The not-yet: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

<span class="author">Frans-Willem Korsten</span> | <span class="author">Frans-Willem Korsten</span> | ||

<div class="no-indent | <div class="no-indent">''The not-yet'' is an intentionally anti-utopian attitude and mode of practice that anticipates future developments by realizing the potential in and of the ‘now’. As philosopher Hans Achterhuis noted, all utopian projects in a sense reject the present, or consider it as something to be destroyed in order to make way for the new.<ref>Hans Achterhuis, ''Utopie'' (Amsterdam: Ambo, 2006); ''Koning van Utopia: Nieuw licht op het utopisch denken'' (Rotterdam: Lemniscaat, 2016).</ref> The not-yet, instead, suggests that a future is already here, as a potential to be found and cared for.</div> | ||

It considers ‘an effort to collectively inhabit alternative imaginaries’. Instead of destroying the present, it aims to interrupt present conditions in order to ''learn''.<ref>Cf. Jeanne van Heeswijk, Maria Hlavajova and Rachael Rakes, eds., ''Toward the Not-yet: Art as Public Practice'' (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021), p. 14.</ref> | |||

If anything, the not-yet is a matter of a ‘transformative practice’. | It considers ‘an effort to collectively inhabit alternative imaginaries’. Instead of destroying the present, it aims to interrupt present conditions in order to ''learn''.<ref>Cf. Jeanne van Heeswijk, Maria Hlavajova and Rachael Rakes, eds., ''Toward the Not-yet: Art as Public Practice'' (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021), p. 14.</ref> If anything, the not-yet is a matter of <br>a ‘transformative practice’. | ||

===1. making a case for an alternative future=== | ===1. making a case for an alternative future=== | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

What potentials does a practice of the not-yet have? How can art’s critical potential be used to explore alternative possibilities in the present that materialize in a process of learning? The case presented here is a project that taught me a lot. It was called ''De vleesvrije stad'', or ''The Meat Free City'' and materialized in book form, and digitally on the website of Drawing the Times, a ‘<mark class="c2">platform</mark> for graphic journalism’ initiated by artist and graphic journalist Eva Hilhorst.<ref>See drawingthetimes.com/specials/the-meat-free-city/.</ref></div> | What potentials does a practice of the not-yet have? How can art’s critical potential be used to explore alternative possibilities in the present that materialize in a process of learning? The case presented here is a project that taught me a lot. It was called ''De vleesvrije stad'', or ''The Meat Free City'' and materialized in book form, and digitally on the website of Drawing the Times, a ‘<mark class="c2">platform</mark> for graphic journalism’ initiated by artist and graphic journalist Eva Hilhorst.<ref>See drawingthetimes.com/specials/the-meat-free-city/.</ref></div> | ||

[[File:The-Meat-Free-City- | [[File:The-Meat-Free-City-lighter-grey.jpg|thumb|Front cover of the book.]] | ||

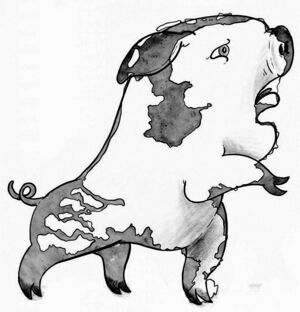

[[File:Meat Free City-Merel-Barends.jpg|thumb|One of the drawings by Merel Barends that shows the Netherlands in the shape of a pig, as alternative for the well-known Dutch Lion, symbol and icon for the nation; | [[File:Meat Free City-Merel-Barends.jpg|thumb|One of the drawings by Merel Barends that shows the Netherlands in the shape of a pig, as an alternative for the well-known Dutch Lion, symbol and icon for the nation; drawingthetimes.com.]] | ||

<span class="page-break"> </span> | <span class="page-break"> </span> | ||

''The Meat Free City'' project had its inspiring source in artist-designer Mark Schalken, and became a collective learning process in which all participants—graphic artists, scholars, designers, journalists—discovered potentials in a present that might form the beginnings of another future. Tellingly, the project was subtitled: ‘in ten years’. Yet this did not concern a blueprint for | ''The Meat Free City'' project had its inspiring source in artist-designer Mark Schalken, and became a collective learning process in which all participants—graphic artists, scholars, designers, journalists—discovered potentials in a present that might form the beginnings of another future. Tellingly, the project was subtitled: ‘in ten years’. Yet this did not concern a blueprint for a manageable plan with concrete steps to be taken. Rather, the participants were asked to think of possibilities existing in the present and how to hypothetically realize them—at a certain moment <br> | ||

a manageable plan with concrete steps to be taken. Rather, the participants were asked to think of possibilities existing in the present and how to hypothetically realize them—at a certain moment <br> | |||

in time, and within a time span of ten years. Each contribution focuses on an imaginary year, consequently, in which, for instance, schools host living animals and take them up in the curriculum; supermarkets no longer sell meat; municipal councils give one third of their seats to representatives of different groups of animals (<mark class="c2">zoöp</mark>). Thus, the idea was not just to imagine alternatives but to emphasize that these possibilities are already here, and could as well be realized now. | in time, and within a time span of ten years. Each contribution focuses on an imaginary year, consequently, in which, for instance, schools host living animals and take them up in the curriculum; supermarkets no longer sell meat; municipal councils give one third of their seats to representatives of different groups of animals (<mark class="c2">zoöp</mark>). Thus, the idea was not just to imagine alternatives but to emphasize that these possibilities are already here, and could as well be realized now. | ||

| Line 27: | Line 26: | ||

===3. the not-yet as a commitment to the present=== | ===3. the not-yet as a commitment to the present=== | ||

<div class="no-indent"> | <div class="no-indent"> | ||

When the Meat Free City collective accepted its task of making a work of art that would manifest an alternative reality, they decided to focus on the existing present. Obviously, this did not imply that they accepted everything the present had to offer. In fact, some of the contributors found out that the meat industry was even more abysmal than they had previously thought. For all participants, the project consisted of a collective pedagogical endeavour: a process of learning together, sharing knowledge, and considering different forms of imagining futures that would do justice to both the present and the future.</div> | When the Meat Free City collective accepted its task <br> | ||

of making a work of art that would manifest an alternative reality, they decided to focus on the existing present. Obviously, this did not imply that they accepted everything the present had to offer. In fact, some of the contributors found out that the meat industry was even more abysmal than they had previously thought. For all participants, the project consisted of a collective pedagogical endeavour: <br>a process of learning together, sharing knowledge, and considering different forms of imagining futures that would do justice to both the present and the future.</div> | |||

In this light, Donna Haraway’s ''A Cyborg Manifesto'' from 1985 still holds its force. In this manifesto, Haraway proposed an alternative future. The distinction between manifesto and utopia is pivotal here, in terms of function, style, and aim. The manifesto provoked its readers not so much to think of possible futures but to conceive of a better future as a possibility in the present. Like Marx and Engels, Haraway insisted ‘that possibilities for better worlds are born inside not outside the present relations of domination’.<ref>Kathi Weeks, ‘The Critical Manifesto: Marx and Engels, Haraway, and Utopian Politics’, ''Utopian Studies'' 24, no. 2 (2013), pp. 216–31, p. 225.</ref> This is why the potential of a collective that Haraway provocatively located in the cyborg is ‘fully implicated in the world’.<ref>Donna Haraway, ‘A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s’, ''Socialist Review'' 80 (1985), pp. 65–107, p. 95.</ref> Or, again, instead of fleeing towards the future on the basis of a fictive blueprint, real improvement is only possible if people consciously ‘inhabit the despised place’.<ref> | In this light, Donna Haraway’s ''A Cyborg Manifesto'' from 1985 still holds its force. In this manifesto, Haraway proposed an alternative future. The distinction between manifesto and utopia is pivotal here, in terms of function, style, and aim. The manifesto provoked its readers not so much to think of possible futures but to conceive of a better future as a possibility in the present. Like Marx and Engels, Haraway insisted ‘that possibilities for better worlds are born inside not outside the present relations of domination’.<ref>Kathi Weeks, ‘The Critical Manifesto: Marx and Engels, Haraway, and Utopian Politics’, ''Utopian Studies'' 24, no. 2 (2013), pp. 216–31, p. 225.</ref> This is why the potential of a collective that Haraway provocatively located in the cyborg is ‘fully implicated in the world’.<ref>Donna Haraway, ‘A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s’, ''Socialist Review'' 80 (1985), pp. 65–107, p. 95.</ref> Or, again, instead of fleeing towards the future on the basis of a fictive blueprint, real improvement is only possible if people consciously ‘inhabit the despised place’.<ref>Donna Haraway, ‘Nature, Politics, and Possibilities: <br> | ||

A Debate and Discussion with David Harvey and Donna Haraway’, ''Environment and Planning D: Society and Space'' 13 (1995), pp. 507–27, p. 514.</ref> Or, it is within an existing mode of production where the potential for a better world lingers, not as an ideal but within the material givens of that very world, and in the nigh inexhaustible potential embodied in life as ''zoë'' (<mark class="c2">zoöp</mark> and <mark class="c4">zoönomy</mark>). | |||

</ref> Or, it is within an existing mode of production where the potential for a better world lingers, not as an ideal but within the material givens of that very world, and in the nigh inexhaustible potential embodied in life as ''zoë'' (<mark class="c2">zoöp</mark> and <mark class="c4">zoönomy</mark>). | |||

<span class="page-break"> </span> | <span class="page-break"> </span> | ||

Latest revision as of 10:07, 12 April 2022

the not-yet

It considers ‘an effort to collectively inhabit alternative imaginaries’. Instead of destroying the present, it aims to interrupt present conditions in order to learn.[2] If anything, the not-yet is a matter of

a ‘transformative practice’.

1. making a case for an alternative future

The Meat Free City project had its inspiring source in artist-designer Mark Schalken, and became a collective learning process in which all participants—graphic artists, scholars, designers, journalists—discovered potentials in a present that might form the beginnings of another future. Tellingly, the project was subtitled: ‘in ten years’. Yet this did not concern a blueprint for a manageable plan with concrete steps to be taken. Rather, the participants were asked to think of possibilities existing in the present and how to hypothetically realize them—at a certain moment

in time, and within a time span of ten years. Each contribution focuses on an imaginary year, consequently, in which, for instance, schools host living animals and take them up in the curriculum; supermarkets no longer sell meat; municipal councils give one third of their seats to representatives of different groups of animals (zoöp). Thus, the idea was not just to imagine alternatives but to emphasize that these possibilities are already here, and could as well be realized now.

2. the principle of hope made real

In the project The Meat Free City, the hope for an alternative future found an anchor point in a collective process. This made the concept of hope materially real, through a mode of working together in commitment and solidarity. The project started in May 2020, smack in the middle of the Covid isolation, and would result in a publication of a Dutch book plus a digital version in English, in the spring of 2021. When publishers proved to be reluctant to bring out the book, or demanded the right to considerably alter its form and contents, the collective decided to raise money themselves, thus involving even more people but also safeguarding the artistic concept and process. The hope and reality of making this art piece in practice thus came to resonate with the hope and reality of an alternative future.

3. the not-yet as a commitment to the present

When the Meat Free City collective accepted its task

a process of learning together, sharing knowledge, and considering different forms of imagining futures that would do justice to both the present and the future.

In this light, Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto from 1985 still holds its force. In this manifesto, Haraway proposed an alternative future. The distinction between manifesto and utopia is pivotal here, in terms of function, style, and aim. The manifesto provoked its readers not so much to think of possible futures but to conceive of a better future as a possibility in the present. Like Marx and Engels, Haraway insisted ‘that possibilities for better worlds are born inside not outside the present relations of domination’.[4] This is why the potential of a collective that Haraway provocatively located in the cyborg is ‘fully implicated in the world’.[5] Or, again, instead of fleeing towards the future on the basis of a fictive blueprint, real improvement is only possible if people consciously ‘inhabit the despised place’.[6] Or, it is within an existing mode of production where the potential for a better world lingers, not as an ideal but within the material givens of that very world, and in the nigh inexhaustible potential embodied in life as zoë (zoöp and zoönomy).

4. conditions of change:

interruption or arranging coincidence

In recent years, a popular term in artistic circles was ‘intervention’. The term means, literally, that artists ‘come in-between’, perhaps in order to change a given situation. With the not-yet, however, the focus on both the collective process and the commitment to the present implies that intervention is only viable when artists do not already know what needs to be changed, but intervene to make change possible. Another term introduced in this context is ‘interruption’, a term that is of special relevance in the context of a capitalist system that can only function on the basis of constant movement; a movement that also blocks the emergence of alternatives. With respect to this, artist Jeanne van Heeswijk, in cooperation with BAK-Utrecht, shifted the emphasis from ‘emergency’ to ‘the emergent’ in the project ‘Trainings for the Not-yet’.[7] ‘The emergent’ aimed to underscore the possibilities in the now, or

the potential in the present, but also emphasized that the situation must be such that something can indeed emerge. The question then becomes what kinds of practices can make things emerge or coincide, in a process that time and time again asks participants to sense the implications of their practices or what the consequences of their actions may be. This is why the title of the project did not have ‘training’ in the title but ‘trainings’: practices. In this context, strategy has to give in to tactics. The tactic to make things coincide is

a tactic of arrangements, which can be transformative itself. Or, in working towards such coincidence, training for the not-yet will inevitably imply transforming one’s self.

- ↑ Hans Achterhuis, Utopie (Amsterdam: Ambo, 2006); Koning van Utopia: Nieuw licht op het utopisch denken (Rotterdam: Lemniscaat, 2016).

- ↑ Cf. Jeanne van Heeswijk, Maria Hlavajova and Rachael Rakes, eds., Toward the Not-yet: Art as Public Practice (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021), p. 14.

- ↑ See drawingthetimes.com/specials/the-meat-free-city/.

- ↑ Kathi Weeks, ‘The Critical Manifesto: Marx and Engels, Haraway, and Utopian Politics’, Utopian Studies 24, no. 2 (2013), pp. 216–31, p. 225.

- ↑ Donna Haraway, ‘A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s’, Socialist Review 80 (1985), pp. 65–107, p. 95.

- ↑ Donna Haraway, ‘Nature, Politics, and Possibilities:

A Debate and Discussion with David Harvey and Donna Haraway’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 13 (1995), pp. 507–27, p. 514. - ↑ See e-flux.com/announcements/266969/trainings-for-the-not-yet/.