Cooperative gaming

Learning about complex eco-systems with Phylo(mon)

I serve as vice president of the board for Prototype PGH. I am interested in community building and I organize a Code and Coffee group within the space. I learned about Prototype PGH through a friend and was interested in maker/hackerspaces in general. My interest was piqued because the space focuses on gender and racial equity, which is unique in Pittsburgh. One of our community agreements is “Alone we know a little; together we know a lot.” Our members write the programs and we try to encourage everyone to share what they know. It’s important to have spaces like this that are run and led by people who do not generally get the opportunities to practice these skills. The name of our space is intended to remind people that it’s OK to try and try again. This is not a space for perfection, rather a space to learn and refine. I have worked in I.T. for a decade and have mostly been self-taught. I decided to ‘“formalize” my knowledge by getting a degree in software engineering last year. I think the greatest challenges of being a programmer are not technical, but social. I question the various business models being used in the field and the ethical concerns that rise up as a result. I am particularly concerned about user data and how it is often privatized. I’ve read critiques from scholars such as Evgeny Morozov, Ruha Benjamin, Shoshana Zuboff, and Kate Crawford, to name a few. These authors investigate and question practices around ownership, labor, privacy, and the commons. This led me to the world of free and open source software, which I have found to be more actively engaged with these questions. I enjoy reading about and exploring alternative economic and technological systems that aim to provide more equity.

In my personal life, I enjoy running free and open-source software wherever possible. I love the transparency that is baked into these systems since they allow me to learn and make modifications if I so choose. I consider myself to be a late bloomer when it comes to free and open source technology. My interest grew from curiosity and experimentation, but I did not feel strongly about it. It was only when I learned of the broader context and social issues that surrounded it that I turned toward it more fully. Finding that internal motivator is key to reorienting oneself toward it, and that motivator is different for everyone.

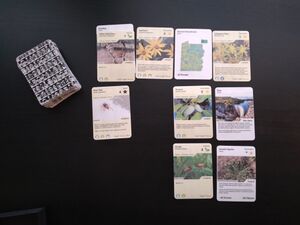

I discovered the Phylo(mon) Project while exploring how other fields employ free and open source types of licensing for their projects. This project was born out of the phrase “Kids know more about Pokemon creatures than they do about real creatures.” The aim of the game is to have real creatures and plants represented on cards. Because having knowledge of the cards is key to winning the game, kids learn about their local environment while playing it.

I have long had an interest in games and game design. I think games can teach us a lot about the world and help us to develop the skills we need to survive, especially in the context of climate change. Cooperative games in particular build the same skills that can be used to solve real life problems, empowering us through play. I loved the concept of the Phylo(mon) Project and since they license the mechanics under a Creative Commons License Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, I was interested in morphing the game into a cooperative variant.

With the help of software engineer Charlie Koch, I reworked the core card design and mechanics to create a cooperative version. To face our climate change problems, we as a species must learn to work together, understand our local ecological contexts, and figure out how that can affect the global context. Our hope in creating the free and open source card creator is that people will be inspired by each other’s cards and decks to go out and perform the necessary actions needed to deal with negative environmental issues occurring in their communities. We wanted to make it as easy as possible to create cards for one’s community as well as make our software update instantaneously so that creators can get instant visual feedback on the cards as they are adding information to them. Our software design takes into account privacy and portability in that the entire application is run locally in the browser. People can use it to make a deck or even single cards and export the files to share with others. We initially developed the software for use in a classroom or group. The idea was to have participants create single or sets of cards and the facilitator put the deck together.

I related the actual creation of the deck using our tool and programming methods to meaningful gamification. The concept of gamification was developed by Scott Nicholson, professor of Game Design and Development at Wilfrid Laurier University in Brantford, Ontario. It is the application of game elements to a non-game context. Most gamification focuses on extrinsic rewards such as badges, leaderboards, awards, and points. Meaningful gamification focuses on designing principles that increase one’s sense of relatedness, autonomy, and mastery. Our tool and educational workshop around Phylo tries to facilitate play (creative and unexpected use of the card-making tool), engagement, and reflection.

The workshop makes use of two different concepts: a game and a metagame. The game involves playing the deck to see how many points the player can get. The metagame involves making a deck, conversing with others about it, and sharing the decks with other communities. The game has to simplify the complex ecological systems, therefore little deep learning of the subject is possible, but it does encourage tangential learning because it leads you to ask questions about how these creatures actually function in the world. The metagame promotes deeper knowledge of the ecosystem since the maker must find a way to map these complex ecological systems onto the structure of the game. The option to share the deck with communities around the world allows users to reflect and engage with others and gives them a chance to learn how others would solve the same issues. In this way, the metagame meaningfully gamifies the learning of ecosystems.

I enjoyed the process of developing the script for the H&D Summer Academy in 2021. It pushed me to write as clearly and succinctly as I could while trying to incorporate principles of meaningful gamification. It was great to see participants from other nodes use the card tool in unexpected ways, such as inventing new species, stories, and rules. After sharing this deck, it prompted our node in Pittsburgh to reflect on our card game and how else it might be modified and iterated upon. For this iteration of the game, I think that the distributed format worked well. If the workshop had taken place in just one location, I would have probably instructed participants to make several decks with different themes, such as rewilding and bioremediation, flora and fauna, or urban issues. That way, each group would be able to focus on their topic and share the knowledge they learned with others in the same community.