|

|

| (92 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| <div class="article history-of-consensus layout-2"> | | <div class="article On_consensus,_in_two_parts layout-2 add-chaptertitle" id="On_consensus,_in_two_parts"> |

| | <div class="hide-from-website"> |

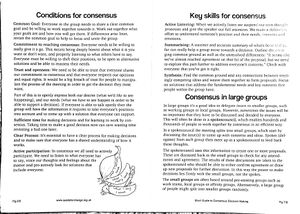

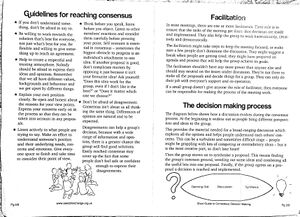

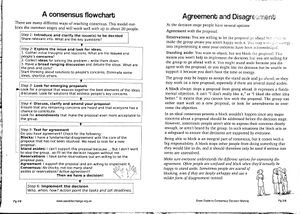

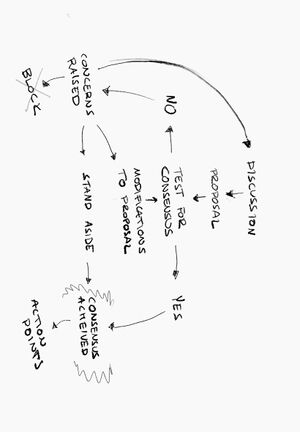

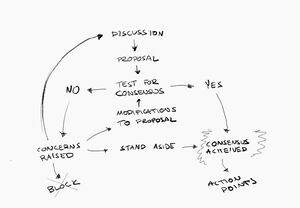

| | [[File:4-Consensus-diagram_print.jpg|thumb|class=title_image|A basic diagram for doing consensus]] |

| | </div> |

| | <div class="hide-from-book scriptothek"> |

|

| |

|

| [[File:Consensus1.jpg|thumb|Information about the flyer here .... ]] | | [[File:4-Consensusdiagram-web.jpg|thumb|A basic diagram for doing consensus]] |

|

| |

|

| === A history of consensus decision making ===

| | [[File:Consensus1.jpg|thumb|Collected hand-out from a workshop for art and design educators, reactivated during H&D Algorithmic Consensus Meetup, 2021. https://hackersanddesigners.nl/s/Events/p/H%26D_Meetup_1%3A_Algorithmic_Consensus |

| | Credits: Workshop: Angela Jerardi, 2019, Hand-out: Seeds for change https://seedsforchange.org.uk/]] |

|

| |

|

| <span class="author">Angela Jerardi</span>

| | [[File:Consensus2.jpeg|thumb|]] |

|

| |

|

| | [[File:Consensus3.jpeg|thumb|]] |

|

| |

|

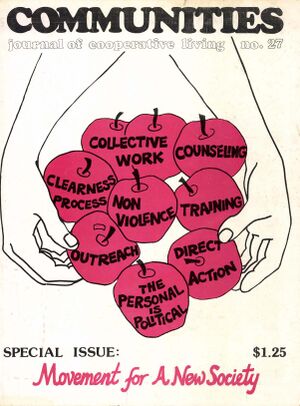

| But the aim of this talk is to speak about consensus as a method for decision making, but also more broadly as a means to structural non-hierarchical collaboration for a group to build community, identify conflict, and develop shared values and intentions. As a caveat to all of this, before I get into deep, many of these ideas have been close to my heart for a couple of decades, and much of the material I will speak of today I experienced in situ and intuitively learning along the way without too much, too much in the way of formal training. It was only much later that I became aware of how things I was involved in were actually a part of a larger story of anarchist and Quaker histories of the recent past. So this is something of a work in progress to synthesize my embodied experiences and understandings gained over the years with knowledge of the historical context and precedents that were shaping these very experiences. I did my bachelor study at one of the few remaining true Quaker universities in the United States, a place which is at once mostly secular and at the same time very much still attached to Quaker teachings. For example, virtually all the decisions that get made at the school are in fact made by a consensus decision making. Some years later, I moved to Philadelphia and became connected to intersecting circles there of radical Quakers, community activists and artists and designers. There are surely many genealogies of consensus, as one of the Quakers I will refer to today has said, quote, Consensus is a structural attempt to get equality to happen in decision making, unquote. Surely many people in many communities and many times have been concerned about how to make decisions in a group in a way that feels equal and fair. So in that sense, the notion of consensus must have many, many histories. Unsurprisingly, my reference points were consensus come from my geographical home in the Americas, from the traditions of the Religious Society of Friends, which is known as Quakers. Governance structure of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, sometimes known as the Iroquois Nation, which has existed and what is now known as Canada and the United States before such places existed, as well as the organizing and governing principles of the Zapatistas in Mexico. Today I'll be focusing on a specific strand of history that comes out of activist Quaker circles, primarily on the East Coast of the United States in the seventies and eighties. This is a little interlude into this. I was wanting to show some images, Quaker meeting houses. I think architecturally it's also interesting to think about how we can create spaces for equality or the sensation of potentially nurturing equality. I think Quaker Meetinghouse is a really beautiful example of that, and this one is one of my particular favorites. It's in Philadelphia, the Chestnut Hill neighborhood. And James Turrell, the artist, New Zealand artist that you've heard of, is also a practicing Quaker. And he installed this space in this building so that you can also experience this art at the same time as Think about God. So, bakers. Who are they? What's their story? Quakerism began in the mid 17th century in England. It was part of the larger situation of dissenting Protestants, people that were not happy with the way Protestantism was being interpreted at the time, and is definitely related also to the English Civil War, which was happening in the mid 17th century. The Centrepoint of Quaker belief is on the notion of testimonies finding and answering that which is of God in everyone. So the belief that everyone has God in them and testimonies are an expression to the commitment to put these beliefs, this belief of having God in everyone into practice. Quaker testimonies have changed very little over the centuries and centre on some key concepts piece. So in that case, peacemaking, but also nonviolence, quality and therefore seeking justice, integrity, consistency and word and indeed community. So living in fellowship and being concerned about how you build community with others simplicity, spirit, lead, restraint. There's many interpretations of that which maybe more traditionally would have been to do with dress or habits. But today, I think, is seen in many different ways, such as like concern with how you would use resources or how you consume, also how you interact with others. Yeah, there is enough for everyone's need, but not for everyone's greed is a quote from Gandhi that is sometimes referred to. And then lastly, stewardship. Care for the Earth and its inhabitants. Perhaps counterintuitively, the use of consensus in most radical political organizations has religious roots in the beliefs and practices of Quakers. To understand this, you need to know that Quakers believe it is possible for God to speak to all believers directly that a sacred presence exists as an inner light within everyone, thus removing the need for clergy to interpret God's will. Traditionally, Quakers worship by sitting together silently until members of the congregation feel moved, ostensibly by God, to share a message with the community as very finely portrayed in Fleabag. Quaker's model meetings to handle business and social and political initiatives in the same way based on the same approach. Participants take turns expressing ideas. They refrained generally from responding directly, but more in a way of trying to build ideas together. Instead, discussion continues until there is a sense that all participants share a general agreement about what is to be done. Or can at least accept the position of their compatriots. Or come to a primary decision and can live with that. Through this process, those processes can be time consuming. Quakers are invested in it because they believe the process of reaching consensus is inseparable from the presence of the divine. As historian April Hare has written, quote, For over 300 years, the members of the Society of Friends have been making group decisions without voting. Their method is to find a sense of the meeting, which represents a consensus of those involved. Ideally, this consensus is not simply unanimity or an opinion on which all members happen to agree, but an actual unity, a higher truth which grows from the consideration of divergent opinions and unites them all. So from here, I'll shift gears a little bit and bring us forward into the seventies. And I wanted to talk specifically about this group that I am very fascinated by called Movement for a New Society. They self-identified as a feminist, radical, non-violent organization. They were active from 1971 until 1988 in the United States. They had chapters in about a dozen or so cities and towns, towns throughout the United States. The hub was in Philadelphia. The ideas that they developed connected with many other activist struggles at the time. So for example, with feminist feminist liberation, also early ecology struggles and anti-nuke activism. A core part of the group's ethos with sharing knowledge, doing trainings and also working directly on themselves. So being concerned about doing anti oppression trainings with themselves, co counseling and something that they termed macro analysis seminars. The purpose of those seminars was to study together, but also to recognize their own internalized racism, sexism, homophobia and classism. So they could figure out how to identify their own problems while also trying to do movement work, macro analysis seminars or long term collaborative student groups modeled on the study group. Sorry, not student groups study or study groups modeled on the popular education efforts, both from the civil rights movement, but also on the ideas of fair. And I thought it would be nice to sort of give some context for a movement for new society to share. Also about this precursor, this group that existed shortly before them. They were founded in 1966, a radical Quaker action group they were called. And a radical Quaker action group grew out of the radical and leftist Quaker concerns about wars and violence in the world. And one of the interesting things that they did was that they were really interested in doing creative, direct, nonviolent campaigns to talk about how how to do peace or how to to protest violence. And so one of the ways that they decided to do that was through purchasing boats and then shipping materials of importance. So in this case, like antimalarials bacterias, antibacterials and bandages to Hiroshima. And then in another case, they did something similar in Vietnam with their boat. And the boat is called the Phoenix. And the idea behind this was really to try to do direct nonviolent action in campaigns, also, because they felt that nonviolent campaigns and activist work stemmed for them for the belief that war is inherent to capitalism and that social inequality in and of itself is a form of violence maintained by the threat of state violence. So therefore, to work for peace and equality or to abide by the Quaker testimonies that I just spoke about, in their words, one must be a social revolutionary. There was no other choice. Yeah, I find these examples quite interesting, but maybe it seems quite. Out of time now to think about. But one of the things that they are really interested in that I find intriguing is this notion of image defeat. And so and or maybe actually not out of time, but that it's now just sort of so commonplace. We don't think of it in the same way, but for them, they were really interested in basically creating like kind of creative, speculative moments where they would get a lot of media coverage and it would potentially replace other things that were happening. So for example, when this boat, the Phoenix, went to Vietnam and it ended up on the front page of many newspapers, and they saw this as something that they called an image defeat of the US government, because instead of the war being on the front page, it was about radical Quakers going.

| | [[File:Consensus4.jpeg|thumb|]] |

|

| |

|

| | [[File:2a-communities-no-27Page01.jpg|thumb|Cover of 'Communities: Journal of Cooperative Living,' July/August 1977. https://wiki2print.hackersanddesigners.nl/wiki/mediawiki/images/e/ec/2a-communities-no-27.pdf]] |

|

| |

|

| Vietnam with food and supplies on this boat. The Movement for New Societies. Introductory pamphlets are the first sort of public text that they produced. Declared its opposition to quote, traditional forms of organization from the multinational corporation to the PTA acronym for Parent Teacher Association. For they exhibit the sexism and authoritarianism we seek to supplant. Thus, the movement we build must be egalitarian and non centralized. Yeah. I'm just generally very fascinated by this group, so I could go on and on, but I will try to keep it short. There's a number of things I find really incredible. They were really concerned about combining external work with internal work. So they in one way, they wanted to make sure that they were thinking about how they lived. Many of them live collectively. They actually built a land trust in West Philadelphia, where they owned co owned houses together and they wanted to live more in accord with the world that they wanted to see. So this is, to me, one of the really crucial precursors of the idea that's now, I think, quite common in anarchist circles, pre figurative politics, the pre figurative modeling. So they were building food co-ops, creating reading spaces. They also create a publisher printer in Philadelphia. This was to create jobs for people, but also to make sure, for example, that low quality organic food was available to people in the neighborhood. As they said, your means must be in line with the end goal that you seek to create. And another thing that they another quote from them. We need to simplify and organize our life together so that there is time for the confrontations that are needed if the old order is going to fall. So creating the social relations and institutions that we want to know, that we want to exist right here, right now, rather than waiting for after the revolution for them to come into being. So the thing I wanted to bring up also as a sort of important history or genealogy of consensus is to ask and it's a bit weird to do this without an audience because I'd love to chat with you all about it. But to me, I sort of came into consensus both through studying at a Quaker university, but also from being involved in activist and art related activities. And it felt to me that consensus building was just de rigueur, commonplace in a lot of political and social activist work that I was connected to or many communities that I heard about. It certainly seems that this is probably the case now, but I'm very curious to hear about it from people here today. But I know, for example, Greenpeace uses it or Extinction Rebellion. It was used during Occupy. So many people are familiar with it in one way or another. And so I wanted to bring up that this concept of consensus building and many other adjacent methods, such as affinity groups and spoke councils, came from the influence of the movement for a new society, as far as I understand it. And another activist group, Quaker Ties the Clamshell Alliance. The Clamshell Alliance, which movement for a new society was a part of formed to protest the proposed SEABROOK Nuclear Power Plant plant that was planned for the northeast of the US. It's non-violent. Occupation of the power plant in 1977 was hugely successful, garnering lots of media attention and 1400 people were arrested. Interestingly, also, I assume that they plan it this way on purpose. They occupied it on April 30th and the arrest happened on May 1st. So on International Workers Day. So the 1400 people that were arrested en masse together were held in makeshift jails in National Guard armories for two weeks because they collectively chose to refuse bail. What happened next was in many ways or in some ways, at least in my opinion, more significant than the protest itself or the sit in itself. Movement for New Society was influential along with other people in in the Clamshell Alliance and organizing within the Armory, such that for the two weeks that the protesters were held there, the time was spent holding trainings, using spoke councils to facilitate collective decision making on legal strategy hosting, dance parties, skill sharing, other celebrations such that crazily enough, the detention actually became a time of networking and empowerment for the 1400 people that were there. And I think that, in my opinion, this really leads to how this notion of consensus building and other related methods like spokes council. My suspicion is that this is how it became so popular or no.

| | [[File:2a-communities-no-27Page02.jpg|thumb|Pages of 'Communities: Journal of Cooperative Living,' July/August 1977. https://wiki2print.hackersanddesigners.nl/wiki/mediawiki/images/e/ec/2a-communities-no-27.pdf]] |

|

| |

|

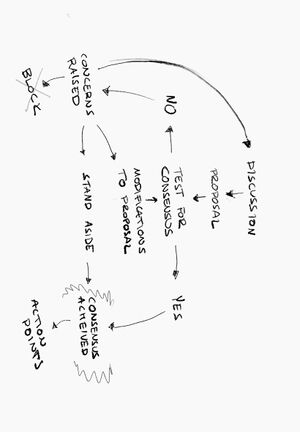

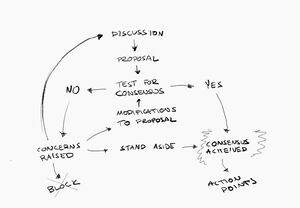

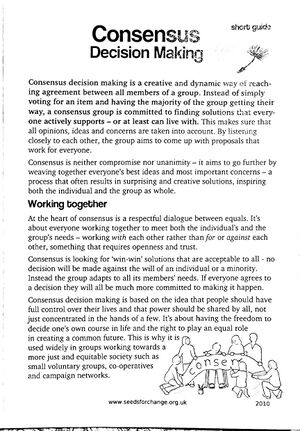

| ''Speaker 1:'' That. So just thought it'd be nice to share some images of what things were looking like at that time. Okay, so what is consensus? Consensus is a collective, creative, problem solving process created with or through. And this is my definition receptive, receptive and empathic listening. Digestion and connecting. So finding commonalities and threads between ideas and concerns, and importantly, also noting differences in dissonance. And synthesizing and translating. So what I mean by that is voicing propositions that bring together divergent ideas, concerns and approaches. So to me, this is the core of consensus. It's my version. So you can take it or leave it. But I see it as a collective creative process and that there are certain things that you need as a from the outset to be able to do it. Very important to be able to listen, very important to be able to practice digesting and connecting. So finding connections and then also to synthesizing and verbalizing these connections that you find. This is a sort of diagram of what the consensus process can look like. It starts on the top with discussion. Sometimes also people will make a diagram that shows sort of a point that opens out into a bigger thing and then closes back down to a point. So in this case, the idea is that you start with discussion. It opens into a much broader conversation. Eventually, through the discussion, proposals will end up on the table. Hopefully one, but maybe multiple. Then what you do is you test for consensus. And as you can see, when you test for consensus, you would be asking the room, how are people feeling about this proposal? Yes, well, great consensus achieved. Bring about a boom. Everybody go home. Well, probably not. So then you go to no. And then that's where a really important thing happens, which is that concerns get raised. And sometimes in my experience, if the discussion is really rich and people are very open in the discussion, then concerns will already have been raised when the proposal gets made. Sometimes, though, maybe something wasn't thought of until later. You just never know or there's really big issues at play that concern needs to get raised. Then you kind of go back to the discussion phase and you're making modifications to the proposal you're brainstorming together. Is there a way that we can still take the initial proposal and rework it, or does it need to be thrown out and a new proposal made? If so, and the modifications are made, then of course you would test for consensus again. If not, then you end up in a difficult situation for sure. And this is maybe why some people are quite critical of consensus. But I think that that's not necessarily a reason to not do it. And what I find useful is that there are very if you have if you have the benefit of maybe being trained or experiencing consensus, consensus in action with people that have done it, you see the options that are available to you, which are to stand aside or to block when you are not happy with the proposal and to stand aside, as maybe it sounds like ostensibly you say, I understand why people are excited about this proposal or why a lot of it makes sense to the broad group. And therefore I will stand aside and stand down. And what, of course, can be an issue and consensus processes, but I have really appreciated when people use it judiciously, is the block, which is that basically it is possible for any one person in the group to say, I will not stand by this proposal and therefore it will get stuck and would have to go back through process. There's definitely many modifications that have been made of how to think about this and that. You can make it so that maybe multiple people have to block in order for the block to be held or to not allow people to block unless they've been involved with the whole process. So it's like it's not a hard and fast rule. And I think that's what's also to me quite interesting about consensus is it has. It's more of a meta philosophy than it is a strict rule of how to do it. It's more about how do you approach the process of assuming that we are all in a conversation in good faith with one another and are interested in trying to find a solution together? And that creates, I think, a different dynamic in a group. So here I wanted to bring up the conditions for consensus. These are really important to think through. So, for example, a common goal. Everyone in the group needs to share a clear, common goal or goals and be willing to work together towards it. It's important to work out together what your goals are and how you will get there if differences arrive later. Revisit the common goal to help it to help focus and unite the group. Similarly to me, one of the most important ones is this question of trust and openness, or what I like to call arriving in good faith. We need to be able to trust that everyone arrives with the intention of working together, that everyone respects our opinions and equal rights. It would be a big breach of trust for people to manipulate the process of the meeting in order to get the decision they most want. And this, I think, is really crucial. Part of this is to openly express our desires so what we would like, but also our needs, what we have to have happen in order to be able to live with a decision. And that can be quite vulnerable, actually, in groups. But I think it's very empowering also for a group because it means that, yeah, we're sort of reaching towards understanding one another and maybe, maybe it can be quite difficult and sometimes awkward, but we then understand why something is needed by someone, and that maybe then makes it more possible to understand how modifications might be necessary to meet that need. If everyone is able to talk openly, then the group will have the information it requires to take everyone's positions into account and to come up with a solution that everyone can support. Obviously, or I would hope it's obvious, maybe not that a crucial condition is a commitment to reaching consensus. So if people enter the space without that kind of commitment, then most likely you will not get there. I can't imagine how you would really. So everyone needs to be really willing to give it a go. Maybe if it's not a methodology that you experienced before, it might be hard to be open to it. And that would be kind of to me, a very important condition to work with is to really create a space where people agree or have an intention when they arrive. It means being deeply honest about what you do and don't want, but also really important to listen, and maybe most importantly, to realize that you yourself can shift positions and opinions through listening and through thinking with others. As Anya sort of noted in the beginning, sufficient time is a really important issue for consensus. It's maybe its most famous problem. I have experienced that in my life, but I've also experienced many very well run consensus processes that were very satisfying and enjoyable to be a part of. But I've also been in ones that were very difficult, very frustrating and way, way, way too long. I think another part of that that's really important is good quality facilitation, so that people are really understanding what's expected and when and being aware of what people can and can't give in terms of time and energy. That's maybe something we could talk about more, but it is something to take into account, especially thinking about people's different situations, different backgrounds. You could say that time is a privilege that not everyone has. Clear process that kind of comes also to facilitation planning. So just that it's super crucial to have a clear process for making decisions, making sure that everybody knows what's up, what's the plan? When do you need to be aware? Yeah, maybe that goes without saying, but to have a clear process and to have it stated from the outset. So the expectations are. Yeah. Close to reality. That's always a good thing. And lastly, active participation. So in consensus, we all need to actively participate. We need to listen to what everyone has to say. Voice our thoughts and feelings about the matter and proactively look for solutions that include everyone. That's not always easy, but I think it's really important and interesting to think about that challenge or to sort of lean into that challenge of how do you. Potentially rethink something that you thought you needed to address someone else's need, for example. I thought I would also share this little sort of infographic that was made by Adam Clifford as part of I think this was made actually originally for like a booklet for Occupy the Occupy movement in New York. Well, everywhere. But I think this one was made for the New York one and this was another or it's a common idea, but different, slightly different versions, I think, in slightly different communities. But to use hand signals, because consensus can be time consuming, it can be very helpful to have hand signals to indicate things so that things don't need to be verbalized. Therefore, you can save valuable time by indicating something with your hands. Another one that I've used in meetings is this like five finger system, which is sort of like a straw poll. And that can be that people can indicate if they strongly agree with something or strongly disagree with something. Oh, shoot, I'm not on the screen. This doesn't make sense. But you do. Okay, sorry. I'm forgetting where I am. So? So, yeah. A five finger system where you could be like, strongly agree or strongly disagree. And then there's a lot of range between. So this can be really helpful in a meeting where like if you do this, that's something that you could also do this or you could also do this. And that way you can kind of see a range in the room, especially if it's a larger group. This can sometimes be helpful. So the hand signals here are like agree and unsure and disagree and block and point of process and point of information. And I have a question and wrap it up. And yeah, I think all of us mostly probably would make sense. Point of information is like that. You would be able to interrupt somebody with a quick point like, Oh, actually, I heard from Sally that that's not possible, so let's not waste time talking about it. So that can be really helpful because sometimes just you have a bit of information that others don't have when a process is more an interjection. So those are both sort of interjection interruption modes and quite a process is I thought we were doing this in a different way. Can somebody please clarify the process? Because I'm now thinking that this isn't what we're meant to be doing right now. It can also be very helpful. I think hopefully the rest kind of speak for themselves. So what is consensus good for? I think it's good for lots of things. But maybe because I'm a big proponent of consensus movement for a new society, members used it for decades. And to me, that is a good like a helpful experiment in thinking about what it is and isn't good for. They found it was helpful, and specifically three ways that I find very important to think with. I think there's also other ways that it can be helpful, but in these three ways I think it's especially helpful. So they spoke to how it helps empower more reserved and less experienced participants, creating a more even field for all. So this can be really helpful if you're working with a heterogeneous group who maybe some people have a lot of experience with that organization and some people have just joined. How can you create a space that really ensures that all voices are counted equally? Similarly, it can keep in check the sometimes competing egos in an organization or group. So one of the things I was reading about or thinking about before this talk is something that movement for new society identified of overtly leadership. So when a group has an overt leader and therefore it's known that that person is leading and covert leadership and how this can often happen in non-hierarchical groups, that there are actually covert leaders in the group and they're not stating their leadership role. And this can be quite tricky, obviously. And so one of the things I think consensus can do well is to sort of force everybody to actually be on the same level force that sounds kind of negative and fine, but to place everybody on the same level and to not allow different egos to take over too much in the process. It also would be interesting to think about how to use this kind of process. And I mean, I don't think that you certainly can use a consensus based process with a leader organization. It's not like consensus can't work in hierarchical organizations. I think it would also be equally valuable there, and I think there's lots of great arguments also for organizations that are working on hierarchy. Also identify why in some circumstances it's important to have leaders working on specific things or maybe rotating leadership or these kinds of things. But that's maybe a bigger conversation for another day. And then the last thing, which to me is the most important or one of the most important things about consensus, is the way in which it takes time to have a deeply considered conversation and to really invest time and energy into. That means that you're taking whatever the topic or goal is seriously and you're going to sit with it. And that's, of course, kind of a gift of time for all of us to do. But when doing that, it can really create a circumstance where a group can, as they say here, especially in a group's early state, where it is searching for new ideas and building unity, I think it can also be at points not just when a group is new, but especially when a group is reflecting or it's meeting a new transition. It can be really, really helpful. I mean, in a way, it's sort of similar to like a strategic planning process or other kinds of reflective activities that groups can do to really sit down and think about what issues are at play and make a space construct a space in a time where people can be forthright and vulnerable about what they're wanting and needing from the group. I think this is one of the things that consensus can do really well. Importantly, when to not use consensus. When there are no good choices. So this might seem really obvious, but there are some times that people will plan very long consensus processes realizing that there is not a good choice. So this is actually kind of a lot of this is borrowed from Starhawk, a very smart and super interesting activist in the States. And she says consensus process can help a group find the best possible solution to a problem, but is not an effective way to make an either or choice between evils. And she says if the group has to choose between being shot and hung, then flip a coin, obviously. So if a group gets stuck in a process, if your group or you are getting stuck, it can be very useful to think, am I blocked? Because there's actually like a problem that we need to chew on or am I blocked because the situation itself is intolerable and there is not a solution and therefore maybe the best option would be to refuse the decision. There is no decision. I think that's a really important one to think with. Maybe more obvious when it's an emergency consensus does not work well in emergencies. If you need to decide about something very, very quickly, I would suggest nominating a leader to make a decision on the group's behalf. Also maybe an obvious one when the decision is trivial. So you do not need to sit and have a consensus process to decide if the lunch break will be 45 minutes or one and one hour. You can just allow somebody to make this decision for you. It might sound obvious, but actually I think some groups get so invested into consensus and working non hierarchically that they feel that everything has to be agreed upon by everyone. This is not practical. It can be maybe really useful to think about what decisions the group needs to have everyone's agreement to and which ones people can take on their own have autonomy to make those decisions. When a group has insufficient information, this might also seem obvious, but can actually also very frequently happen. We just don't know enough about the circumstances, so therefore we can't make a good decision in that case, as this text says, send out scouts. Yeah. Ask What do we need to solve this problem? And what what can what information can we get to help us figure it out? Um. Yeah. A few more. When there is no group in mind. So a group thinking process cannot work unless the group is cohesive enough to generate shared attitudes and perceptions. This can be quite tricky and maybe this would be really interesting for thinking about the exercise today. One of the goals, I guess, of many of what I think a lot of what we're busy with in the world, people I know are busy with in the world right now is to think about how do we deal with heterogeneity and difference and how do we make groups and make it possible for groups to speak with one another? This is a really huge question and not an easy one. I think for consensus to work in the way that I'm describing it today in person and working through a process with a group of people, you do need to create a kind of cohesion. It could be through many ways and it could be a temporary it could be a temporary group that exists and it would shift over time. But there would be need to be another concept of community agreements, which is similar, I think in some ways to the code of conduct that was discussed at the beginning is how do you make an agreement when you come to the table with one another of how you will and won't work together? So this can be over a longer term, but it could also be for a specific meeting or project. So but to ask yourself, how do we generate shared attitudes and perceptions? How do we agree on the way we will work together, or what kinds of questions we're going to ask of each other? How much will we demand of one another when deep divisions exist within groups bonding over individual desires, consensus can become an exercise of frustration. Maybe many of us know that's whether or not we've done formal consensus processes or not can be very frustrating when you realize that your desires and those in the group are so opposed to one another that there's maybe no way to resolve it. Maybe most importantly and most interesting to me would be when a group isn't willing or able to grow. It might sound. I think actually sometimes groups come to this point where they're not willing to grow any longer and therefore they're hitting points where the what consensus is asking of them isn't possible. So how many groups are generally capable of sort of thinking about these kinds of questions of how to embody quality their work? Yeah. And maybe also it's helpful for us to think of a consensus not as necessarily a thing that we do in the room on 2:00 on the Thursday, but an overarching process that we try to work towards and maybe are always failing at. So maybe it's something that we're kind of practicing at and accepting that it will never we'll never reach that point. And that's okay. It's more about a practicing. Lastly, sometimes people try to make consensus processes when there's actually no decision to take. That might sound obvious, but what I mean is sometimes groups will think that we really have to decide on something together as a group, but in fact, it's not really necessary for everybody to be on board. It would be possible for people to say, Actually, I'm going to go to that thing on my own. And it's not really necessary that the group buys into this plan that I have. Sometimes things can get muddled when we're working between individual projects and collective projects about what is sort of my personal responsibility and what is the group responsibility. And this.

| | [[File:2a-communities-no-27Page03.jpg|thumb|]] |

|

| |

|

| Part of it is maybe about figuring out expectations and making clear for ourselves what we want to be ours and what we want to be the groups or vice versa. Hopefully that makes sense. Yeah, I think that's sort of coming to the end of what I prepared. I have one last thing that I wanted to say, which is a whole nother conversation that I would love to research and write and talk about to anybody. Be interested to do that with me at some point. But why is your consensus process so damned white? It's been an issue, I would say, within the US circles of people that have been involved with the building of consensus process proliferation. Definitely within activists and art circles that I've been involved with. On one hand, I think it's much more complicated. I'd like to believe it's much more complicated to kind of situate that history of consensus into some of the histories that I discussed today. And I think there's something to I mean, contextualization, I feel, is important for thinking about how for the Quakers, it came specifically out of these testimonies and the way that they think about being spiritual and how important that is to that trajectory of religion. And at the same time, to recognize that, yes, it was very much coming from specific groups in that religion who were primarily white and middle class Americans. And so in that sense, you could say that consensus, as the way I describe it today, is something like from white culture. And at the same time, it certainly has connections and many histories and genealogies that come from other cultures. As I pointed out that how to Shoni and Zapatistas are very well known for their use of consensus. So I think it's worthy of being discussed. But also something important to talk about, which I've definitely been thinking about, is like maybe white can become a stand also for the question of privilege, which is like who has the privilege of time and energy to be able to work this way? If you're working three jobs, obviously you do not have time to sit in a four hour meeting. So that's something important for us to think about. And I don't have any easy answers, but it's definitely something I am really interested in because I really believe in consensus as a process of working, but also understand that it asks a lot of the people that are involved.

| | [[File:2a-communities-no-27Page04.jpg|thumb|]] |

|

| |

|

| | [[File:2a-communities-no-27Page05.jpg|thumb|]] |

| |

</div> |

|

| |

|

| | === On consensus, in two parts === |

| | <span class="author">Angela Jerardi</span> <br> |

| | ''The following material was originally collected and delivered as a talk, in an effort to do two things: 1) To tell the story of one of the origins of consensus and its role in decision-making through a situated approach, and 2) To share some practical nuts and bolts learnings on how consensus can be put into practice.'' |

| | |

| | ==== Part I: A short and partial history of one genealogy of consensus<ref>Throughout my late teens and early twenties I studied at a Quaker university and became increasingly interested in the Religious Society of Friends, as it is also known. I became connected to some Quaker circles in Philadelphia, and at one point lived in a house connected to the group ''Movement for a New Society''. It feels useful to share this here since my proximity and participation in these communities has deeply shaped me and my understanding of doing democracy.</ref>==== |

| | |

| | <blockquote>“We are so accustomed to majority rule as a necessary part of democracy that it is difficult to imagine any democratic system working without it. It is true that it is better to count heads than to break them… but the party system has proved very far from providing the ideal democracies of people’s dreams.”<ref>This quote comes from the 1945 essay “Sociocracy: Democracy as It Might Be” by Dutch educator and pacifist Kees Boeke. While doing this research I’ve been living in Amsterdam, so it felt important to ground my study by learning about Quaker developments here in the Netherlands. Kees Boeke grew up in Alkmaar, Netherlands, in a Mennonite Dutch Reformed household but later converted to Quakerism. A passionate reformer of education, he founded a school in Bilthoven, and developed a form of critical pedagogy based on Quaker ideas and created the concept known as sociocracy, the theory that all individuals should have a role in decision making. Essay accessed at: https://www.sociocracy.info/sociocracy-democracy-kees-boeke</ref></blockquote> |

| | |

| | This quote takes us slightly astray from where I want to go, but it gets us thinking along a helpful track. For one, why is it so challenging to imagine democracy without majority rule? For many of us, the image of democracy is limited to its representational forms—someone else acting on our behalf, our direct role relegated to that of a voter, and the often entrenched non-action, bickering, and corruption endemic within systems built on political parties and coalition governments. The aim of this text is to think democracy otherwise, proposing consensus as a means for doing democracy. [[#WINWIN|Consensus]] is understood primarily as a method for decision-making, but I want to argue that it also offers a way of organizing methods of thinking and processing in groups that can create infrastructure to develop non-hierarchical collaborations, build community, identify conflict, and gestate shared values and intentions. As community-organizer and facilitator George Lakey puts it, “Consensus is a structural attempt to get equality to happen in decision making.”<ref>Andy Cornell and Andrew Willis-Garcés, “Learning from the Movement for a New Society: An Interview with George Lakey,” ''AK Press'', February 2, 2010, https://revolutionbythebook.akpress.org/2010/02/learning-from-the-movement-for-a-new-society-an-interview-with-george-lakey/.</ref> |

| | |

| | Surely many people in many places at many times throughout history have been concerned about how to make decisions in a way that feels equal and fair for all involved. It goes without saying that there are likely many genealogies of consensus; methods for collective decision-making must have many histories.<ref>To share a couple other genealogies that I am familiar with: the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, once called the Iroquois Confederacy by the French, and the League of Five Nations by the English, is made up of the Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas, and was founded as a way to unite the nations and create a peaceful means of decision making. The governance of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy runs on a spokes-council model. Another rich history of consensus comes from the organizing and governing principles of the Zapatistas in Mexico.</ref> One particular history of consensus that I was first exposed to in my late teenage years can be traced through a Christian religious community called Quakers. Founded in the 1650s by George Fox, the core philosophy of Quakerism lies in a devotion to peace and nonviolence, coupled with the belief that God is present in everyone, as a sacred light within each of us, thus nullifying the need for clergy to interpret God's will. This democratic belief in equal access to the divine led to a disavowal of formal ministry and set forms of worship, as well as a rejection of many prevailing Christian hierarchies. For example, even at its founding in the 17th century, women were understood to have equal access to God and could therefore minister to the public and have leadership roles in the community. |

| | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| | [[File:2a-communities-no-27Page01.jpg|thumb|Cover of 'Communities: Journal of Cooperative Living,' July/August 1977. https://wiki2print.hackersanddesigners.nl/wiki/mediawiki/images/e/ec/2a-communities-no-27.pdf]] |

| | </div> |

| | As it relates to our focus here, this also deeply influenced how communities of Quakers organized themselves. In the tradition of Quaker worship, community members sit together silently until one feels moved to share an insight or message with the congregation. Quakers still use this philosophy for organizational functions too, for business meetings, and social or political initiatives. Similar to a meeting for worship, participants take turns expressing ideas, not necessarily responding directly to one another. Discussion continues until there is a sense that all participants feel agreement about what is to be done, or once all participants can at least accept the direction the decision has taken. Though this is often time consuming, Quakers are invested in consensus because within the origin of its practice is the notion that each of us contains the presence of the divine. As historian A. Paul Hare writes, |

| | |

| | <blockquote>“For over 300 years, the members of the Society of Friends have been making group decisions without voting. Their method is to find a sense of the meeting, which represents a consensus of those involved. Ideally, this consensus is not simply unanimity or an opinion on which all members happen to agree, but an actual unity, a higher truth which grows from the consideration of divergent opinions and unites them all.”<ref> A. Paul Hare, “Group Decision by Consensus: Reaching Unity in the Society of Friends,” ''Sociological Inquiry'' 43, no. 1 (Jan 1973): 75, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1973.tb01153.x. </ref></blockquote> |

| | |

| | Because of this long-standing practice, those raised within the Quaker faith were intimately familiar with this method of decision-making and increasingly brought these methods into other spheres of their lived realities. Without knowing this history, it may come as a shock that the use of consensus decision-making in most radical and leftist organizations in the U.S. and Europe today—from Occupy Wall Street to Extinction Rebellion—has roots in the beliefs and practices of the Quakers. |

| | |

| | As mentioned above, a core tenet of Quakerism is peace, not solely passive in the sense of not engaging in violence and war, but also through actively working to engender non-violence, in a similar vein, perhaps, as other religious groups give alms or engage in community service projects. The post-war period in America was mired in violence and struggle both at home and abroad. The after-effects of the atomic bomb and the rise of nuclear power, the Vietnam War and other US imperialist incursions into East Asia, and the struggle for civil rights, Black power, and the women’s liberation movement saw a concomitant rise in televised and broadcasted violence (and its normalization) within public life in 1960s America. It was in this context that in 1966 a group of activist Quakers founded A Radical Quaker Action Group. Focused primarily on creative, direct, nonviolent campaigns, as a way of making public examples and methodologies for making peace and protesting violence, one of A Radical Quaker Action Group’s key methods was using sailing boats and the distinct legal territory and status of the ocean as a means for sharing aid. In one such action, they sent antimalarial and antibacterial drugs and bandages to Hiroshima, and in a later action they sailed with similar supplies to Vietnam. The idea behind this was to identify means of doing direct nonviolence, not symbolic actions or protests in hopes of changing state policy. For A Radical Quaker Action Group, war was viewed as an inherent aspect of the system of capitalism, and social inequality was understood as a form of violence maintained by the threat of state violence. To work for peace and equality, to abide by the Quaker testimony of peace, one must engage in social change. This was not to say, however, that they did not have creative ideas about how to enact social change. One of their key tenets was the notion of “image defeat.” In addition to the hoped-for impact of direct action, they aimed to create attention-grabbing, imaginative stories and images that would garner outsized media attention, overshadowing or even replacing news coverage sympathetic to the state and state violence. For example, when their boat the Phoenix sailed to Vietnam, it appeared on the front cover of many newspapers, supplanting the image of the U.S. making war with an image of a small group of radical Quakers sailing to Vietnam with food and supplies. |

| | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| | [[File:1-Phoenix-1967.jpg|thumb|Phoenix in Hong Kong harbor, en route to North Vietnam, 1967.]] |

| | </div> |

| | A Radical Quaker Action Group eventually disbanded, but their impact reverberated both within Quaker activist circles and more broadly amongst organizations tied to the New Left. Some people involved with these earlier activities were then involved in the formation of another group, Movement for a New Society (MNS). Self-identified as a feminist, radical, non-violent organization, Movement for a New Society was active from 1971 to 1988. With chapters in about a dozen cities across the U.S. and a hub in Philadelphia, the ideas they developed connected with many other activist struggles at the time, such as feminist liberation, environmental organizing, and anti-nuke activism. At its core, the group’s ethos was about sharing knowledge with one another and connecting the internal workings of community organizing with the external goals of these campaigns, through trainings and typical activist organizing, but also by practicing unlearning and doing self-work. This manifested as an ongoing commitment to doing anti-oppression training among them and a study format they termed “macro-analysis” seminars. The purpose of these seminars was to ensure they committed to and made time for study and inquiry, not just goal-oriented aims. Through this community study structure, they could practice recognizing and undoing their own internalized racism, sexism, homophobia, and classism. The macro-analysis seminars and study groups were modeled on extant popular education efforts of the time, especially from the civil rights movement, feminist consciousness-raising, and the ideas of critical pedagogue Paulo Freire. |

| | |

| | In its first pamphlet, MNS positioned its distinct understanding of community-organizing, and declared its opposition to, |

| | |

| | <blockquote>“Traditional forms of organization, from [the multinational corporation] ITT to the PTA [Parent-Teacher Association]…for they exhibit the sexism and authoritarianism we seek to supplant. Our goals must be incorporated into the way we organize. Thus the movement we build must be egalitarian and non-centralized.”<ref>Andrew Cornell, ''Oppose and Propose: Lessons from Movement for a New Society'' (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2011), 24.</ref></blockquote> |

| | |

| | At its core, MNS was concerned with creating different social relations, and saw its own community as a place to practice these ideas in the here and now, while working for these changes within society as a whole. This led MNS to integrate the seemingly external efforts of political organizing with the internal growth of becoming more socially aware and empathetically attuned, as a way of living closer to and more in accord with the world they wanted to see. Practically speaking, MNS built infrastructure to facilitate livelihoods, such as housing co-ops, food co-ops, a publisher, reading rooms, and “counter-institutions” as they termed them, but this philosophy also deeply influenced how they did process, leading to the development of infrastructures for organizing people, dialogue, and decision-making. From this came structures such as affinity groups, macro-analysis seminars and spokes-councils.<ref>I understand the spokes-council governance structure as having Indigenous origins, but I don’t know the details of how MSN developed its approach to spokes-councils or where it came from.</ref> These developments and the way of thinking that fueled them exemplify the concept of “prefigurative politics,” as coined by sociologist Wini Breines, who identified a central tenet of the work of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) as the effort to “create and sustain within the lived practice of the movement, relationships and political forms that ‘prefigured’ and embodied the desired society.”<ref>Wini Breines, ''Community and Organization in the New Left'', 1962-1968: The Great Refusal, 2nd ed. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1989), 6.</ref> |

| | |

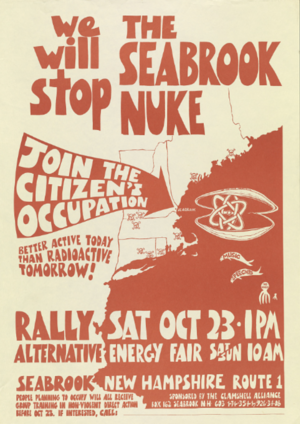

| | MNS had the opportunity to promulgate many of these practices more widely because of their involvement in organizing with the Clamshell Alliance to protest the proposed Seabrook Nuclear power plant in 1977. Due to the collective organizing efforts, 1400 people were peaceably arrested, collectively refused bail, and were then able to use the time held for two weeks in large armory buildings to collectively study, organize, and train themselves, testing many of the methods MNS had elaborated. Since then (and via other routes), techniques of horizontal organizing and consensus decision-making have spread and morphed across various social movements, and more broadly through universities, socially-engaged artistic practices, and many other activist adjacent fields. |

| | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| | [[File:3- Clamshelloct77.png|thumb|We will stop the Seabrook Nuke: join the citizen's occupation, Clamshell Alliance, 1977.]]</div> |

| | |

| | While it might feel commonplace to say, “let’s work in a horizontal way,” “let’s decide this through consensus,” or “let’s create affinity groups for organizing a multi-part project,” it feels important to trace these genealogies and the histories and contexts that brought us here. In one context, consensus is fetishized as a goal in and of itself, while in another, it is demonized due to the tepid, watered-down decisions it leads to in lieu of complete political deadlock. In analyzing the development of direct democratic structures such as Occupy and other recent social movements, commentators David Graeber and Cindy Milstein have both suggested that “[c]onsensus is both our ends and our means of struggle.”<ref> Andrew Cornell, “[c]onsensus: what it is, what it isn’t, where it comes from and where it must go”, in ''We Are Many: Reflections on Movement Strategy From Occupation to Liberation'', ed. by Kate Khatib, Margaret Killjoy, and Mike McGuire (Oakland: AK Press, 2012), 164.</ref> I am sympathetic to this notion, and I too want to be part of a society that is participatory, egalitarian, and self-organizing. But I think we need to understand consensus as multifaceted and complex, with both histories and contexts tied to these methodologies, worthy of attention and study, not a catch-all phrase and simple concept that can magically make direct democracy possible in and of itself. |

| | |

| | ==== Part II: Some ideas for doing consensus together ==== |

| | '''What is consensus?'''<br> |

| | Consensus is a collective creative problem-solving process, created through: |

| | * receptive, perceptive, and empathic listening |

| | * digestion and connecting—finding commonalities and threads between ideas and concerns (and noting differences and dissonance) |

| | * synthesizing and translating—voicing propositions that bring together divergent ideas, concerns, and approaches |

| | |

| | '''What is consensus good for?'''<br> |

| | Movement for a New Society members saw at least three key benefits to the consensus process: |

| | * it helps to empower more reserved and less experienced participants, creating a more even field for all |

| | * it keeps in check the sometimes-competing egos in an organization or group |

| | * the deeply considered discussion aspect of consensus is useful in a group’s early state when it is “searching” for new ideas and building unity in the group |

| | |

| | '''Some conditions needed for consensus: '''<br> |

| | |

| | * '''Shared desires''' |

| | The group needs to share a clear common desire or goal(s), and be willing to work together toward this. It needs to be clear what needs to be decided upon collectively and what can be left to individuals. Discuss together what our goals are and how we will get there. When conflict and differences inevitably arise, return to the common goal(s) to refocus the conversation. |

| | |

| | * '''Nurturing trust, accountability and openness''' |

| | We need to be able to trust that each of us arrives with the intention of working together. We also need to nurture spaces where all voices are heard and valued. Sometimes there is much to do, long before decisions get made, just to get to a point wherein a community or group of people is ready and able to speak together in that way. This isn’t an effort that can be skipped. George Lakey uses the metaphor of a container, |

| | |

| | <blockquote>“I call the kind of social order that supports safety, a ‘container.’ The metaphor of container suggests that it might be thin or thick, weak or robust. A strong container has walls thick enough to hold a group doing even turbulent work, with individuals willing to be vulnerable in order to learn.”<ref>George Lakey, ''Facilitating Group Learning: Strategies for Success with Adult Learners'' (Hoboken: Jossey-Bass, 2010), 11.</ref></blockquote> |

| | |

| | Part of accountability is also accountability to ourselves, to listen internally and openly express our desires (what we’d like to see happen), and our needs (what we must have happen in order to be able to support a decision). If everyone is able to talk openly then the group will have the information it requires to take everyone’s positions into account and come up with a solution that everyone can support. Consensus will inevitably fail if needs aren’t shared publicly or if they are ignored when voiced. |

| | |

| | * '''Commitment to practicing consensus together''' |

| | Everyone needs to be willing to be present in all senses of the word. This means being deeply honest about what it is you want or don’t want, and listening empathetically to what others have to say. Everyone must be willing to shift their positions and opinions, and to notice assumptions they may have been leaning on. Further, we need to be open to alternative and unexpected solutions, and accept the “good enough.” |

| | |

| | * '''Enough time and capacity''' |

| | Consensus takes effort, so it’s not wise to use it for decisions that don’t warrant such energy. Learning to work together with others in this way builds over time, but each scenario or decision deserves consideration and attention. Rushing a process is like shooting it in the foot; inevitably needs or crucial information will be missed or ignored and thus decisions taken will require reworking and revision later. Cultivate circumstances that make it feasible for your group to have time and capacity for this work. Be realistic about what’s possible with the time you all can collectively give, determine limits ahead of time, and make sure this is clearly shared with everyone. Think of concerns and needs that will pull people away from this process and collectively arrange for these needs ahead of time, such as food, rest breaks, suitable space, childcare, etc. |

| | |

| | * '''Honoring process''' |

| | It’s a necessity to have a clear (and accountable) process for making decisions and to do everything possible to ensure that all those present have a shared understanding of how the process works. If specific methods, hand signals, etc. will be used, this needs to be outlined and made clear for everyone. A clear statement or outline of what is aimed for (see “Shared desires”), and information and planning for the meeting (see “Enough time and capacity”) should be voiced from the outset. Honoring the process means listening to where it takes you collectively even when it leads you to an unexpected conclusion. It also means collectively agreeing to take care of the conversation, noticing when things stray off-topic and holding collective responsibility toward guiding the process, while being mindful of the limits and capacity of all involved. |

| | |

| | * '''Being present''' |

| | In consensus we all need to actively participate. We need to listen intently to what everyone has to say, while also voicing our thoughts and feelings about the matter. The process should hold space for all involved. This is possible by being present as a listener but also by being open and vulnerable to share and to speak. Being present asks that each of us proactively imagines and seeks solutions that look out for everyone involved. |

| | |

| | https://drop.hackersanddesigners.nl/17-04-2021-intro-presentation.mp4 |

| | |

| | <small>'''Angela Jerardi''' is a writer and curator, arboreal feminist (killjoy) and art school permaculturalist.</small> |

| </div> | | </div> |

A basic diagram for doing consensus

A basic diagram for doing consensus

On consensus, in two parts

Angela Jerardi

The following material was originally collected and delivered as a talk, in an effort to do two things: 1) To tell the story of one of the origins of consensus and its role in decision-making through a situated approach, and 2) To share some practical nuts and bolts learnings on how consensus can be put into practice.

Part I: A short and partial history of one genealogy of consensus[1]

“We are so accustomed to majority rule as a necessary part of democracy that it is difficult to imagine any democratic system working without it. It is true that it is better to count heads than to break them… but the party system has proved very far from providing the ideal democracies of people’s dreams.”[2]

This quote takes us slightly astray from where I want to go, but it gets us thinking along a helpful track. For one, why is it so challenging to imagine democracy without majority rule? For many of us, the image of democracy is limited to its representational forms—someone else acting on our behalf, our direct role relegated to that of a voter, and the often entrenched non-action, bickering, and corruption endemic within systems built on political parties and coalition governments. The aim of this text is to think democracy otherwise, proposing consensus as a means for doing democracy. Consensus is understood primarily as a method for decision-making, but I want to argue that it also offers a way of organizing methods of thinking and processing in groups that can create infrastructure to develop non-hierarchical collaborations, build community, identify conflict, and gestate shared values and intentions. As community-organizer and facilitator George Lakey puts it, “Consensus is a structural attempt to get equality to happen in decision making.”[3]

Surely many people in many places at many times throughout history have been concerned about how to make decisions in a way that feels equal and fair for all involved. It goes without saying that there are likely many genealogies of consensus; methods for collective decision-making must have many histories.[4] One particular history of consensus that I was first exposed to in my late teenage years can be traced through a Christian religious community called Quakers. Founded in the 1650s by George Fox, the core philosophy of Quakerism lies in a devotion to peace and nonviolence, coupled with the belief that God is present in everyone, as a sacred light within each of us, thus nullifying the need for clergy to interpret God's will. This democratic belief in equal access to the divine led to a disavowal of formal ministry and set forms of worship, as well as a rejection of many prevailing Christian hierarchies. For example, even at its founding in the 17th century, women were understood to have equal access to God and could therefore minister to the public and have leadership roles in the community.

As it relates to our focus here, this also deeply influenced how communities of Quakers organized themselves. In the tradition of Quaker worship, community members sit together silently until one feels moved to share an insight or message with the congregation. Quakers still use this philosophy for organizational functions too, for business meetings, and social or political initiatives. Similar to a meeting for worship, participants take turns expressing ideas, not necessarily responding directly to one another. Discussion continues until there is a sense that all participants feel agreement about what is to be done, or once all participants can at least accept the direction the decision has taken. Though this is often time consuming, Quakers are invested in consensus because within the origin of its practice is the notion that each of us contains the presence of the divine. As historian A. Paul Hare writes,

“For over 300 years, the members of the Society of Friends have been making group decisions without voting. Their method is to find a sense of the meeting, which represents a consensus of those involved. Ideally, this consensus is not simply unanimity or an opinion on which all members happen to agree, but an actual unity, a higher truth which grows from the consideration of divergent opinions and unites them all.”[5]

Because of this long-standing practice, those raised within the Quaker faith were intimately familiar with this method of decision-making and increasingly brought these methods into other spheres of their lived realities. Without knowing this history, it may come as a shock that the use of consensus decision-making in most radical and leftist organizations in the U.S. and Europe today—from Occupy Wall Street to Extinction Rebellion—has roots in the beliefs and practices of the Quakers.

As mentioned above, a core tenet of Quakerism is peace, not solely passive in the sense of not engaging in violence and war, but also through actively working to engender non-violence, in a similar vein, perhaps, as other religious groups give alms or engage in community service projects. The post-war period in America was mired in violence and struggle both at home and abroad. The after-effects of the atomic bomb and the rise of nuclear power, the Vietnam War and other US imperialist incursions into East Asia, and the struggle for civil rights, Black power, and the women’s liberation movement saw a concomitant rise in televised and broadcasted violence (and its normalization) within public life in 1960s America. It was in this context that in 1966 a group of activist Quakers founded A Radical Quaker Action Group. Focused primarily on creative, direct, nonviolent campaigns, as a way of making public examples and methodologies for making peace and protesting violence, one of A Radical Quaker Action Group’s key methods was using sailing boats and the distinct legal territory and status of the ocean as a means for sharing aid. In one such action, they sent antimalarial and antibacterial drugs and bandages to Hiroshima, and in a later action they sailed with similar supplies to Vietnam. The idea behind this was to identify means of doing direct nonviolence, not symbolic actions or protests in hopes of changing state policy. For A Radical Quaker Action Group, war was viewed as an inherent aspect of the system of capitalism, and social inequality was understood as a form of violence maintained by the threat of state violence. To work for peace and equality, to abide by the Quaker testimony of peace, one must engage in social change. This was not to say, however, that they did not have creative ideas about how to enact social change. One of their key tenets was the notion of “image defeat.” In addition to the hoped-for impact of direct action, they aimed to create attention-grabbing, imaginative stories and images that would garner outsized media attention, overshadowing or even replacing news coverage sympathetic to the state and state violence. For example, when their boat the Phoenix sailed to Vietnam, it appeared on the front cover of many newspapers, supplanting the image of the U.S. making war with an image of a small group of radical Quakers sailing to Vietnam with food and supplies.

A Radical Quaker Action Group eventually disbanded, but their impact reverberated both within Quaker activist circles and more broadly amongst organizations tied to the New Left. Some people involved with these earlier activities were then involved in the formation of another group, Movement for a New Society (MNS). Self-identified as a feminist, radical, non-violent organization, Movement for a New Society was active from 1971 to 1988. With chapters in about a dozen cities across the U.S. and a hub in Philadelphia, the ideas they developed connected with many other activist struggles at the time, such as feminist liberation, environmental organizing, and anti-nuke activism. At its core, the group’s ethos was about sharing knowledge with one another and connecting the internal workings of community organizing with the external goals of these campaigns, through trainings and typical activist organizing, but also by practicing unlearning and doing self-work. This manifested as an ongoing commitment to doing anti-oppression training among them and a study format they termed “macro-analysis” seminars. The purpose of these seminars was to ensure they committed to and made time for study and inquiry, not just goal-oriented aims. Through this community study structure, they could practice recognizing and undoing their own internalized racism, sexism, homophobia, and classism. The macro-analysis seminars and study groups were modeled on extant popular education efforts of the time, especially from the civil rights movement, feminist consciousness-raising, and the ideas of critical pedagogue Paulo Freire.

In its first pamphlet, MNS positioned its distinct understanding of community-organizing, and declared its opposition to,

“Traditional forms of organization, from [the multinational corporation] ITT to the PTA [Parent-Teacher Association]…for they exhibit the sexism and authoritarianism we seek to supplant. Our goals must be incorporated into the way we organize. Thus the movement we build must be egalitarian and non-centralized.”[6]

At its core, MNS was concerned with creating different social relations, and saw its own community as a place to practice these ideas in the here and now, while working for these changes within society as a whole. This led MNS to integrate the seemingly external efforts of political organizing with the internal growth of becoming more socially aware and empathetically attuned, as a way of living closer to and more in accord with the world they wanted to see. Practically speaking, MNS built infrastructure to facilitate livelihoods, such as housing co-ops, food co-ops, a publisher, reading rooms, and “counter-institutions” as they termed them, but this philosophy also deeply influenced how they did process, leading to the development of infrastructures for organizing people, dialogue, and decision-making. From this came structures such as affinity groups, macro-analysis seminars and spokes-councils.[7] These developments and the way of thinking that fueled them exemplify the concept of “prefigurative politics,” as coined by sociologist Wini Breines, who identified a central tenet of the work of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) as the effort to “create and sustain within the lived practice of the movement, relationships and political forms that ‘prefigured’ and embodied the desired society.”[8]

MNS had the opportunity to promulgate many of these practices more widely because of their involvement in organizing with the Clamshell Alliance to protest the proposed Seabrook Nuclear power plant in 1977. Due to the collective organizing efforts, 1400 people were peaceably arrested, collectively refused bail, and were then able to use the time held for two weeks in large armory buildings to collectively study, organize, and train themselves, testing many of the methods MNS had elaborated. Since then (and via other routes), techniques of horizontal organizing and consensus decision-making have spread and morphed across various social movements, and more broadly through universities, socially-engaged artistic practices, and many other activist adjacent fields.

While it might feel commonplace to say, “let’s work in a horizontal way,” “let’s decide this through consensus,” or “let’s create affinity groups for organizing a multi-part project,” it feels important to trace these genealogies and the histories and contexts that brought us here. In one context, consensus is fetishized as a goal in and of itself, while in another, it is demonized due to the tepid, watered-down decisions it leads to in lieu of complete political deadlock. In analyzing the development of direct democratic structures such as Occupy and other recent social movements, commentators David Graeber and Cindy Milstein have both suggested that “[c]onsensus is both our ends and our means of struggle.”[9] I am sympathetic to this notion, and I too want to be part of a society that is participatory, egalitarian, and self-organizing. But I think we need to understand consensus as multifaceted and complex, with both histories and contexts tied to these methodologies, worthy of attention and study, not a catch-all phrase and simple concept that can magically make direct democracy possible in and of itself.

Part II: Some ideas for doing consensus together

What is consensus?

Consensus is a collective creative problem-solving process, created through:

- receptive, perceptive, and empathic listening

- digestion and connecting—finding commonalities and threads between ideas and concerns (and noting differences and dissonance)

- synthesizing and translating—voicing propositions that bring together divergent ideas, concerns, and approaches

What is consensus good for?

Movement for a New Society members saw at least three key benefits to the consensus process:

- it helps to empower more reserved and less experienced participants, creating a more even field for all

- it keeps in check the sometimes-competing egos in an organization or group

- the deeply considered discussion aspect of consensus is useful in a group’s early state when it is “searching” for new ideas and building unity in the group

Some conditions needed for consensus:

The group needs to share a clear common desire or goal(s), and be willing to work together toward this. It needs to be clear what needs to be decided upon collectively and what can be left to individuals. Discuss together what our goals are and how we will get there. When conflict and differences inevitably arise, return to the common goal(s) to refocus the conversation.

- Nurturing trust, accountability and openness

We need to be able to trust that each of us arrives with the intention of working together. We also need to nurture spaces where all voices are heard and valued. Sometimes there is much to do, long before decisions get made, just to get to a point wherein a community or group of people is ready and able to speak together in that way. This isn’t an effort that can be skipped. George Lakey uses the metaphor of a container,

“I call the kind of social order that supports safety, a ‘container.’ The metaphor of container suggests that it might be thin or thick, weak or robust. A strong container has walls thick enough to hold a group doing even turbulent work, with individuals willing to be vulnerable in order to learn.”[10]

Part of accountability is also accountability to ourselves, to listen internally and openly express our desires (what we’d like to see happen), and our needs (what we must have happen in order to be able to support a decision). If everyone is able to talk openly then the group will have the information it requires to take everyone’s positions into account and come up with a solution that everyone can support. Consensus will inevitably fail if needs aren’t shared publicly or if they are ignored when voiced.

- Commitment to practicing consensus together

Everyone needs to be willing to be present in all senses of the word. This means being deeply honest about what it is you want or don’t want, and listening empathetically to what others have to say. Everyone must be willing to shift their positions and opinions, and to notice assumptions they may have been leaning on. Further, we need to be open to alternative and unexpected solutions, and accept the “good enough.”

Consensus takes effort, so it’s not wise to use it for decisions that don’t warrant such energy. Learning to work together with others in this way builds over time, but each scenario or decision deserves consideration and attention. Rushing a process is like shooting it in the foot; inevitably needs or crucial information will be missed or ignored and thus decisions taken will require reworking and revision later. Cultivate circumstances that make it feasible for your group to have time and capacity for this work. Be realistic about what’s possible with the time you all can collectively give, determine limits ahead of time, and make sure this is clearly shared with everyone. Think of concerns and needs that will pull people away from this process and collectively arrange for these needs ahead of time, such as food, rest breaks, suitable space, childcare, etc.

It’s a necessity to have a clear (and accountable) process for making decisions and to do everything possible to ensure that all those present have a shared understanding of how the process works. If specific methods, hand signals, etc. will be used, this needs to be outlined and made clear for everyone. A clear statement or outline of what is aimed for (see “Shared desires”), and information and planning for the meeting (see “Enough time and capacity”) should be voiced from the outset. Honoring the process means listening to where it takes you collectively even when it leads you to an unexpected conclusion. It also means collectively agreeing to take care of the conversation, noticing when things stray off-topic and holding collective responsibility toward guiding the process, while being mindful of the limits and capacity of all involved.

In consensus we all need to actively participate. We need to listen intently to what everyone has to say, while also voicing our thoughts and feelings about the matter. The process should hold space for all involved. This is possible by being present as a listener but also by being open and vulnerable to share and to speak. Being present asks that each of us proactively imagines and seeks solutions that look out for everyone involved.

https://drop.hackersanddesigners.nl/17-04-2021-intro-presentation.mp4