Mud Batteries

Solarpunks Intergenerational Workshops—Vienna edition

Olivia Jaques and Stefanie Wuschitz of Mz* Baltazar's Lab organized an open-air workshop for children and their caretakers to make mud batteries. Mud batteries are batteries that harvest electrons generated by anaerobic microbes in the mud—it’s almost as if the microbes inhale dirt to exhale electricity. During the workshop each child and their caretaker built their own mud battery. We had prepared all the necessary parts to build the mud batteries beforehand.

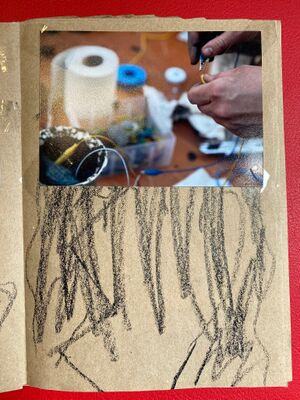

To make one mud battery you need:

- Graphite (crayons or pens)

- Two wires with clamps (alligator clips)

- Two jars (we used ceramic vessels the size of large drinking glasses)

- Some stinky mud (leaves, branches, and stones should be removed so only fine-grained mud remains)

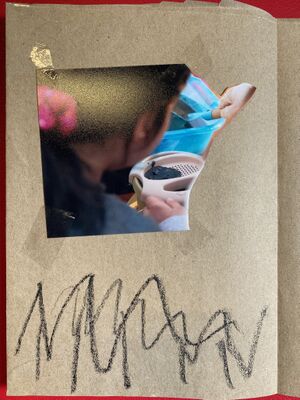

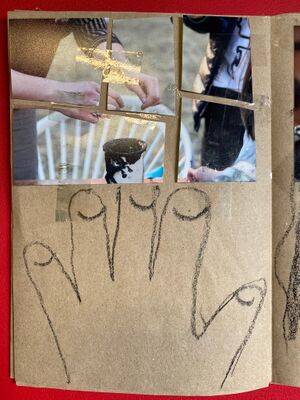

To introduce the workshop we talked about electricity and its role in society, and the environment. We asked questions such as: Why do we care about the environment and why should we protect it? The kids, with our help, sieved the mud and filled it into small containers. We put one piece of graphite into each jar and attached two wires––one as anode and another as cathode. Then we waited while the microbes rearranged and aligned themselves with the electrical polarity we created. After some time had passed, we arranged all the mud batteries in a line to maximize their power and measured the total voltage. The voltage was extremely low, which prompted a conversation in which we speculated on how we could shift toward greener and more respectful forms of power consumption. The kids enjoyed playing with the mud and the caretakers enjoyed exploring alternative energy sources. Building the circuit to measure incoming voltage was a messy business, but the process felt exciting and adventurous, largely because the kids were not usually permitted to play with mud or electricity.

Overall, we were happy with the result of the workshop, and we had an unusually high number of first-time participants. The kids were very excited and participated enthusiastically in the workshop. This gave the caretakers the opportunity to go upstairs, prepare some food, and bring it out to share with everyone. This way, the workshop became a picnic as well. The next time we run the workshop we would like to focus more attention on involving the caretakers to build something as a shared effort. It was a very nice experience, nonetheless. The workshop and picnic enabled us get to know each other as neighbors. Weeks later, kids who participated were coming up to us and saying hello when they saw me on the street.

The following exchange is a conversation between Olivia and Stefanie in which they reflect on some of the subjects breached during the Solarpunk collaborative trajectory.

Stefanie Wuschitz: When Anja Groten and Loes Bogers asked our collective, Mz* Baltazar's Lab, to collaborate with H&D, I knew this was going to be a wonderful project! I am very inspired by the ethical approach they take on all their projects. When Mz* Baltazar's Lab met with the other nodes in the network––in Pittsburg and Amsterdam––it clicked, and in the months that followed we all got to know each other better, the initiators of the labs, and the organizers in their communities. During regular online exchange we came to learn that we were all struggling with similar issues in our work.

Olivia Jaques: Some struggles seemed to be universal, such as the struggle of trying to balance raising a kid with working as an artist. Other struggles seemed to be local and context-based, such as the issue of racism in the neighborhood. Mz* Baltazar's Lab, for example, is located in the 20th district in Vienna, Austria’s capital. The lab’s direct surroundings are buzzing with different languages and cultures. Housing here is more affordable than in other areas of Vienna. You find low income households here as well as various grassroots initiatives and artists living in the area. The kids hanging out at the playground are mostly raised bilingual. When communities stay within their bubbles, it’s more difficult to create situations of exchange. Mz* Baltazar's Lab feels quite detached from the neighborhood in some senses; but then again, it’s serves as an important home for its queer, feminist, tech/hacker/media-savvy community. We don't have to fight for gender-inclusive language or against patriarchal norms within our bubble, friction only occurs when we step outside our comfort zone. Hence, our code of conduct can be understood as an exercise, as reproductive labor. It is something that we need to co-create together, and it must grow and shift with time.

In particular, I remember the discussions we had after the presentation on codes of conduct, in which we looked at the different codes from each lab. Seeing the variety in content really helped me to grasp the local contexts of each lab, their complexities, and their significance to each of their communities.. What do you think, Stefanie? Do you feel Hackers & Designers, Prototype, and Mz* Baltazar's Lab play different roles or perform different functions to their specific environments?

SW: I think the artistic activities we came up with respond directly to our specific cultural contexts. It was motivating for me to see that Hackers & Designers and Prototype had already transformed their struggles into new formats. The ones that inspired me most were workshops targeted at very specific groups like “hacker moms” from minority groups.

OJ: I remember when you asked me if I wanted to conduct the mud battery workshop with you. Back then, in March 2022, we were thinking of using the Mz* Baltazar's Lab space. It is basically a white cube with two big window displays, allowing passersby to look inside if they feel too shy to enter. Across the street a small park is squeezed in between two building blocks, a kindergarten, and a playground. It was actually a coincidence that we changed the original plan of hosting the mud workshop in the lab to a guerilla-style open-air workshop in the park. This felt like a pretty unconventional move for Mz* Baltazar's Lab, and yet at the same time it suited us well, as we both have a strong affection for community and participatory art. I do hope we can continue with this approach. For me, it is really important to think of art as a means to build bridges between different communities. The format of the mud workshop has a lot of potential in this sense. We got such a positive reaction from the kids; they were intrigued by what was happening and were very keen to participate and experiment with us. To demonstrate how electricity works, you brought a battery, wires with clamps, and a light bulb. To the kids, this may as well have been the beginnings of a magic trick!

The setting of the workshop opened up the possibility of trying something unusual in our usual surroundings––this was very exciting for the kids. Most of them were hanging out at the playground by themselves and they approached us quite independently. The age range turned out to be quite different from what we originally had in mind; the youngest were around three years old and the oldest were around ten. Our initial intention was to organize the workshop for kindergarten children who––or so we thought––would like the idea of sifting the mud and shoveling it into jars. But as the older neighborhood children grew curious and joined in, they quickly took over the mud sifting, and with it, changed the dynamic of the workshop. With their advanced motor skills and knowledge, the older children were able to teach the younger ones; conversely this meant that the younger ones gained less hands-on-experience. The caretakers stood back, perhaps to give space to the kids, or perhaps because they were happy to get a break from parenting.

Referring to the adults as "caregivers” is, I must confess, an optimistic statement––it comes with a certain agenda. I resonate strongly with the label myself, and view myself more generally as a parent than I do a “mom.” This must be due to my specific situation. Today, kids grow up within many different family constellations; society has to get used to it. The normative idea of a family as consisting of a mother, father, and child is only one possibility among many. How would you describe the situation in Vienna when it comes to caretaking?

SW: Society in Austria is still quite patriarchal. It is unlikely that one would give a second thought to how caretakers could become structurally more included. Female-identified folks usually stay home with the kids, and dedicate their time entirely to care work. When the kids grow up and go to school, female caretakers go back to work in part-time positions, so that they can still pick them up from school. It is due to these part-time positions that female* citizens in Austria receive only 40 percent of the retirement that male-identified citizens receive. But of course, this is quite substantial compared to countries where there is no such thing as retirement whatsoever.

My position is a bit different. My partner works part-time to pick up our children from school. Even though this creates less financial dependency on my partner, I still find it challenging to be both a mother and a hacker. To me, hacking is an artistic practice. It means exploring tech-related and tech-caused problems, opening the black box, and demystifying tech-solutionism. But it is hard to keep up the pace that is necessary for hacking in the chunks of time I have available.

The communities I participate in value the kind of creative and critical thinking that open source culture encourages. They think of themselves as very open-minded. Yet many people who work at this intersection—of art, science, and activism—don't live with kids. In fact, every hacker in our community who became a mother dropped out sooner or later. This is not only disruptive for our community at large, but also for the individually, because it becomes harder to do art and hack by yourself at home.

Olivia Jaques is a Vienna-based artist and cultural worker. As her work spins around the relational, socio-political (feminist!), and the performative, most of her work is created through artistic collaborations. For 10+ years she has been working together with Marlies Surtmann. Since 2017 they have been running the Performatorium,a laboratory for practice-oriented research of and through performative means. In2022 they were awarded the TQW Research Affiliation, and in 2023 they will continue their work within an INTRA artistic research project together with Charlotta Ruth. As part of a transdisciplinary artistic research team Jaques is currently involved in a PEEK project at the University of Applied Arts.

Since 2016, Jaques has been associated with artasfoundation, a Swiss Foundation for Art in Conflict Regions, in which she explores how artistic collaboration across cultures can be achieved and what role artistic work can play in peace processes. Recently she has become part of Mz* Baltazar's Laboratory and is also part of the transdisciplinary artistic research team morphopoly, a PEEK project at the University of Applied Arts.

Stefanie Wuschitz works at the intersection of research, art, and technology, with a particular focus on Critical Media Practices (feminist hacking, open-source technology, peer production). She graduated in 2006 with an MFA in Transmedia Arts (University of Applied Arts Vienna). In 2008, she completed her Masters at TISCH School of the Arts at New York University and became Digital Art Fellow at Umea University in Sweden. In 2009 she founded the feminist hackerspace and art collective Mz* Baltazar's Laboratory in Vienna, and in 2014 she finished her PhD on 'Feminist Hackerspaces' at the Vienna University of Technology. She held research and Post-Doc positions at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, the Vienna University of Technology, Michigan University, Weizenbaum Institut, Universitaet der Kuenste Berlin, TU Berlin (Open Science, Berliner Hochschulprogramm DiGiTal) and is currently project leader of an FWF research project on 'Feminist Hacking. Building Circuits as an Artistic Practice' affiliated to Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. Her works have been exhibited in international venues such as Panke Galerie, Berlin;, ART|JOG 8, Yogyakarta; Bouillants, Vern-sur-Seiche; Austrian Cultural Forum, New York City; Fringe Festival, Taipei; and others.