

|

| ====Technique and Institution====

| |

| On March 24, 1965, teachers and students across the U.S. left their scheduled seminars to spend the entire night in so-called “teach-ins,” debating U.S. policy on the Vietnam War. It was an act of public protest but more so—as Marshal Sahlins, one of the teachers involved noted—this inter-university, nationwide debate on the Vietnam War and U.S. Cold War politics produced “a genuine intellectual experience.” Sahlins elaborates, “for many the first they ever had on campus, perhaps because for the first time ''both'' teachers and students were discussing, seriously and with respect for each other’s opinions, something both were deeply interested in understanding.”<ref>Marshall Sahlins, ''Culture as Practice. Selected Essays'' (New York: Zone, 2000).</ref> This example shows that it is impossible for the university (the school, the museum, etc.) to capture the powerful act of teaching. In fact, Sahlins’ quote shows that, when teaching leaves the institution, it becomes an “intellectual experience” and a truly collective practice. Teach-ins opened up a space for other and new pedagogical techniques to emerge, techniques that were academic as much as activist. The simple shift of time and location produced other knowledges as much as collectivity. | | On March 24, 1965, teachers and students across the U.S. left their scheduled seminars to spend the entire night in so-called “teach-ins,” debating U.S. policy on the Vietnam War. It was an act of public protest but more so—as Marshal Sahlins, one of the teachers involved noted—this inter-university, nationwide debate on the Vietnam War and U.S. Cold War politics produced “a genuine intellectual experience.” Sahlins elaborates, “for many the first they ever had on campus, perhaps because for the first time ''both'' teachers and students were discussing, seriously and with respect for each other’s opinions, something both were deeply interested in understanding.”<ref>Marshall Sahlins, ''Culture as Practice. Selected Essays'' (New York: Zone, 2000).</ref> This example shows that it is impossible for the university (the school, the museum, etc.) to capture the powerful act of teaching. In fact, Sahlins’ quote shows that, when teaching leaves the institution, it becomes an “intellectual experience” and a truly collective practice. Teach-ins opened up a space for other and new pedagogical techniques to emerge, techniques that were academic as much as activist. The simple shift of time and location produced other knowledges as much as collectivity. |

|

| |

|

| As this example shows, techniques are more than an institutional intervention. As much as we find techniques at work in institutions they can also challenge and work against existing and emerging institutions. Techniques can transform power relations as well as ingrained patterns of acting and thinking. Techniques can render background structures conscious<ref>Kathie Sarachild, “Consciousness-Raising: A Radical Weapon.” in ''Feminist Revolution'', ed. by Redstockings (New York: Random House, 1978), 144–50.</ref> and create communities that oppose the processes of institutionalization and/or neoliberalization in the spirit of “lifelong learning.” Techniques are neither good or bad; institutional or revolutionary. They can always be hacked and used in different ways. It is, to use Alfred North Whitehead’s phrase, a question of “style,”<ref>Alfred North Whitehead, ''The Aims of Education and other Essays'' (New York: Free Press, 1967).</ref> how a technique is used determines its effects and impacts. In this sense, the style of experimentation can help to keep techniques in a process of continuous transformation. Changing and combining them with other techniques prevents their sedimentation into a rule or even law. It is sometimes necessary to continue a discussion beyond the timeframe of the seminar, for instance to allow an extensive debate on foreign policy, as in the case of the teach-ins. | | As this example shows, techniques are more than an institutional intervention. As much as we find techniques at work in institutions they can also challenge and work against existing and emerging institutions. Techniques can transform power relations as well as ingrained patterns of acting and thinking. Techniques can render background structures conscious<ref>Kathie Sarachild, “Consciousness-Raising: A Radical Weapon.” in ''Feminist Revolution'', ed. by Redstockings (New York: Random House, 1978), 144–50.</ref> and create communities that oppose the processes of institutionalization and/or neoliberalization in the spirit of “lifelong learning.” Techniques are neither good or bad; institutional or revolutionary. They can always be hacked and used in different ways. It is, to use Alfred North Whitehead’s phrase, a question of “style,”<ref>Alfred North Whitehead, ''The Aims of Education and other Essays'' (New York: Free Press, 1967).</ref> how a technique is used determines its effects and impacts. In this sense, the style of experimentation can help to keep techniques in a process of continuous transformation. Changing and combining them with other techniques prevents their sedimentation into a rule or even law. It is sometimes necessary to continue a discussion beyond the timeframe of the seminar, for instance to allow an extensive debate on foreign policy, as in the case of the teach-ins. |

|

| |

|

| <br> | | <span class="page-break"> </span> |

| | |

| | ==== Create access! ==== |

|

| |

|

| ====Create access!====

| |

| Teach-ins, workshops, and informal reading groups are modes of organizing learning beyond institutional frameworks, especially in countries with extremely high educational costs. Many of them aim to facilitate learning differently than universities—decolonized, democratized, and organized in solidary ways.<ref>Linda Tuhiwai Smith, ''Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples'', (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999).</ref> They create new collectives of thought, experience, and imagination. But even the simple act of reading together can lead to the exclusion of others and create hierarchies among its participants. Especially in collectives working across art, academia, and activism, the use of language and the distribution of who speaks when and for how long can institute and reinforce social power relations. How, then, can we create techniques that challenge these structures? How to invent formats that do not privilege certain (often academic) knowledge, but fosters the exchange between different forms and practices of knowledge? | | Teach-ins, workshops, and informal reading groups are modes of organizing learning beyond institutional frameworks, especially in countries with extremely high educational costs. Many of them aim to facilitate learning differently than universities—decolonized, democratized, and organized in solidary ways.<ref>Linda Tuhiwai Smith, ''Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples'', (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999).</ref> They create new collectives of thought, experience, and imagination. But even the simple act of reading together can lead to the exclusion of others and create hierarchies among its participants. Especially in collectives working across art, academia, and activism, the use of language and the distribution of who speaks when and for how long can institute and reinforce social power relations. How, then, can we create techniques that challenge these structures? How to invent formats that do not privilege certain (often academic) knowledge, but fosters the exchange between different forms and practices of knowledge? |

|

| |

|

| Line 83: |

Line 84: |

| Every pedagogical relation and every technique must therefore ask how it addresses exclusions based on gender, race, class, and dis_ability. The techniques assembled on the platform, ''nocturne,'' aim to counter subconscious exclusions and increase access on multiple levels. When sharing these techniques between the artistic, academic, and activist field, the question of access makes it important not to simply reproduce techniques in different settings. What creates access in one situation can be exclusionary in another one. Every technique needs to be tried out and developed in context-sensitive ways. | | Every pedagogical relation and every technique must therefore ask how it addresses exclusions based on gender, race, class, and dis_ability. The techniques assembled on the platform, ''nocturne,'' aim to counter subconscious exclusions and increase access on multiple levels. When sharing these techniques between the artistic, academic, and activist field, the question of access makes it important not to simply reproduce techniques in different settings. What creates access in one situation can be exclusionary in another one. Every technique needs to be tried out and developed in context-sensitive ways. |

|

| |

|

| <br>

| | ==== Make situations! ==== |

|

| |

|

| ====Make situations!====

| |

| We founded ''nocturne'' with an enthusiasm for learning and unlearning as critical and emancipative educational processes. In this context, we understand pedagogy primarily as a way of working with techniques to produce collective situations i.e., less autodidactic or individualistic learning. Here, we have primarily social and ecological processes in mind. Learning also means the experience of becoming different. This means not to be re-educated, but to create and encounter every new learning situation openly. | | We founded ''nocturne'' with an enthusiasm for learning and unlearning as critical and emancipative educational processes. In this context, we understand pedagogy primarily as a way of working with techniques to produce collective situations i.e., less autodidactic or individualistic learning. Here, we have primarily social and ecological processes in mind. Learning also means the experience of becoming different. This means not to be re-educated, but to create and encounter every new learning situation openly. |

|

| |

|

| Line 93: |

Line 93: |

|

| |

|

| In institutionalized higher education, pedagogy and didactics (as helpful as they can be in some cases) are often subordinated to questions of efficiency. We are urged to complete trainings in didactics to use our pedagogical methods purposefully, to give proper feedback, and to learn how to grade. While it is important to reflect on our power positions in educational contexts, we are rarely taught in these trainings about the activist teaching techniques of Black writers, workers struggle at the university, liberation pedagogies of the Americas, or the ways second-wave feminism organized learning and unlearning. With ''nocturne,'' we want to build on these traditions. | | In institutionalized higher education, pedagogy and didactics (as helpful as they can be in some cases) are often subordinated to questions of efficiency. We are urged to complete trainings in didactics to use our pedagogical methods purposefully, to give proper feedback, and to learn how to grade. While it is important to reflect on our power positions in educational contexts, we are rarely taught in these trainings about the activist teaching techniques of Black writers, workers struggle at the university, liberation pedagogies of the Americas, or the ways second-wave feminism organized learning and unlearning. With ''nocturne,'' we want to build on these traditions. |

| How to engage critically with the knowledge and affects produced by the university and other institutions is at the heart of the technique [[#Bodystrike|Bodystrike]] by the Feminist Health Care Research Group <ref>As artistic research project '''the Feminist Health Care Research Group''' (FHCRG) develops exhibitions, workshops and publishes zines. It aims to create space in which we can share vulnerability with each other, center (access) needs and break through the competitive mode of working in the arts. FHCRG questions the internalized, ableist concept of productivity that is rewarded in the art field.</ref>. Situated in the feminist tradition of self-organized health care, the technique offers way to work with the bodily and affective knowledge often sidelined in institutionalized processes of education. | | How to engage critically with the knowledge and affects produced by the university and other institutions is at the heart of the technique [[#Bodystrike|Bodystrike]] by the Feminist Health Care Research Group <ref>As artistic research project the Feminist Health Care Research Group (FHCRG) develops exhibitions, workshops and publishes zines. It aims to create space in which we can share vulnerability with each other, center (access) needs and break through the competitive mode of working in the arts. FHCRG questions the internalized, ableist concept of productivity that is rewarded in the art field.</ref>. Situated in the feminist tradition of self-organized health care, the technique offers way to work with the bodily and affective knowledge often sidelined in institutionalized processes of education. |

|

| |

|

| <br>

| | ==== Change the logistical university! ==== |

|

| |

|

| ====Change the logistical university!====

| |

| The logistical university is, as Moten and Harney put it, a university of debt: Debt through student loans and debt through credits to be earned.<ref>Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, T''he Undercommons. Fugitive Planning and Black Study''. (Wivenhoe u.a.: Minor Compositions, 2013), 61. </ref> What the students get for their debt is skill. Instead of facts, the university teaches skills that can be used elsewhere, and skills that travel and make the students travel through the market economy. This flow of skills renders the university and its students logistical. If we go back a few years, skills training did not begin as a logistical fantasy but as a critique of the accumulation of facts (as described by Paulo Freire in his “banking model“<ref>Paulo Freire, ''Pedagogy of the Oppressed'' (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018).</ref> method) and came with the promise of increased freedom. In recent decades, this development turned into a total obliviousness of knowledge only striving towards the teaching of skills to be applied in every situation at all times. If everything is transferable and applicable, any reference to the history, situation, and emancipatory politics of a technique is lost. When we engage in technique-sharing, we are not interested cookie-cutter applications that don’t engage with the situations from which the technique originates. We call for techniques that enable collectivity, solidarity, and openness. Elke Bippus and Monica Gaspar point out that the shift from content to competence (and thus to technique) can also bear the danger of feeding experimental ways of working known from art into all realms of economic production and education. Through collaborations between academia and the arts, precarization of both fields occurs, and this is highly based on self-exploitation. Creative techniques of the arts are fed into the field of capitalist labor, rehearsing its experimental character and accelerating precarious working conditions, which renders the arts as much as labor logistical.<ref>Bojana Kunst, ''Artist at Work, Proximity of Art and Capitalism'' (Winchester: Zero, 2015).</ref> Yet a critique of neoliberalism should not be conflated with a critique of creativity and experimentation as such. We need to address the critical qualities inherent in experimental techniques. In view of this development as well as the increasing institutionalization of artistic research in the sense of its scientification, we want to ask how techniques can produce solidary and critical forms of collective working. How can we rethink creative collaboration starting from the techniques at work in a situation? How can we foster speculative practices, which go beyond use of goal-oriented techniques? We hope that the exchange of techniques of learning and unlearning can lead to a revaluation of the concept of technique in a non-utilitarian manner. Techniques de-essentialize learning and knowledge through the focus on their processual and situated nature. Sharing these techniques must include engagement with the situations from which they originated. Like ''Everybody’s Toolbox''<ref>See http://www.everybodystoolbox.net </ref> proposes for the field of performance and dance, we think of techniques and instructions as open-source. They are open to hacking, modification, and speculative adaptation. Each technique Hon the platform is an invitation to its reader to document their own experiences, and share the techniques they work with. | | The logistical university is, as Moten and Harney put it, a university of debt: Debt through student loans and debt through credits to be earned.<ref>Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, T''he Undercommons. Fugitive Planning and Black Study''. (Wivenhoe u.a.: Minor Compositions, 2013), 61. </ref> What the students get for their debt is skill. Instead of facts, the university teaches skills that can be used elsewhere, and skills that travel and make the students travel through the market economy. This flow of skills renders the university and its students logistical. If we go back a few years, skills training did not begin as a logistical fantasy but as a critique of the accumulation of facts (as described by Paulo Freire in his “banking model“<ref>Paulo Freire, ''Pedagogy of the Oppressed'' (New York: Bloomsbury, 2018).</ref> method) and came with the promise of increased freedom. In recent decades, this development turned into a total obliviousness of knowledge only striving towards the teaching of skills to be applied in every situation at all times. If everything is transferable and applicable, any reference to the history, situation, and emancipatory politics of a technique is lost. When we engage in technique-sharing, we are not interested cookie-cutter applications that don’t engage with the situations from which the technique originates. We call for techniques that enable collectivity, solidarity, and openness. Elke Bippus and Monica Gaspar point out that the shift from content to competence (and thus to technique) can also bear the danger of feeding experimental ways of working known from art into all realms of economic production and education. Through collaborations between academia and the arts, precarization of both fields occurs, and this is highly based on self-exploitation. Creative techniques of the arts are fed into the field of capitalist labor, rehearsing its experimental character and accelerating precarious working conditions, which renders the arts as much as labor logistical.<ref>Bojana Kunst, ''Artist at Work, Proximity of Art and Capitalism'' (Winchester: Zero, 2015).</ref> Yet a critique of neoliberalism should not be conflated with a critique of creativity and experimentation as such. We need to address the critical qualities inherent in experimental techniques. In view of this development as well as the increasing institutionalization of artistic research in the sense of its scientification, we want to ask how techniques can produce solidary and critical forms of collective working. How can we rethink creative collaboration starting from the techniques at work in a situation? How can we foster speculative practices, which go beyond use of goal-oriented techniques? We hope that the exchange of techniques of learning and unlearning can lead to a revaluation of the concept of technique in a non-utilitarian manner. Techniques de-essentialize learning and knowledge through the focus on their processual and situated nature. Sharing these techniques must include engagement with the situations from which they originated. Like ''Everybody’s Toolbox''<ref>See http://www.everybodystoolbox.net </ref> proposes for the field of performance and dance, we think of techniques and instructions as open-source. They are open to hacking, modification, and speculative adaptation. Each technique Hon the platform is an invitation to its reader to document their own experiences, and share the techniques they work with. |

|

| |

|

| <small>'''Gerko Egert''' is a performance studies scholar. He is currently postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Applied Theatre Studies, Justus-Liebig-University, Giessen. He was visiting professor at HBK Braunschweig (2021) and Freie Universität, Berlin (2018). His research deals with experimental pedagogies and self-organized learning, philosophies and politics of movement, human and non-human choreographies, dance and performance, process philosophy and (speculative) pragmatism, especially in the work of Deleuze and Guattari. Gerko holds a PhD from Freie Universität Berlin. His Dissertation deals with the notion of touch in contemporary dance (published 2016 [Transcript Verlag], English translation 2020 [Routledge]). His current research focusses on a choreographic regime of power governing logistics, traffic, migration, (post-)colonialism among other scenarios of movement.

| |

|

| |

|

| In 2020 he founded together with '''Julia Bee''' the platform Nocturne.</small>

| | ::<small>'''Gerko Egert''' and '''Julia Bee''' founded the platform Nocturne in 2020. A platform aiming to provide a space and time for all the practices that emerge between institutions. A time in which the production and transmission of knowledge become collective practices, in which techniques of teaching become experimental procedures, and in which art and science do not enter into exchange but have already begun to work together in new ways.</small> |

| <br>

| |

|

| |

|

| </div class="block"> | | </div class="block"> |

| <span class="page-break"> </span> | | <span class="page-break"> </span> |

| | </div> |

| | |

| | <div class="article Give_and_Take layout-1" id="Give_and_Take"> |

| | |

| | <div class="hide-from-book scriptothek">

|

| | [[File:Give-and-take-Experimente-lernen.jpg|thumb|How-to "Give and Take" by Social Muscle Club," in ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook,'' edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).]]</div> |

|

| |

|

| ===Give and Take=== | | ===Give and Take=== |

| Line 121: |

Line 124: |

| * '''Step 7''': Keep going until you have worked with every piece of paper. Remember, not every wish has to be fulfilled. | | * '''Step 7''': Keep going until you have worked with every piece of paper. Remember, not every wish has to be fulfilled. |

|

| |

|

| | <small> |

| | ::''[https://nocturne-plattform.de/text/wie-den-sozialen-muskel-trainieren From: “Wie den sozialen Muskel trainieren” by Social Muscle Club'']</small> |

|

| |

|

| ''[https://nocturne-plattform.de/text/wie-den-sozialen-muskel-trainieren From: “Wie den sozialen Muskel trainieren” by Social Muscle Club'']]

| | </div class="block"> |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| <br> | | <span class="page-break"> </span> |

|

| |

|

| </div class="block"> | | <div class="article Bodystrike layout-1" id="Bodystrike"> |

|

| |

|

| <span class="page-break"> </span> | | <div class="hide-from-book scriptothek">

|

| | [[File:Body-Strike-Experimente-lernen-web.jpg|thumb|How-to "Bodystrike" by Feminist Health Care Research Group," in ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook,'' edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).]] |

| | [[File:Body-Strike-Experimente-lernen2.jpg|thumb|How-to "Bodystrike" by Feminist Health Care Research Group," in ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook,'' edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).]] |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| ===Bodystrike=== | | === Bodystrike === |

| <span class="author">Feminist Health Care Research Group</span> | | <span class="author">Feminist Health Care Research Group</span> |

|

| |

| <div class="block"> | | <div class="block"> |

|

| |

| * Find a quiet, comfortable place where you feel at ease. Prepare what you need for this exercise (pen and paper, timer). Make yourself comfortable. Breathe deeply and feel inside yourself. | | * Find a quiet, comfortable place where you feel at ease. Prepare what you need for this exercise (pen and paper, timer). Make yourself comfortable. Breathe deeply and feel inside yourself. |

| * Can you think of a physical reaction that you have learned is embarrassing / out of place in academic / artistic / institutional / school spaces, and that you should hide / be ashamed of, or discard? | | * Can you think of a physical reaction that you have learned is embarrassing / out of place in academic / artistic / institutional / school spaces, and that you should hide / be ashamed of, or discard? |

| Line 146: |

Line 153: |

| * Do you have, the other way around, an idea of the parts of you that rather form your “counter-knowing body?” What does it do, what does it communicate to you? What wishes does it have and to whom does it most likely make contact? | | * Do you have, the other way around, an idea of the parts of you that rather form your “counter-knowing body?” What does it do, what does it communicate to you? What wishes does it have and to whom does it most likely make contact? |

|

| |

|

| ::''[https://nocturne-plattform.de/text/korperstreik From: “Körperstreik” by Inga Zimprich (Feministische Gesundheitsrecherchegruppe)''] | | <small> |

| | ::''[https://nocturne-plattform.de/text/korperstreik From: “Körperstreik” by Inga Zimprich (Feministische Gesundheitsrecherchegruppe)'']</small> |

| | |

| | </div class="block"> |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| <br> | | <div class="article Conceptual_Speed_Dating layout-1" id="Conceptual_Speed_Dating"> |

|

| |

|

| </div class="block"> | | <div class="hide-from-book scriptothek">

|

| | [[File:Massumo-Experimente-lernen.jpg|thumb|How-to "Conceptual Speed Dating" by Brian Massumi," in ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook,'' edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).]] |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| ===Conceptual Speed Dating=== | | === Conceptual Speed Dating === |

| <span class="author">Brian Massumi</span> | | <span class="author">Brian Massumi</span> |

|

| |

|

| Line 171: |

Line 184: |

| # Bring the group back together and discuss in plenary session what was discovered about the minor concept and the text. | | # Bring the group back together and discuss in plenary session what was discovered about the minor concept and the text. |

|

| |

|

| | | <small> |

| ::''[http://openhumanitiespress.org/books/download/Massumi_2017_The-Principle-of-Unrest.pdf From: Brian Massumi, “Collective Expression. A Radical Pragmatics,” The Principle of Unrest (London: Open Humanities Press, 2017) 111-140, here: 111-112.]'' | | ::''[http://openhumanitiespress.org/books/download/Massumi_2017_The-Principle-of-Unrest.pdf From: Brian Massumi, “Collective Expression. A Radical Pragmatics,” The Principle of Unrest (London: Open Humanities Press, 2017) 111-140, here: 111-112.]'' |

| ::''German version: https://nocturne-plattform.de/text/kollektiver-ausdruck'' | | ::''German version: https://nocturne-plattform.de/text/kollektiver-ausdruck'' </small> |

| | |

| <br> | |

|

| |

|

| </div class="block"> | | </div class="block"> |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| <span class="page-break"> </span> | | <span class="page-break"> </span> |

|

| |

|

| ===The perfect robbery=== | | <div class="article The_perfect_robbery layout-1" id="The_perfect_robbery"> |

| | |

| | <div class="hide-from-book scriptothek">

|

| | [[File:Perfect-robbery-Experimente-lernen.jpg|thumb|How-to "The Perfect Robbery" by Juli Reinartz," in ''Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook,'' edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).]] |

| | </div> |

| | |

| | === The perfect robbery === |

| <span class="author">Juli Reinartz</span> | | <span class="author">Juli Reinartz</span> |

|

| |

|

| Line 210: |

Line 228: |

| * Day 5: Fourth mini-workshop (possible) and final performance | | * Day 5: Fourth mini-workshop (possible) and final performance |

|

| |

|

| | | <small> |

| [https://nocturne-plattform.de/text/der-perfekte-bankraub''From: “Der perfekte Bankraub” by Juli Reinartz''] | | ::[https://nocturne-plattform.de/text/der-perfekte-bankraub''From: “Der perfekte Bankraub” by Juli Reinartz'']</small> |

| <br> | |

|

| |

|

| </div class="block"> | | </div class="block"> |

| </div> | | </div> |