|

|

| (67 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| <div> | | <div class="article Workshop-Histories-and-Practices layout-2" id="Workshop_Histories_and_Practices"> |

|

| |

|

| ===Workshop Histories and Practices===

| | <div class="hide-from-book scriptothek"> |

| <span class="author">A Conversation Between Heike Roms and Anja Groten</span> | |

|

| |

|

| ''[to be added: references of the books of scores, mostly scans]'' | | [[File:Journal-workshops.png|thumb|Walter A. Anderson, “What Makes a Good Workshop,” ''The Journal of Educational Sociology'' Vol. 24, No. 5 (January, 1951), pp. 251-261. https://wiki2print.hackersanddesigners.nl/wiki/mediawiki/images/7/74/2263639.pdf]] |

|

| |

|

| '''Introduction by Anja Groten'''

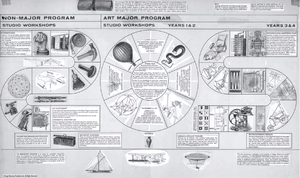

| | [[File:Studio-workshops.png|thumb|“Curriculum Plan,” Proposals for Art Education from a Year Long Study by Fluxus artist George Maciunas, 1968-1969. The image was shown in Heike Rom's presentation. http://georgemaciunas.com/exhibitions/george-maciunas-point-dappui/curriculum-plan/]] |

|

| |

|

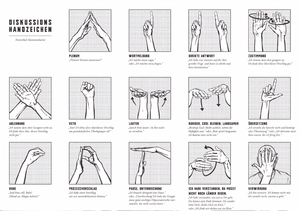

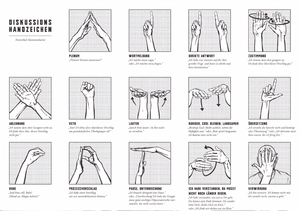

| In May 2021 I participated in an online conference about ‘The Workshop as Artistic-Political Format’, organized by Institute for Cultural Inquiry in Berlin. I was rather excited about this conference. For a while I felt the urge to reflect on the implications of the workshop as a format, and cultural phenomenon but had not found much written about the workshop as such. | | [[File:Slide-Hanna-Podig-2.png|thumb|In her talk "The Workshop as an Emancipatory Mediation Method of Resistant Practices" political activist Hanna Poddig referred to the [[#On_consensus,_in_two_parts|discussion scores]] that are also common in Consensus Decision-making practices]] |

|

| |

|

| The conference drew together practitioners from various fields of interests: choreographers, dancers, theatre makers, artists, scholars, musicians, police people, and activists, to reflect on ‘workshop' as a format, site, phenomenon, from their own specific perspectives.

| | [[File:JohnCageWaterWalk.png|thumb|"A section of Water Walk," score by John Cage]] |

|

| |

|

| The presentation "The Changing Fate of the Workshop and the Emergence of Live Art” by Heike Roms (University of Exeter) particularly resonated with me.

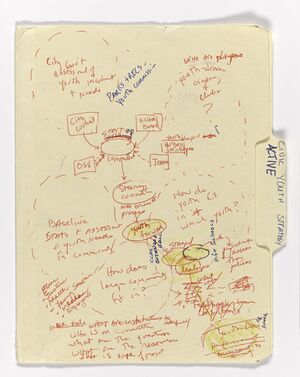

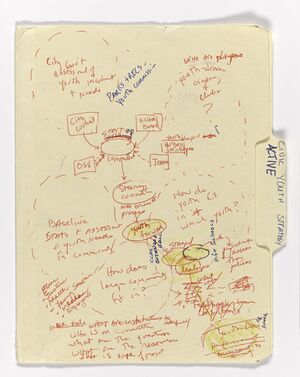

| | [[File:CivicYouth Strategy.jpg|thumb|Notes by Suzanne Lacy on the ongoing civic engagement in Oakland and the Oakland Youth Policy Initiative. Image courtesy of Suzanne Lacy.]] |

| I took excessive notes during the talk, and have been recurrently referring to some of the presented insights, propositions and exercises. Unfortunately the talk was not documented and there has not (yet) been any publication following the conference. Thus, one year later, I contacted Heike to asked if we could meet online and have a conversation about workshops that I would publish as part of the upcoming H&D publication.

| |

|

| |

| At the time of the conversation, I am in the final stages of my artistic research PhD at ACPA/PhdArts (Academy for Creative and Performing Arts at Leiden University & Royal Academy of Arts The Hague). As part of the PhD project I am exploring means of publishing (about and through) workshops – as well as (re)activating them, with the question in mind: How can workshop production become discursive, opened up and distributed in ways that is useful for others but also response-able, that is, reflective of the context?

| |

|

| |

|

| The following conversation has been edited. At moments that significant portions have been edited out, I added a note. For instance here, at the beginning of the conversation:

[Preceding to what you will read as the beginning of a conversation, Heike and I talked about, and compared the fields of artistic research in the UK and in the Netherlands, the different challenges, requirements, and criteria of pursuing an artistic research PhD.]

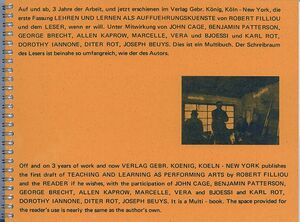

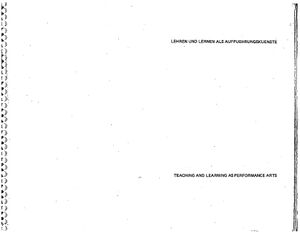

| | [[File:RobertFilliou.jpg|thumb|Page from "Teaching and Learning as Performings Arts" in 1979. Find a downloadable pdf of the publication on: https://monoskop.org/images/9/93/Robert_Filliou_Teaching_and_Learning_as_Performing_Arts.pdf]] |

|

| |

|

| | [[File:Pages from Robert_Filliou_Teaching_and_Learning_as_Performing_Arts-2.jpg|thumb|Fluxus artist Robert Filliou published the book "Teaching and Learning as Performings Arts" in 1979. The book is designed in a workbook manner, leaving space for annotation in the middle of the page https://monoskop.org/images/9/93/Robert_Filliou_Teaching_and_Learning_as_Performing_Arts.pdf]] |

| | [[File:Pages from Robert_Filliou_Teaching_and_Learning_as_Performing_Arts-3.jpg|thumb]] |

| | [[File:Pages from Robert_Filliou_Teaching_and_Learning_as_Performing_Arts-4.jpg|thumb]] |

| | [[File:Pages from Robert_Filliou_Teaching_and_Learning_as_Performing_Arts-5.jpg|thumb]] |

| | [[File:Pages from Robert_Filliou_Teaching_and_Learning_as_Performing_Arts-6.jpg|thumb]] |

| | [[File:Pages from Robert_Filliou_Teaching_and_Learning_as_Performing_Arts-7.jpg|thumb]] |

| | [[File:Pages from Robert_Filliou_Teaching_and_Learning_as_Performing_Arts-8.jpg|thumb]] |

|

| |

|

| | [[File:Pages-from-SYBILLE_TOOLKIT_WEB.jpg|thumb|Page from: Sibylle Peters, performing research: How to conduct research projects with kids and adults using Live Art strategies, (London: Live Art Development Agency, 2017), https://www.thisisliveart.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/uploads/documents/SYBILLE_TOOLKIT_WEB.pdf.]] |

|

| |

|

| '''

Anja Groten:''' I am in the midst of thinking about how to present/publish/exhibit the practical aspects of my PhD research, which is also considered the artistic part and in my case is quite convoluted because there's so many people involved. | | [[File:Pages-from-SYBILLE_TOOLKIT_WEB-2.jpg|thumb|Page from: Sibylle Peters, performing research: How to conduct research projects with kids and adults using Live Art strategies, (London: Live Art Development Agency, 2017), https://www.thisisliveart.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/uploads/documents/SYBILLE_TOOLKIT_WEB.pdf.</ref>]] |

| | </div> |

| | === Workshop Histories and Practices === |

| | <span class="author">In conversation with Heike Roms</span> |

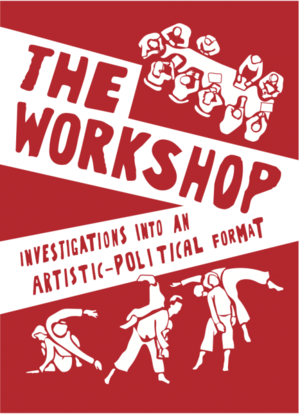

| | '''Anja Groten:''' In May 2021 I participated in an online conference titled “The Workshop as Artistic-Political Format,” organized by Institute for Cultural Inquiry in Berlin.<ref> “The Workshop: Investigations Into an Artistic-Political Format,” ICI Berlin, March 26-28, 2021, https://www.ici-berlin.org/events/the-workshop/.</ref> The conference drew together practitioners from various fields of interests, including choreographers, dancers, theater makers, artists, scholars, musicians, and activists who reflected on “workshop” as a format, site, and phenomenon from their own perspectives. Heike, you gave the presentation "The Changing Fate of the Workshop and the Emergence of Live Art,” which particularly resonated with me. |

|

| |

|

| '''Heike Roms:''' Because your work is very collaborative. | | '''Heike Roms:''' I came to the topic of workshops because in my work I look at the emergence of performance art in the sixties and seventies. I became interested in particular in the emergence of performance art within art educational contexts, in a conceptualization of a pedagogy of performance. I've read your chapter on “Workshop Production,”<ref> Anja Groten, “Workshop Production,” Figuring Things Out Together. On the Relationship Between Design and Collective Practice (PhD Diss., Leiden University, 2022).</ref> which I really enjoyed. Some of the research you've done is helpful to me because I too have found that there's actually very little written about the workshop as a practice. That is, people have written about specific workshops so you can find material on workshops given by a particular artist. But there is little reflection on the workshop as a format, as a genre, as a site, as whatever we might call it. That surprised me, given that it's sort of ubiquitous in practice. There are books on performance laboratories, for example, and there is a connected history between the workshop and labs, the studio space, and rehearsals as a format. But there is very little on the workshop, certainly within performance studies or art history discourse, so I became intrigued by this ubiquitous form that remains largely unexamined. It's great that through the work of Kai van Eikels and the 2021 conference he co-organized there's a new kind of attention being paid to it, through your work as well. But there is not enough available about the history of the workshop to help us understand at what point this flip occurred from considering the workshop as an actual physical site to approaching the workshop as an event format. You write about this as well. The two meanings, of course, continued to exist in parallel, particularly in the context of art schools. But at what point did the workshop become an event, a time-based learning experience, as well as a site of making—a ''Werkstatt''? I don't know how and when that occurred. My suspicion is that it was sometime around the fifties and sixties. |

|

| |

|

| '''

Anja Groten:''' Yes and my research is about collective practice. How to explicate this collective practice, and it open up for discussion and how to situate material residues of a collective practice such as H&D, in a way that is not read as a product, a final thing, but as part of an ongoing process that also involves many people, perspectives, places, objects and timelines.

| | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| | [[File:ICI-Homepage.png|thumb|Announcement image to the conference “The Workshop: Investigations Into an Artistic-Political Format.” https://www.ici-berlin.org/events/the-workshop/]] |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| '''

Heike Roms:''' Would you be able to submit your website?

| | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| | [[File:Anna-Halprin_Dance.jpeg|thumb|Image of the Anna Halprin’s Dance Deck, an architectonic arrangement, and workshop site that transformed dance practice, 1951-1954, with Lawrence Halprin. The image was shown by Kai Ekels in the introduction presentation of “The Workshop: Investigations Into an Artistic-Political Format.”]] |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| '''Anja Groten:''' I guess I could. But even then, it would be a lot of websites I have done, and they are all done in very specific contexts and under specific conditions, which when you are taking them out of that context they seem only half-actualized. One of my chapters is about what I call self-made platforms – digital infrastructures that that cater to online collaboration. In the context of H&D we have been building many of those. There's at least five or six of them. | | '''AG:''' There is the ''The Journal of Educational Sociology'' that was published in 1951 and refers to the first organized professional education activity under the name of a workshop. It took place at Ohio State University in 1936.<ref> The Journal of Educational Sociology, Vol. 24, No. 5 (Jan1951): 249-250, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2263638.</ref> I remember you were talking about the relation between the occurrence of workshops and the emergence of a certain resistance toward the steady structures of art schools in the fifties and sixties in the UK—a resistance to legitimized knowledge practices and skills. Art students wanted to rid themselves of a certain authority of disciplines or disciplined learning and instead wanted to take things into their own hands. |

| Anyhow, at this point I am considering to open up a publishing cycle. H&D has made it a habit to make a small experimental book every year. Workshop moments often that open up the process of making the book. It could be interesting to have the PhD examination committee as well as my PhDArts peers join these short hands on workshops and implicate them in this open processes of learning and making.

| |

|

| |

|

| The interesting part about the context of artistic research has been that there are so many different perspectives coming together and commenting on each others work. There are sculptures, dancers, photographers, film makers, designers. This environment meant for me, that I needed to look beyond design vocabularies and the dsign discourse that I had familiarized myself with. This environment opened up other ways of looking at design. I think these contexts in which disciplinary boundaries erode, may be why the workshop became a subject for me. I haven't thought about the ‘workshop' as a subject before I started at PhDArts. But then I noticed its ubiquity of the workshop within all aspects of my practice, – in my work as an educator, a designer and an organiser. I couldn’t ignore it anymore. The workshop plays also a significant role in the context of Hackers & Designers. But also here I felt we took the workshop for granted, as something inherently useful. H&D workshops are a way for us to experiment freely – next to our individual practices in a sort of no pressure situation. We get to try out new things. But at the same time, as it was also discussed in the conference that you spoke at, the workshop is also intertwined in the neo-liberalization of art and education. There seems to be a double bind in workshop-based practice. I am trying to think about how do to deal with that double-bind as a collective – a self-organised, self-determined experimental space? Why are we enjoying these workshops and how can we sustain and awareness of their implications?

| | '''HR:''' In the specific history I looked at, which is that of Cardiff College of Art, I found that there is a confluence between the workshop and two emancipatory movements. First was the move toward the workshop as a learning format through the impetus of the Bauhaus, which in the 1960s developed a huge impact on art schools across the UK. Traditionally people weren’t really talking about workshops as sites of making in the context of art schools; the workshop was the place of the plumber or the blacksmith, while artists worked in ateliers or studios. I think that the idea of the workshop as a place of making was introduced to the art school through the Bauhaus philosophy, which was a vehicle for the emancipation of art education. All of a sudden art was being approached in the same way as other practices of making were being approached. No longer did we have the sculpture atelier or the drawing room. Now there were ceramics workshops, metal workshops, printmaking workshops but also painting workshops and sculpture workshops (or ‘2D’ and ‘3D’ workshops as they were often called at the time). This move introduced a different kind of art making. |

| For me the process of writing about workshops, and practicing to writing in general, drove my attention to workshops, including the awkwardnesses and frictions that sometimes occur in these time-boxed intensive spaces. Why do these moments matter? Also, why am I often disappointed after workshop? The writing has become a really important part of the research process.

| |

|

| |

|

| '''

Heike Roms''': That’s how a PhD through practice should work – thinking through the practice and finding those moments of articulation. | | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| | [[File:Studio-workshops.png|thumb|“Curriculum Plan,” Proposals for Art Education from a Year Long Study by Fluxus artist George Maciunas, 1968-1969. The image was shown in Heike Rom's presentation. http://georgemaciunas.com/exhibitions/george-maciunas-point-dappui/curriculum-plan/]] |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| I came to the topic of workshops because I'm interested in the history of performance art. I look at the emergence of performance in the sixties and seventies and became interested in the emergence of performance art within art educational contexts, through the conceptualisation of a pedagogy of performance. That's how I hit on the workshop. I've read your chapter, which I really enjoyed. There's lots of interesting avenues there that I might think about in relation to my own work as well. Some of the reading that you've done are helpful because I have found that there's very little actually written about the workshop as a practice. People write about specific workshops so you can find material on the specific workshops of a particular artist. But there is very little reflection on the workshop as a format, as a genre, as a site, as whatever we might call it. That surprised me, given that it's sort of ubiquitous. There have been books on laboratories, for example, and there is a connected history to labs, and the studio space as well, and rehearsals . But there is actually very little on the workshop that I have found, certainly within performance study or artistic discourse. I got intrigued by this really ubiquitous form that nonetheless remains unreflected. It's great that there's this new kind of attention being paid to it through, through the conference, through the work of Kai (Kai van Eikels is one of the conference organizers], and through your work. But I'm at the point where I don't know enough yet about the history of the workshop to understand at what point this flip occurred of the workshop as a site and the workshop as an event. You write about this as well. The two meanings, of course, exist in parallel to one another, particularly in the context of art schools. But at what point did the workshop become an event rather than a site of making – a Werkstatt. I don't know how that occurred and when that occurred. My suspicion is it's somewhere around the fifties and sixties.

| | This change that occurred in art schools in the UK in the sixties through a new approach to art education known as ‘Basic Design’ was very much driven by the reception of the Bauhaus approach and in particular Joseph Itten’s ''Vorkurs'' (preliminary course). Workshop production was seen as a new, more emancipatory form of art making. It came out of the experiences of the Second World War and the desire to give art students a different sort of experience—one that connected them to the contemporary world [[#Learning_to_Experiment,_Sharing_Techniques|rather than traditional skills training]] and that aimed to overcome the distinction between art, craft and design. |

| | The second shift is where performance comes in in the 1960s. Teachers and students saying: We don't want all of that material making in the workshop. We want to make something that's ephemeral and that's collective and that's participatory. We don't want to be hammering away all day in the workshop. Instead we do this other thing where we get together and we make something that’s not actually about producing any objects, and we'll call that a workshop as well. That's the event-based rather than space-based concept of the workshop. |

| | In dance, people were already talking about workshops as events in the fifties. I don't know when the shift occurred from the workshop as a site toward the more ephemeral understanding of the workshop as event, how that happened, but it's interesting because what motivated the artists in the sixties that I have been looking at—and they explicitly say so in their notes—was that this move toward the ephemeral was about searching for more equitable relationships that do away with the teacher-student division. That division had been further cemented by the remains of the Bauhaus philosophy and its celebration of mastery. I think that was one of the key shifts toward this more [[#Scripting_Workshops|ephemeral meaning of the workshop]]. It was no longer about a master passing on knowledge to their students. It became about collective making. And everybody took collective charge and responsibility for that making. The educators on whom I've done research actually say that they wanted to get away from producing objects toward collective action. But, as you say, the workshop can very easily be co-opted like so much of the sixties was. Was that the last hurrah of collectivism? Or was it actually what lay the groundwork for the entry of neoliberalism into education as we now know it? |

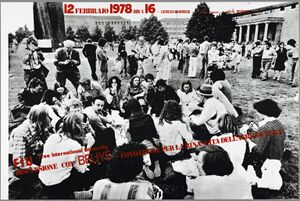

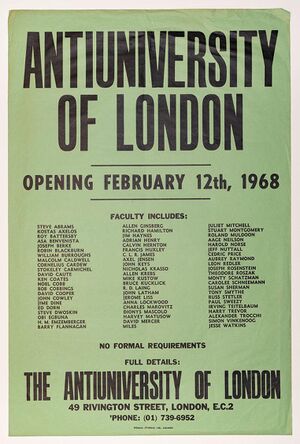

| | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| | [[File:FreeInternationalUniversity.jpeg|thumb|Announcement for the ''Free International University'']] |

| | [[File:30593911032.jpeg|thumb|Announcement for the ''Antiuniversity of London'', 1978]] |

| | </div> |

| | '''AG:''' I myself am wondering whether organizing workshops can generally be considered an emancipatory practice at all? Perhaps there cannot or should not be a general answer to this question. At the school where I work as an educator, some argue the educational system builds upon rather precarious labor conditions, where everyone works as a self-employed freelancer. Simultaneously, more and more workshops are being organized, which at times can clutter the education. Students are supposed to self-initiate and self-organize as well. They often resort to organizing workshops for each other. In my view, such conditions sometimes also show the limits of what can be accomplished with workshops. I think it's important to have more discussions about the workshop as a format and its implications for the learning economy. How to speak about and practice workshops in a way that still allows us to do the things we want to do, whilst also paying critical attention to the undesirable conditions it is intermingled with. |

| | How was it for you? Did the invitation to the conference lead you to take a deeper look at the phenomenon of the workshop? Or were you already busy with it? |

|

| |

|

| '''Anja Groten''': There was a journal published "The Journal of Educational Sociology” in 1951 which refers to a the first "organized professional education activity under the name of a workshop that was conducted at Ohio State University in 1936". There are some brilliant papers in this journal about what makes a good workshop. I only recently saw it. If I would have known about it before! [laughs]. | | '''HR:''' Yes, it would be fair to say it led to a deeper engagement with the notion of the workshop. I had been working on this material before and I've written about it too. But I had never really paid attention to the frequency of the word ‘workshop’ in the material I had researched until the invitation came to speak at the conference. It was then that I realized that the workshop is a really productive format to be talking about. |

| I remember from your talk you were implying in the field of art history that you studied, there was a bit of a resistance involved in organising workshops a resistance towards the steady structures of art schools, a resistance towards legitimized practices and skills. Art students wanted to rid themselves from a certain authority of disciplines or disciplined learning and instead take things into own hands. I'm not sure how much there was a consciousness around using the term workshop for that kind of self-organised educational initiatives? | | I wrote a paper on this before in which I talked about the idea that artists and performance educators in the sixties and seventies in the UK were creating events as a kind of [[#Critical_Coding_Cookbook|parallel institution]]. These events aimed to serve the function of an art school without replicating its hierarchical structures. This was the case in Cardiff, but also in other places in the UK such as Leeds College of Art. I was grateful that I was invited to think more about this by the conference. I looked at my examples, and it is specifically “the workshop as event” that emerged as a kind of parallel institution at the time. It wasn't really the performances these teachers and students went on to make together, but the workshop as a learning format that I think they clustered all their ideas around. |

|

| |

|

|

'''Heike Roms''': In the history that I looked at there is a confluence between the workshop and two emancipatory movements. First is the move towards the workshop that happened through the Bauhaus. That had a huge implications on the art schools in the UK. Before the sixties people were talking not really about workshops as places of making. The workshop was the place of the plumber or the blacksmith. Artists worked in ateliers or studios. The idea of the workshop as a place of making was introduced through the Bauhaus philosophy. The workshop was a vehicle for emancipatory art education. It was underlined by art making being approached as other kinds of making are approached as well. There is no longer the sculpture atelier or the or the drawing room. We now have the ceramics workshop, plastic workshop, materials workshops. That shift was already a move towards understanding and using the workshop as a site of making. This move introduced a different kind of art making and that was very strong in a place like Cardiff, which is what I've been looking at. This change that happened in the UK in the sixties was very much driven by the reception of Bauhaus and Joseph Itten's preliminary course. It was seen as a new, more emancipatory form of art making that also came out of the experiences of Second World War and wanting to give students a different sort of experience – being more connected to the contemporary world and overcoming the differences between art and design. The second shift is then when performance comes in: We don't want all of that material making in the workshop. We want to make something that's ephemeral and that's collective and that's participatory. We don't want to be hammering all day in the workshop. So we do this other thing where we get together and we make something that is not actually producing any objects, and we'll call that a workshop as well. That's the event based rather than space based workshop.

| | '''AG:''' I stumbled upon the conference last minute and wasn't aware of this whole community of performance artists and live arts who consider the workshop as an artistic medium. It's also interesting that the workshop, because of its ambiguity, manages to converge all these different worlds and unveil commonalities between them. For instance a policeman<ref>Sebastian Voigt (Polizei Berlin), "The Training of the Berlin Police Force in the Workshop"</ref> speaking about their conflict resolution workshops, and the activist who learns about tying themselves to a tree and how to negotiate with the police while doing so <ref>Hanna Poddig, "The Workshop as an Emancipatory Mediation Method of Resistant Practices"</ref>. Both speaking about the same sort of thing at the same conference from an entirely different vantage point. |

| In dance, people were talking about workshops as events in the fifties. I don't know what that shift of the workshop site towards the more ephemeral thing was and how that happened, but it's interesting because what motivated the artists that I was looking at in the sixties – and they explicitly say so in their notes – that this move towards the ephemeral was about searching for more equitable kinds of relationships that do away with that teacher student division, all the remains of the Bauhaus philosophy. I think that was one of the shifts of this ephemeral meaning of the workshop. It was going to be a space where there was no longer a master that passes on knowledge to students. It was a collective making. And everybody took collective charge and responsibilities in that making. And the people that I've done research on, they actually say that they wanted to get away from producing objects as well. But, as you say, the workshop can then be very quickly co-opted like so much of the sixties. Was that the last sort of last kind of hurrah of collectivism? Or was that actually what lay the groundwork for neoliberalism, as we know it?

| |

|

| |

|

| '''

Anja Groten''': That's a painful thought, especially for someone who enjoys organising workshops. But I'm wondering myself can organising workshops be considered an emancipatory practice at all? Perhaps there cannot, or should not be a general answer to this question. It's about context and where you organise these sort of ephemeral learning situations. In the school where I work as an educator, some argue the educational system builds upon rather precarious labour conditions, where everyone works as a freelancer. There seem to be also more and more workshops organized, that may clutter the education to some degree. Students are supposed to self-initiate and self-organize. In my view, such a condition can also show the limits to what can be accomplished with workshops. I think it's therefore important to have more discussions about the workshop as a format and it's implications in the learning economy. How to speak about and practice workshops in a way that still allows us to do the things we want to do, but on the other hand, also pays critical attention to the conditions it is intermingled with.

| | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| | [[File:Slide-Hanna-Podig-2.png|thumb|In her talk "The Workshop as an Emancipatory Mediation Method of Resistant Practices" political activist Hanna Poddig referred to the [[#On_consensus,_in_two_parts|discussion scores]] that are also common in Consensus Decision-making practices]] |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| How was it for you? Did the invitation to the conference lead you to look more into the workshop phenomenon? Or where you already busy with it?

| | You emphasized that a lot of the artists you researched were also educators. It was great to hear that engaged with in such an explicit manner. I don’t often hear about how the practices of artists and designers continue to evolve within particular educational environments, after they have completed their studies too. I find that many great artists and designers are also teachers and I personally don’t draw a harsh distinction between being an educator and being a designer. The practices go hand in hand. But I found that there are not many records of the teaching practices of artists and designers. Another thing from your talk that really stayed with me was your re-enactment of a workshop. You showed some pictures and I found them so interesting and also funny. In your re-enactment, you imagined through physical exercises what the workshop might have looked like. You referred to one specific artist educator, whose name I don’t recall. |

|

| |

|

| '''Heike Roms''': That would be fair to say that, yes. I had been working on this material before and I've written about it before, but actually sort of never really considered the frequency of the word workshop popping. But I never paid attention to it until the invitation came and then I realized, actually, it's a really productive thing to be talking about. | | '''HR:''' His name is John Gingell, and he is not particularly well known. I never met him in person, as he had already passed away by the time I became interested in his work. He had a sculptural practice, and a few of his public artworks are still on view in Cardiff, and some of this work has been exhibited in London. But really he was an educator. That was his main practice. He formed and shaped generations of art students. He was not the type of person to write manifestos, or write a lot in general, but I've been very fortunate because his family has allowed me to look at all of his materials, which are now kept in the attic of one of his daughters. He didn't leave a written philosophy of teaching or anything like that, just really random notes or little statements that he put together for the art school in order to justify what he was doing, or presentation outlines and things like that. |

| | I didn't re-enact any of his workshops because they were very sketchily documented. He was not somebody who kept a particularly developed [[#Channeling_Listeners|documentation]] or scoring practice. If I think about my own [[#Across_Distance_and_Difference|teaching]], I don't either. When I enter a classroom, I often just jot down some notes on the exercises I want to do. They're just little prompts, which aren’t accompanied with much explanation. In years to come, if somebody were to look at my teaching notes, they too wouldn’t be able to make much sense of what I was doing in the classroom. I don't think that's unusual. Anyway, I have contact with one of Gingell’s students from the late 1960s, the artist John Danvers, who also taught at the art school for a number of years in the seventies. He was very influenced by John Cage, so his own artistic practice was already very score-based. When he became a teacher his teaching practice was very well documented. He documented the exercises alongside photos of the students doing the exercises. He has quite substantive documentation on the courses he taught at Cardiff. |

|

| |

|

| I had done a paper on this before where I talked about the idea that artists and performance educators in the sixties and seventies in the UK were creating events as a kind of parallel institution. These events would sort of serve the kind of the function of an art school without replicating its structures. That was the case in Cardiff, but also in other places. I had written about that before, but never really focused on the workshop as a format before. I was grateful that the conference invited me to to think more about it. I looked at my examples and it is really specifically the workshop as events that became kind of the parallel institution. It wasn't really the performances they made, it was the workshop itself as a learning format that I think they really clustered all their ideas around.

| | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| 00:21:45

Anja Groten: I stumbled upon the conference last minute and wasn't aware of this whole community of performance artists and of the live arts who consider the workshop an artistic medium. It's also interesting that the workshop, because of its ambiguity manages to brings together these different worlds and unveils commonality. A policeman speaking about their conflict resolution workshops, and the activist who learns in a workshop about tying themselves to a tree and how to negotiate the police while doing so. Both speaking about the same thing from an entirely different vantage point.

| | [[File:JohnCageWaterWalk.png|thumb|"A section of Water Walk," score by John Cage]] |

| I also remember you were emphasising the the fact that a lot of the artists you researched were also educators. I thought it was great to hear that really explicitly. I don’t often hear about how artists and designers practices continue to evolve within particular educational environments also after they completed their studies. Many artists and designers are also teachers and sometimes I personally don’t draw a harsh distinction between being an educator and being a designer. It goes hand in hand. But there is not often much record of the teaching practices of artists and designers. What also really stayed with me from your talk was the re-enactment of a workshop you did. I think you showed some pictures and I found them so interesting and also funny. They showed how you reenacted a workshop, imagining through physical exercises what the workshop might have looked like. You were referring to one specific artist educator, but I couldn't really find their name anywhere.

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| '''

Heike Roms''': He is not well known at all, which is also interesting. His name was John Gingle. I never met him in person. He had already passed away by the time I became interested in his work. He had an artistic practice. There's are a few public artworks of his scattered around. He did a little bit of work exhibited in London – but he was really an educator. That's what he was. He formed and shaped generations of art students. He's also not one of those people who left manifestos or has written a lot. It's really just kind of notes that I have looked through and I've been very lucky in that his family has allowed me to look at all of his materials, which are all in the attic of one of his daughters. It's just mainly been a process of looking through lots and lots of random notes. He didn't leave a philosophy of teaching or anything like that. It's just really random notes or little things that he might have put together for the art school in order to justify what he was doing or a little note on yeah, kind of a presentation or presentation notes and things like that.

| | Interestingly, one of his regular classes in the early 1970s for Cardiff College of Art was a workshop about the use of sounds and words, which was unusual for an art school context. I invited him in 2013 to re-enact the workshop as part of the Experimentica Festival in Cardiff. Anybody could attend, but it was mainly my friends who came [laughs]. A lot of the people who attended were theatre people, and their feedback was that Danvers’ exercises and the approach that he took spoke very much of a visual arts kind of sensibility. Even though he was working with words and sounds—which have a theatrical dimension—their purpose was much less about what theatre workshops tend to focus on, such as the interpretation of words or meaning-making. Instead, Danvers’ workshop was much more about the visual qualities of words and sounds. There was much more concern about spatiality and the sculptural qualities of words. Danvers approached his teaching practice very much as a conceptual practice, and so it was fairly easy to reconstruct what he did in his workshops. I've always been intrigued by this hidden history of pedagogy within the emergence of experimental art. We read a lot about John Cage and his teaching at the New School in New York, but I often think, what did they actually do in his classes? There are some accounts of his students about the improvisations they did with Cage, but very little. I'm intrigued to learn more. Beuys too was a teacher as well as an artist, who considered teaching his ‘greatest work of art’ and a key part of his practice. There are others, too, like Suzanne Lacy and Allan Kaprow, who both taught at CalArts. In fact, a lot of the canonical performance artists were also often teachers. Some of them, Kaprow, for instance, also wrote about education. |

|

| |

|

| I didn't re-enact any of his workshops because a lot of his workshops are just very, very sketchily documented. He was not somebody who kept a very developed kind of scoring practice and if I think about my own teaching. I don't either actually. I mean a lot of times when I go to a classroom, I have just have some notes on the exercises I want to do and I know them. So they're just little aid memoirs to me. I don't really explain them in my notes. If somebody in years to come will look at my teaching notes, they might also not really make sense of what it is that I was doing in the classroom. I don't think that's unusual. But I have quite a bit of contact with one of his students who also taught at the art school for a number of years and who is still around actually and now lives in Exeter . He was very influenced by John Cage so his own artistic practice was very score based already. When he became a teacher, all of his teaching practice was very well documented. He does has exercises alongside photos of the students that did the exercises. He has got quite substantive documentation of the courses that he taught. Interestingly, one of the classes he taught was a word course – about sounds and words, which was unusual for an art school context. I invited him. So we did the re-enactment together. So it wasn't just me taking the notes, but actually he was sort of revisiting his own practice. So I invited him to do this with me and we publicise it, actually. Anybody could attend, but it was mainly my friends who came [laughs]. A lot of the people who attended were theatre people. It was really interesting because actually working through these exercises because the approach that he took was very much speaking from a visual arts kind of sensibility. Even though he was working on words and sounds, which kind of have also a very theatrical kind of dimension, there was much less of what theatre workshops tend to focus on. Which often are about the interpretation of words or the meaning making, whereas this one was much more about the almost visual qualities of it, how they would appear in the space for instance. The theatre people who took part were actually actually saying afterwards some of the exercises were familiar to us, but we felt that they were framed very differently to how we are used to framing them. There was much more concern about space and spatiality of words and sculptural qualities of words. I've done a couple more of these reenactments and if COVID hadn't happened, we had a plan for him to also work with my students. But because he's now a bit older, I don't want to put him at risk to invite him in. He's he's a brilliant person to do that with. He approached his teaching practice very much as a conceptual practice and so it was much easier to reconstruct what it is that he did. I've always been intrigued by this sort of hidden history of of pedagogy within the emergence of experimental art. You read a lot about John Cage and his teaching at the New School in New York. I often think, what did he do with the students? What did they actually do? I mean, there's some accounts of the students about stuff that they would improvise on in class. But I've been often intrigued to learn more and it is actually only a little bit written about about that. What did he actually do with these students in class? Beuys has also been a very much a kind of teacher figure as well as an artist. But there were others, too, Suzanne Lacy and Allan Kaprow at CalArts. A lot of the kind of canonical artists were also teachers. Some of them for instance Kaprow wrote about education. Beuys considered education as part of his key part of his practice. Others may be less pronounced.

| | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| | [[File:CivicYouth Strategy.jpg|thumb|Notes by Suzanne Lacy on the ongoing civic engagement in Oakland and the Oakland Youth Policy Initiative. Image courtesy of Suzanne Lacy.]] |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| '''Anja Groten''': I was also wondering about documentation. Within the collective, I work with there is an implicit agreement that we want to share what is happening in a workshop with others, who may not partake. But the question of documentation has never really been resolved. What's a good way to do it? As you say as well, while you come up with a class or a workshop, you work towards that moment. The workshop is shaped also in the actual encounter with people and materials and space. But then it's also a pity we don't have more documentations of these situations. They travel through time as stories of witnesses maybe but it would be so great to practice and experiment with more ways of documenting that are meaningful. Obviously not just taking pictures of happy people having a great time, but to find ways of documenting that afford continuation and also discussion and reflection of these workshop practices and makes sure workshop scripts, however share or form, are preserved, taken care of. The way I do it is also usually very messy and also very ephemeral. We have a wiki where we keep a lot of workshop outlines, but also code is important to H&D workshops which often lives somewhere else. Our archive is scattered, at different place online and also offline. It's a bit overwhelming which also seems to lower the chance that someone else will pick it up some time and carry it on. | | '''AG:''' I was also wondering about how you document workshops. As you said yourself, even though you come up with the initial class or workshop, it is to a large extent shaped in the actual encounter with the people, materials, and space itself. It is obviously not so interesting nor meaningful to just take pictures of people having a great time. So what are ways of documenting that afford a continuation of whatever is happening in these short workshop encounters, and which allow for retrospective discussion and reflection of these workshop practices? The way I document workshops is usually very messy. Our workshop archive is scattered in different places, online and as well as offline. |

| We sometimes compare workshop scripts with protocols and sometimes work with reenactments of what a computer would do – translating something that happens in your machine into physical space. Is there a parallel with scores? I am not very familiar with scores it makes me think of protocols or algorithms. It's it's not a recording or a replica of a situation, but it's sort of anticipating on it. It’s a great way of thinking about documentation, as something that is not only about looking back, but really towards continuation and activation in the future. But scores I have seen look rather abstracts. Is there a practice within the field you're familiar with Of annotating scores in a way that makes them more contextual?

| | I was wondering, sometimes we compare workshop scripts with protocols and orchestrate [[#Scripting_Workshops|physical re-enactments]] of what a computer would do, translating something that happens in your machine into a physical space. I am not very familiar with scoring practice but what I do know makes me think of protocols or algorithms. It's not a recording or a replica of a situation, but it sort of anticipates it, sets conditions. I wonder if it could help us think about documentation as something that is not only about looking back, but in fact geared toward continuation and activation in the future. |

|

| |

|

|

'''Heike Roms''': That's a good question. I mean, there's lots of scoring practices in visual arts, you know, through happenings and Fluxus through the sixties. From the sixties onwards, it's become a really common practice. In performance art and dance, they have really extensive scoring practices. The indeterminacy of the score is part of what the art practice is about. You give somebody a score and it could be interpreted in a hundred different ways. That's why it becomes interesting to consider where is the artwork located? Is it the score? Is it the realization of the score? To the point where a Fluxus score wouldn't even tell you how many people have to do it or whether they know who they should be or so it's the very indeterminacy of the action. That's the interesting thing about the Fluxus score. Different is maybe the musical score, which is maybe more prescriptive. There's again, a bit of leeway of interpretation, but there's probably more prescription in the musical score than there is in a in a Fluxus score, which makes the question of authorship, maybe in the musical score also complicated. Traditionally, we think of the author of the score as the author of the work, and because the level of interpretation and indeterminacy is sort of restricted. But there's been lots of experimentations done since, in scoring practices and people have used scores and the relationship between the score and the event that it might anticipate or the event that it might generate. There's lots of really interesting artists who play with scoring practices. I'm not sure about annotation, but there was this project that Hans Ulrich Obrist did a few years ago. It was called "Do It" and invited artists to write scores. He invited artists who don't normally have a scoring practice. One of the ideas of the project was to invite people to enact the score and then to place documentation of that enactment online so that you could see you could see the score and also have a multitude of different kinds of documentation of the different kind of possibilities of the enactment of that score.

| | '''HR:''' From the sixties onwards, through Happenings and Fluxus, practices of scoring actions have become a common device in visual arts. And in performance art and dance, very extensive scoring practices have emerged. The indeterminacy of the score or instruction is partly what interests artists. You give somebody a score, and it could be interpreted in a hundred different ways. That's why it is interesting to consider where the artwork is located in these practices. Is the score the artwork? Is it the realization of the score the artwork? A Fluxus score, for instance, wouldn't even tell you how many people have to carry it out. Such a score could be about the very indeterminacy of an action. |

|

| |

|

|

'''Anja Groten''': I am now working on this publication trying to think through this question: How to publish something like a workshop or a workshop script, which is an interesting graphic design object because it's very unresolved and it's very spontaneous and it's actually not a precious object and never up to date. And that's how it functions. But how to publish something like this in a meaningful way? For instance, pictures of workshop situations can help to contextualize something like the score or workshop script. It helps to see people being committed to the score. You cannot just give the score to someone and then expect them to know what they have to do and how to be excited about it. You need that activation moment and how to, how to generate that I think gets a whole own practice in a way. But these snapshots of people is nothing necessarily you want to print in a book.

| | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| | [[File:RobertFilliou.jpg|thumb|Fluxus artist Robert Filliou published the book "Teaching and Learning as Performings Arts" in 1979. The book is designed in a workbook manner, leaving space for annotation in the middle of the page https://monoskop.org/images/9/93/Robert_Filliou_Teaching_and_Learning_as_Performing_Arts.pdf]] |

| | </div> |

|

| |

|

| '''Heike Roms''': It brings us back to the differences – that there are different kinds of workshops. There are also different kinds of scores. There's those that are meant to be indeterminate and meant to generating lots of different kinds of responses, and every response is justified and equally valid. Sometimes having visual documentation can also prescribe someone. If you see a score and you already see somebody enacting it, you think, well, that's the way to do it. It takes a little bit of your agency away. Unless you do it like I think the DIY do it project, try to do it, just give me multiple enactments so that you can encourage people to say, actually, look, these are already five different versions, so go and do your own. But then there are workshops where the knowledge that is passed on is much more prescribed. So there are scores where what is being described as much more prescribed and people want them to be enacted in a particular kind of way, particularly often in pedagogical contexts. Do you want the exercise to be landing in a particular kind of way? Because you want the students to have a particular kind of learning experience. I'll have to kind of identify the learning outcomes. There are different scoring practices and so there are different kind of documentation practices that might be kind of suitable for different kinds of scoring practices. I would always say it's always the doing that's interesting. So we will never probably reach a point where we can say, this is a, this is the documentation practices, this is the skill in practice. It's all about the the kind of the finding process and the kind of rationalization and reflexivity that you go through in this process that I find exciting and interesting. Trying to find one and failing maybe, but, you know, try to try to address it in some sort of a way.

| | Traditionally, we think of the author of the score as the author of the work, such as in musical compositions, for example. But more recently, we are seeing much more experimentation with scoring practices, and with the relationship between the score and the event or action that it might anticipate or generate. A few years ago Hans Ulrich Obrist did a large-scale curatorial project called “do it,”<ref> “do it (2013-) curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist,” Independent Curators International, https://curatorsintl.org/exhibitions/18072-do-it-2013.</ref> which invited artists who don't normally have a scoring practice to write their own scores or instructions. People were invited to enact these score and then upload documentation of the enactment online so that you could see the score, as well as a multitude of different kinds of documentation of the different kinds of outcomes produced by their enactments. |

|

| |

|

| And this is always what I feel in practice-based PhD projects in particular. It’s just as often interesting to say, look at this person and how they struggled through these issues and the kind of solutions that they came up with, even if they're only temporary or insufficient or whatever.

| | '''AG:''' I am trying to think through the question of how to publish something like a workshop or a workshop script. In my view it can be an interesting graphic design object because it's very unresolved, very spontaneous, it's actually not a precious object, and it’s never up to date. These criteria are significant for it to function. But how do we publish something like that in a meaningful way? For instance, pictures of workshop situations can help to contextualize something like a score or workshop script. You cannot just give the score to someone and expect them to know what they have to do and how to be excited about it. You need that activation moment and know-how too. But including snapshots of people doing things is not necessarily interesting to print in a book. |

| [And then we went on sharing references, Heike showed me some books in the camera] :

[add bibliographies]

| |

|

| |

|

| —— New subject ——

| | '''HR:''' It brings us back to the fact that there are different kinds of workshops and different kinds of scores. There are those that are meant to be indeterminate and generate lots of different kinds of responses. Every response is justified and equally valid. Sometimes visual documentation can therefore be too prescriptive. If you see a score and somebody enacting it, you might think, well, that's the only way to do it. It takes a little bit of your agency away. Unless you do it like the DIY “Do It” project, where you provide the documentation of multiple enactments so you encourage people to try their own response by showing them five different versions. But then there are also scores where which are much more prescriptive, and people want them to be enacted in a particular kind of way, particularly often in pedagogical contexts. Do you want the exercise to land in a particular way, because you want the students to have a particular kind of learning experience? There are different scoring practices, different ways to shape an instruction, and similarly there are different kinds of documentation practices that might be suitable. Yet, I would say that it's the “doing,” the [[#Conceptual_Speed_Dating|activation and interpretation of a score]], that's interesting. It's all about the finding process and the kind of rationalization and reflexivity that you go through in this process that I find exciting. It’s often just as interesting to look at how a person struggled through finding a response to a a score or instruction than the response itself. |

|

| |

| '''Anja Groten''': You also teach workshops for children? What are they about? | |

|

| |

|

|

'''Heike Roms''': I do performance work with children. I've also started writing about the work that Kaprow and Fluxus did with children in the sixties. I work closely with an artist in Hamburg, Sybilla Peters, who runs a theatre for children. She calls it a theater of research.

| | '''AG:''' You also teach workshops for children. What are they about? |

| [https://www.thisisliveart.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/uploads/documents/SYBILLE_TOOLKIT_WEB.pdf]

| |

|

| |

|

| The philosophy of the place is that research is something that artists do and it's something that children do and it's something that scholars do. So we all are involved in research and we all work on research together. She brings these projects together around a particular theme that is often of particular interest to the children you research together with. I did several projects with her where I get often invited as somebody who has knowledge of some art historical stuff. The last workshop we did was on on destruction, which is a really big thing for children. Because they're often told they have destructive behavior or are destructive. | | '''HR:''' I have been involved in some performance work with children through my collaboration with the artist Sibylle Peters, who runs a theater for children in Hamburg, the FundusTheater/ Forschungstheater. Sibylle calls it a “theatre of research”.<ref> Sibylle Peters, performing research: How to conduct research projects with kids and adults using Live Art strategies, (London: Live Art Development Agency, 2017), https://www.thisisliveart.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/uploads/documents/SYBILLE_TOOLKIT_WEB.pdf.</ref> The philosophy is that research is something that brings artists, children and scholars together, as it's something that artists do, it's something that children do, and it's something that scholars do. She devises projects around different themes which are of particular interest to the children she researches with and are often driven by their desires, such as ‘I want to be rich’, which led to an examination of the nature of money and the founding of a children’s bank with its own micro-currency in Hamburg. I did several projects with Sabine, where I was invited for my knowledge of performance art history. The last project we did was, Kaputt – The Academy of Destruction at Tate Modern in 2017. Destruction is a really big subject for children, because they're often told they are destructive or have destructive behavior. |

| | We worked with children who were diagnosed with behavioral issues, who showed what was deemed destructive behavior in class, or who were really interested in watching cartoons where things get destroyed. Kids see and hear about destruction all the time, for example the destruction of the environment. When we were doing the project in London, seventy-two people had recently died in the Grenfell Tower fire as a result of negligence.<ref> “Grenfell Tower fire,” Wikipedia, last modified October 10, 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grenfell_Tower_fire.</ref> It was close to where the children we worked with came from, and it was very present in their minds. But there's no real outlet for children to explore their fears about destruction, but also their interests and pleasures in destructiveness and their destructive fantasies. We worked with the children on the notion of destruction for a week. We were all considered equal experts on the subject, and we all shared our expertise. The kids gave talks, for example about destruction in comics and animation. I gave a talk on destruction and art. Sybille has done lots of these kinds of projects, which I occasionally get invited to participate in and work on issues that overlap with the histories of art. Inspired by our work together, I have recently begun to research the participation of children in the history of avant-garde art, especially in the performance practices of Happenings and Fluxus. |

|

| |

|

| We worked with children who were diagnosed with behavioral issues who show destructive behavior in class or also kids are often really interested in kind of watching cartoons where things get destroyed. They have a real interest in destruction. They see and hear about environmental destruction .When we were doing the project in London, this big high rise building had just burnt down and lots of people had died. It was a part of the community where these children came from. There's no real outlet for children to explore their destructive fantasies, their interest and the fears about destruction. We worked with the children on this notion of destruction for a week. But we were all experts together and we all shared our expertise. So the kids would do talks about destruction and comic books, and I would do a talk about destruction and art.

| | <div class="visual-footnote img"> |

| | [[File:Pages-from-SYBILLE_TOOLKIT_WEB.jpg|thumb|Page from: Sibylle Peters, performing research: How to conduct research projects with kids and adults using Live Art strategies, (London: Live Art Development Agency, 2017), https://www.thisisliveart.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/uploads/documents/SYBILLE_TOOLKIT_WEB.pdf.]]</div> |

|

| |

|

| '''

Anja Groten''': That sounds amazing. | | What is important to Sibylle as well is this idea of the workshop as a space for [[#Open-source_Parenting|equitable relationships]]. She takes seriously what the kids bring to the discussion. And it's always about rethinking and [[#Am_I_a_hacker_now?|reshaping the adult-kid relationships]]. We will be working together again in September 2022 on the occasion of the opening of a new building for the Fundus Theater in Hamburg. For that event I am currently working on some research that looks at child activism in the sixties, especially the involvement of children in the American Civil Rights movement, and how that intersected with children's participation in experimental art projects at the time. How children were trained for their participation in protest or art with the help of workshops will be a major aspect of this research too. |

|

| |

|

| '''

Heike Roms''': They've also done projects around piracy. There was a big case a few years ago when some Somali pirates were being tried on trial in Hamburg because the main marine kind of court is in Hamburg. And and, of course, pirates are something that kids are really interested in. And so Sybille did a project around what is a pirate? I worked with a couple of Somali pirates. The kids decided on the questions for the interview, and then they interviewed the Somali pirates. For instance: Have you ever killed somebody? It was pretty extraordinary.

| |

|

| |

|

| They did a project on money, what is money and it is money produced. They found a children's bank that produced money that they could then use in the neighborhood. It was all about what is money. What does money mean? Why do we have money or no money? What can money buy? And so they actually managed to persuade a number of businesses in the neighborhood of the theater to buy into this local currency. Lots of projects that she does and I get invited occasionally to come and work on kind of issues that also overlap with histories of art.

| | <small> |

| | | '''Heike Roms''' is Professor in Theater and Performance at the University of Exeter, UK. Her research is interested in the history and historiography of performance art in the 1960s and 1970s, especially in the context of the UK. She is currently working on a project on performance art’s pedagogical histories and the development of performance in the context of British art schools. |

| '''

Anja Groten''': We recently started thinking about how can we develop workshops that have different sort of levels of participation? Last weekend we hosted an, intergenerational workshop with kids also and their parents about how the Internet works. And we made a sort of a little – a mini Internet, consisting of a wifi module that is powered with a little solar panel. We could put little hints and clues this module. We used it to create a scavenger hunt, which we designed together with the kids. It was a shared effort between kids and grownups. We were designing the scavenger hunt together. Everyone would contribute on different levels.

| | </small> |

| | | </div> |

|

'''Heike Roms''': That's really important to Sybille as well. And again, it comes back to this idea of the workshop as a space of kind of potential equitable wholeness. She always kind of tries to take seriously what the kids bring to this. And it's always about adult-kid relationships. We are doing something together in September that looks at child activism – children as political activists. I started looking into the history of activism in the sixties and children's activism and how that intersected with children's participation in experimental art projects.

| |

| | |

| [now about references again]

| |

| | |

| | |

| Heike Roms is Professor in Theatre and Performance at the University of Exeter, UK. Her research is interested in the history and historiography of performance art in the 1960s and 1970s, especially in the context of the UK. She is currently working on a project on performance art´s pedagogical histories and the development of performance in the context of British art schools.

| |

In her talk "The Workshop as an Emancipatory Mediation Method of Resistant Practices" political activist Hanna Poddig referred to the

discussion scores that are also common in Consensus Decision-making practices

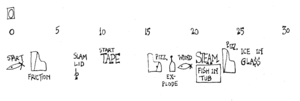

"A section of Water Walk," score by John Cage

Notes by Suzanne Lacy on the ongoing civic engagement in Oakland and the Oakland Youth Policy Initiative. Image courtesy of Suzanne Lacy.

Workshop Histories and Practices

In conversation with Heike Roms

Anja Groten: In May 2021 I participated in an online conference titled “The Workshop as Artistic-Political Format,” organized by Institute for Cultural Inquiry in Berlin.[1] The conference drew together practitioners from various fields of interests, including choreographers, dancers, theater makers, artists, scholars, musicians, and activists who reflected on “workshop” as a format, site, and phenomenon from their own perspectives. Heike, you gave the presentation "The Changing Fate of the Workshop and the Emergence of Live Art,” which particularly resonated with me.

Heike Roms: I came to the topic of workshops because in my work I look at the emergence of performance art in the sixties and seventies. I became interested in particular in the emergence of performance art within art educational contexts, in a conceptualization of a pedagogy of performance. I've read your chapter on “Workshop Production,”[2] which I really enjoyed. Some of the research you've done is helpful to me because I too have found that there's actually very little written about the workshop as a practice. That is, people have written about specific workshops so you can find material on workshops given by a particular artist. But there is little reflection on the workshop as a format, as a genre, as a site, as whatever we might call it. That surprised me, given that it's sort of ubiquitous in practice. There are books on performance laboratories, for example, and there is a connected history between the workshop and labs, the studio space, and rehearsals as a format. But there is very little on the workshop, certainly within performance studies or art history discourse, so I became intrigued by this ubiquitous form that remains largely unexamined. It's great that through the work of Kai van Eikels and the 2021 conference he co-organized there's a new kind of attention being paid to it, through your work as well. But there is not enough available about the history of the workshop to help us understand at what point this flip occurred from considering the workshop as an actual physical site to approaching the workshop as an event format. You write about this as well. The two meanings, of course, continued to exist in parallel, particularly in the context of art schools. But at what point did the workshop become an event, a time-based learning experience, as well as a site of making—a Werkstatt? I don't know how and when that occurred. My suspicion is that it was sometime around the fifties and sixties.

AG: There is the The Journal of Educational Sociology that was published in 1951 and refers to the first organized professional education activity under the name of a workshop. It took place at Ohio State University in 1936.[3] I remember you were talking about the relation between the occurrence of workshops and the emergence of a certain resistance toward the steady structures of art schools in the fifties and sixties in the UK—a resistance to legitimized knowledge practices and skills. Art students wanted to rid themselves of a certain authority of disciplines or disciplined learning and instead wanted to take things into their own hands.

HR: In the specific history I looked at, which is that of Cardiff College of Art, I found that there is a confluence between the workshop and two emancipatory movements. First was the move toward the workshop as a learning format through the impetus of the Bauhaus, which in the 1960s developed a huge impact on art schools across the UK. Traditionally people weren’t really talking about workshops as sites of making in the context of art schools; the workshop was the place of the plumber or the blacksmith, while artists worked in ateliers or studios. I think that the idea of the workshop as a place of making was introduced to the art school through the Bauhaus philosophy, which was a vehicle for the emancipation of art education. All of a sudden art was being approached in the same way as other practices of making were being approached. No longer did we have the sculpture atelier or the drawing room. Now there were ceramics workshops, metal workshops, printmaking workshops but also painting workshops and sculpture workshops (or ‘2D’ and ‘3D’ workshops as they were often called at the time). This move introduced a different kind of art making.

This change that occurred in art schools in the UK in the sixties through a new approach to art education known as ‘Basic Design’ was very much driven by the reception of the Bauhaus approach and in particular Joseph Itten’s Vorkurs (preliminary course). Workshop production was seen as a new, more emancipatory form of art making. It came out of the experiences of the Second World War and the desire to give art students a different sort of experience—one that connected them to the contemporary world rather than traditional skills training and that aimed to overcome the distinction between art, craft and design.

The second shift is where performance comes in in the 1960s. Teachers and students saying: We don't want all of that material making in the workshop. We want to make something that's ephemeral and that's collective and that's participatory. We don't want to be hammering away all day in the workshop. Instead we do this other thing where we get together and we make something that’s not actually about producing any objects, and we'll call that a workshop as well. That's the event-based rather than space-based concept of the workshop.

In dance, people were already talking about workshops as events in the fifties. I don't know when the shift occurred from the workshop as a site toward the more ephemeral understanding of the workshop as event, how that happened, but it's interesting because what motivated the artists in the sixties that I have been looking at—and they explicitly say so in their notes—was that this move toward the ephemeral was about searching for more equitable relationships that do away with the teacher-student division. That division had been further cemented by the remains of the Bauhaus philosophy and its celebration of mastery. I think that was one of the key shifts toward this more ephemeral meaning of the workshop. It was no longer about a master passing on knowledge to their students. It became about collective making. And everybody took collective charge and responsibility for that making. The educators on whom I've done research actually say that they wanted to get away from producing objects toward collective action. But, as you say, the workshop can very easily be co-opted like so much of the sixties was. Was that the last hurrah of collectivism? Or was it actually what lay the groundwork for the entry of neoliberalism into education as we now know it?

AG: I myself am wondering whether organizing workshops can generally be considered an emancipatory practice at all? Perhaps there cannot or should not be a general answer to this question. At the school where I work as an educator, some argue the educational system builds upon rather precarious labor conditions, where everyone works as a self-employed freelancer. Simultaneously, more and more workshops are being organized, which at times can clutter the education. Students are supposed to self-initiate and self-organize as well. They often resort to organizing workshops for each other. In my view, such conditions sometimes also show the limits of what can be accomplished with workshops. I think it's important to have more discussions about the workshop as a format and its implications for the learning economy. How to speak about and practice workshops in a way that still allows us to do the things we want to do, whilst also paying critical attention to the undesirable conditions it is intermingled with.

How was it for you? Did the invitation to the conference lead you to take a deeper look at the phenomenon of the workshop? Or were you already busy with it?

HR: Yes, it would be fair to say it led to a deeper engagement with the notion of the workshop. I had been working on this material before and I've written about it too. But I had never really paid attention to the frequency of the word ‘workshop’ in the material I had researched until the invitation came to speak at the conference. It was then that I realized that the workshop is a really productive format to be talking about.

I wrote a paper on this before in which I talked about the idea that artists and performance educators in the sixties and seventies in the UK were creating events as a kind of parallel institution. These events aimed to serve the function of an art school without replicating its hierarchical structures. This was the case in Cardiff, but also in other places in the UK such as Leeds College of Art. I was grateful that I was invited to think more about this by the conference. I looked at my examples, and it is specifically “the workshop as event” that emerged as a kind of parallel institution at the time. It wasn't really the performances these teachers and students went on to make together, but the workshop as a learning format that I think they clustered all their ideas around.

AG: I stumbled upon the conference last minute and wasn't aware of this whole community of performance artists and live arts who consider the workshop as an artistic medium. It's also interesting that the workshop, because of its ambiguity, manages to converge all these different worlds and unveil commonalities between them. For instance a policeman[4] speaking about their conflict resolution workshops, and the activist who learns about tying themselves to a tree and how to negotiate with the police while doing so [5]. Both speaking about the same sort of thing at the same conference from an entirely different vantage point.

You emphasized that a lot of the artists you researched were also educators. It was great to hear that engaged with in such an explicit manner. I don’t often hear about how the practices of artists and designers continue to evolve within particular educational environments, after they have completed their studies too. I find that many great artists and designers are also teachers and I personally don’t draw a harsh distinction between being an educator and being a designer. The practices go hand in hand. But I found that there are not many records of the teaching practices of artists and designers. Another thing from your talk that really stayed with me was your re-enactment of a workshop. You showed some pictures and I found them so interesting and also funny. In your re-enactment, you imagined through physical exercises what the workshop might have looked like. You referred to one specific artist educator, whose name I don’t recall.

HR: His name is John Gingell, and he is not particularly well known. I never met him in person, as he had already passed away by the time I became interested in his work. He had a sculptural practice, and a few of his public artworks are still on view in Cardiff, and some of this work has been exhibited in London. But really he was an educator. That was his main practice. He formed and shaped generations of art students. He was not the type of person to write manifestos, or write a lot in general, but I've been very fortunate because his family has allowed me to look at all of his materials, which are now kept in the attic of one of his daughters. He didn't leave a written philosophy of teaching or anything like that, just really random notes or little statements that he put together for the art school in order to justify what he was doing, or presentation outlines and things like that.

I didn't re-enact any of his workshops because they were very sketchily documented. He was not somebody who kept a particularly developed documentation or scoring practice. If I think about my own teaching, I don't either. When I enter a classroom, I often just jot down some notes on the exercises I want to do. They're just little prompts, which aren’t accompanied with much explanation. In years to come, if somebody were to look at my teaching notes, they too wouldn’t be able to make much sense of what I was doing in the classroom. I don't think that's unusual. Anyway, I have contact with one of Gingell’s students from the late 1960s, the artist John Danvers, who also taught at the art school for a number of years in the seventies. He was very influenced by John Cage, so his own artistic practice was already very score-based. When he became a teacher his teaching practice was very well documented. He documented the exercises alongside photos of the students doing the exercises. He has quite substantive documentation on the courses he taught at Cardiff.