Publishing:Making Matters Lexicon: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Manual revert Reverted |

No edit summary Tags: Manual revert Reverted |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{TOC|limit= | {{TOC|limit=3}} | ||

<div id="introduction" class="chapter chapter-introduction"> | <div id="introduction" class="chapter chapter-introduction"> | ||

Revision as of 10:56, 2 March 2022

introduction

making matters

a vocabulary for collective arts

The world today faces overwhelming ecological and social problems and the concern for material existence on earth is more pressing than ever. When looking at the field of art and design, this means that research into our relation to the world around us and the actual making of things has acquired a new urgency.[1] Making Matters asks what role visual artists and designers can play under these conditions. The book gathers a number of relevant making practices and investigates the urgency from which they arise.

One of the main departure points of Making Matters is the realization that collective action is necessary and inevitable, in society at large as well as in the field of the arts. Collective art and design practices therefore are the main focus of this book. They point to a transformation of working methods that not only shapes and changes practices but also affects artists and designers in their position and identity: from individuality and autonomy to experimental collectivity and collaboration, locally

as well as globally.

A new perspective on ‘making’ becomes apparent here. When practices shift towards collaborative making processes instead of individual products, what does ‘making’ and the production of concrete, material ‘things’ mean? Artists collaborate with non-artists and in doing so may take on other identities, such as researcher, community activist, computer hacker, or business consultant. The research done by these artists departs from the most diverse areas, from logistics and biotechnology to geology or dance. As a result, the distinction between art, design, research, and activism is dissolving. It follows that these practices may hardly be recognizable as art or design practices any longer, nor are their outcomes necessarily identifiable as artistic outcomes, let alone as specific art works. Some of these practices no longer conform to a conventional Western idea of art and art making. This book aims to identify some of their key concepts and to make their vocabularies accessible to a larger public.

The practices brought together in this book address specific ecological and social problems, sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly. All of them embrace the complexity of the various crises that we find ourselves in and try to develop ways of dealing with them. They experiment with and embody examples of new ways of living together and of

a sustainable existence on Earth with all living beings.

Material artistic practices, i.e., ways of concrete making and doing, often go hand-in-hand with

a theoretical inquiry. The textual and visual contributions in this book embody this intertwinement of conceptual and material thinking. The authors share an interest in artistic research, a relatively newly institutionalized research field that connects doing and thinking, making and theorizing, in a reciprocal exchange that does not prioritize one over the other. In artistic research, practical action (making) and theoretical reflection (thinking) go together, action and thought are inextricably linked.

Art contests the age-old dichotomy of theory and practice. Since Modernism, it has involved a constant questioning of the role of art and artist. The practices presented in this book put these questions on the table once more. They exemplify the attempt to bridge the distance between theory and practice, or even (in some cases) to obliterate the distinction between art production, critical reflection, and everyday life.

The roles of artist, curator, institution (museum, Kunsthalle, artist-run spaces, biennial, documenta) and audience may become fused in the production of art.

This development raises fundamental questions

of authorship and of the status quo of the art object and process: where is it situated and how can it be perceived or experienced? The materialization of art, its aesthetic dimension, its ‘aesthetic—felt, spatio-temporal—dimension’,[2] is acquiring new meaning and importance. In the light of the pressing challenges that we are facing on a global scale, and in the light of the critical and discursive potential of contemporary art practice, ‘making’ matters more than ever before.

how, on what ground, have the contributions

to this book been selected?

Artists collectives are at the centre of attention

in contemporary art discourse.[3] The 15th edition of the world’s leading contemporary art exhibition documenta (2022) will bring the contemporary art phenomenon of multidisciplinary collectives to a wider audience. Not only are its curators, the Indonesian ruangrupa collective, such a collective themselves; most artists invited to documenta 15 are multidisciplinary collectives, too.

This book aims to contribute to the growing body

of literature on the phenomenon of the art collective in its present-day, multidisciplinary, and hybrid form.

It aims to provide insight into the subject matter of these collective multidisciplinary practices. Most contributors are practitioners whose work falls in

the cracks between the disciplines of art, design, critical theory, research, performance, community organization, social activism, and critical engagement with technology. Even when their work is grounded in one of those disciplines, it usually encompasses at least two others. In the end, these practices and the texts in this book complicate the following questions: What is research when it is done by artists? What is ‘making’ when it is informed by critical theory and turned into activism? What is ‘technology’ when it is articulated by performance artists and in community projects? What happens when their implicit concepts, definitions, and vocabularies, which differ from mainstream understandings of those same concepts, are explicated in a specific vocabulary?

The project began with a four-year research project by our material practices workgroup into the possibility of a crossover between art, design, and technology as an alternative to the capitalist-driven concept of the ‘creative industries’ consortium.

It ended with the observation that alternative crossovers exist in the often overlooked and often overlapping fields of artistic research, artists’ and designers’ experiments with commons, Open Source culture, post-humanism and biopolitics, alternative economies, and community organization. Artists do not simply depict or reflect upon these varying perspectives from a critical distance, but radically translate them into their everyday ways of living and working, in other words, into material practices. This book aims to explicate tacit knowledge from artists’ material practices and from real-life experiments conducted in a world in crisis while gaining insight into present-day paradigm shifts in the arts.

The different disciplinary groundings of our contributors correspond to the respective disciplinary groundings and research specializations within the material practices workgroup: Leiden University, Willem de Kooning Academy, Het Nieuwe Instituut, Waag, West Den Haag. Based on the expertise and the discussions in the workgroup, contributors were invited who could help to both focus and complicate the question of how artists practices and real-life experiments amount to knowledge for ways of living and survival in the planetary crisis.

reading guide

The vocabulary of concepts relating to collective material art practices presented here is not an encyclopaedia nor even an inventory and it is by no means complete. It may be regarded as a thought experiment, aimed at stimulating further debate and new vocabularies.

The entries are categorized under seven headings, laid out in alphabetical order: bodies, collective, critique, economy, making, matter, and undisciplined. In some cases, entries refer to connected entries.

The order of reading is not linear. You are invited to read the entries in any given order.

bodies

embeddedness

In assembling ideas that are seemingly disconnected and uneven (the seabird and the epilogue, the song and the soil, the punch clock and the ecosystem, the streetlight

and the kick-on-beat), the logic

of knowing-to-prove is unsustainable because incongruity appears to be

offering atypical thinking.

Yet curiosity thrives.[5]

embeddedness:

to be set solidly into a mass

Ship merchants operating from the Liverpool docks in the nineteenth century needed the tides predicted and their clocks calibrated, so they commissioned the Bidston Observatory. The observatory was to be strategically situated on the highest point of the Wirral peninsula, overlooking the river Mersey, the river Dee, and the Irish sea. Completed in 1866, it was made out of sandstone extracted from the bedrock below, creating a cavity which now forms the observatories’ extensive basements.[6] Around the building, a deep moat was dug to minimize interference from neighbouring traffic. The plinth in the picture (p. 30) is a ‘bedrock connection point’, located in the observatory sub-vault. Sheltered from temperature shifts and movements from elsewhere, the plinth provided a stable platform for a century of exacting earth observation.

Cornwall, last fall. Suddenly they feel the ground tremble, and hear windows rattle. Afterwards, Dr. Ryan Law, managing director of Geothermal Engineering explains to the local press:

As part of the United Downs Deep Geothermal Power testing, we did cause some micro-seismicity. Although this was within our regulatory limits,

we are stopping operations until we understand the cause. The tremors are low-scale and should not be anything to be afraid of.[7]

Geothermal energy is produced by harnessing heat from the earth’s core. To produce power from this heat, extremely deep wells need to be drilled and water is pumped through them at high pressure. Since the Bronze age, Cornwall has been mined for tin, copper, arsenic, and lithium. Tremors in the porous underground are set off as a result of the additional disturbance caused by geothermal boring. In the non-committal words of the general manager, they sense all the troubles that wreck the earth: ‘we caused micro-seismicity’ ... ‘within our regulatory limits’ ... ‘until we understand the cause’ ... ‘not anything to be afraid of’.

embeddedness:

laying in a bed of surrounding matter

South or north of here, already more than ten years ago. It takes him many long days to level the driveway of his holiday home. Using a barre à mine, a forged iron bar originally used by miners to pound the ground and break the surface, his movements reverberate through the valley. Eventually, he hits an immovable piece of rock and the pounding stops. He points, almost proudly, and says: ‘look, the earth!’

Early on, the observatory installed a seismometer on the sub-vault plinth. Kept in the dark, it continuously auto-registered slight movements on light sensitive paper that corresponded with earthquakes experienced on the other side of the planet. A Milne-Shaw Vertical Tiltmeter was acquired in 1910, a precision instrument based on the same principle as the seismograph, where one part remains stationary and fixed, while another part moves together with the earth’s surface. The vertical tiltmeter derives its precision from using a rigid arm that points upwards, with a pendulum hanging down from it. The swinging of the pendulum, with its fulcrum fixed to the bedrock connection point, makes micro-seismicity observable by magnifying the actual motion of the earth. It was with this instrument that the phenomena of ‘tidal load’ could be observed, the oscillating north-south tilt of the Wirral peninsula due to the strain of the water weighing down the bedrock (and subsequently, the plinth itself) at high tide.

A physiotherapist once told me about her interest in how bodies feel their way around with the help of instruments. She explained her fascination through the example of cooking a soup or a sauce. If you stir the bottom with a wooden spoon, she said, you will feel precisely at which moment it starts to catch. You do not need to put your hand into the hot liquid to touch the bottom of the pan.

At the observatory, the so-called ‘ocean loading effect’ continued to be registered with increased precision until the early seventies, when the expanding data about earth tides from around the world started to show unexplained discrepancies in neighbouring sites; the magnitude of the north-south tilt varied by twenty percent when measured in one end of its sub-vault, or the other. In an article called ‘Tidal Tilt Anomalies’, two scientists working at Bidston claimed that these inconsistencies could be explained by unknowable couplings between the landmass movement and the strain on the site itself. ‘A mine or a tunnel, in which tilt measurements are usually taken, represents a discontinuity in the Earth’s crust.’[8] By comparing different types of instruments, they found that tiltmeters were extremely accurate but that they were measuring tidal tilt in combination with hyper local movements due to situated geological conditions. Tidal tilt observations where eventually abandoned due to non-compliant embedded data.

embeddedness:

trembling with the earth

As with many material evidences of techno-scientific progress, the appointing of stability, the fixing of a point zero wherever convenient, seems to require an entitled mode of being in the world.

Each point is merely a conceptual marker, which can be assigned and reassigned in the equation hierarchy as the ‘coordinating zero point’ and every line can be formed to be the ‘coordinating axis’.[9]

Power arranges itself around such arbitrary vantage points, through which the movement of goods and people elsewhere can be controlled. Contributing to the reliable navigation of ships across the British empire, but also actively and continuously supporting the convenient fable of transparent observation, the Bidston Observatory aligned with different scales of capitalist endeavour, exploitation, colonialist and imperialist modes of worlding.[10]

He is being driven around his native island Martinique, pointing out the places that he grew up in and that vanished after the earthquakes. The island is part of an archipelago located on the crumbling intersection of two tectonic plates, which makes the geo-plasticity of the earth regularly interact with human activity. ‘We understand the world better if we tremble with it’, he explains.[11]

To be embedded depends politically nor epistemologically on a fixed locus of observation. It opposes systematic thinking without fear, because it is a mode of understanding the world that resonates with the multidimensional and multidirectional impact of being embedded, of its inherent instability. Embeddedness is to ‘tremble with the world’.

The image cuts back to the view from the car window, an undulating green landscape moving by under a bright blue sky filled with clouds. He continues:

The world trembles in every way. It trembles organically and geologically. It trembles even with the climate, poor me, as far

as I know. But the world also trembles through the relations

we have with each other.[12]

- ↑ The term ‘art’ is used here in its broadest sense, encompassing visual art, design, performance art, new media practices and other artistic disciplines.

- ↑ Peter Osborne, Anywhere of Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art (London and New York: Verso, 2013), p. 48.

- ↑ For the 2021 Turner Prize only artist collectives were nominated: Array Collective, Black Obsidian Sound System, Cooking Sections, Gentle/Radical and Project Art Works.

- ↑ This contribution is based on the script for a performative introduction to the sub-vault of the Bidston Observatory Artistic Research Centre (BOARC) for participants of the work session Down Dwars Delà, organized by Constant and BOARC, Liverpool, August 2021, constantvzw.org/site/Open-call-study-session-Down-Dwars-Dela-2-UK.

- ↑ Katherine McKitttrick, Dear Science and Other Stories (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), p. 4.

- ↑ The Bidston Observatory was built on the solid bedrock of the Wirral peninsula, ‘a capping of Keuper sandstone on soft Upper Bunter’, which was considered to be more stable than other geological arrangements elsewhere. Joyce Scoffield, Bidston Observatory: The Place and the People (Merseyside: Countyvise Ltd, 2006).

- ↑ Sabi Phagura, ‘Houses shake as Cornwall is rocked by FIFTEEN “earthquakes” measuring up to 1.5 in magnitude in two days caused by tests at geothermal drilling site’, Daily Mail, 1 October 2020, dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8794885/Houses-shake-Cornwall-rocked-15-earthquakes-two-days.html.

- ↑ T.F. Baker and G.W. Lennon, ‘Tidal Tilt Anomalies’, Nature 243 (1973), pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Clancy Wilmott, Mobile Mapping Space: Cartography and the Digital (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020).

- ↑ ‘The Center is Open/HECS is ajar!’, wiki.bidstonobservatory.org/index.php/About.

- ↑ Manthia Diawara, ‘One World in Relation: Édouard Glissant in Conversation with Manthia Diawara’, NKA Journal of Contemporary African Art 28 (Spring 2011), pp. 4–19.

- ↑ Ibid.

gestures

But what would those technical images look like? How might they come to be employed for the critical purpose proposed by Flusser? Luckily, he was able to demonstrate what he had in mind, in a series of collaborations with artists. In experimental videos that he made with the sociological artist Fred Forest, Flusser explored the power of the human gesture as one of the new possibilities for critical human thinking, unlocked through video technology. In the video, Flusser can be seen gesturing avidly as he speaks about gesture. Forest, too, is instructed to gesture with his camera movements, and to criticize Flusser through these gestures. Likewise, Flusser instructs the future viewers of the video to use their own gestures in order to criticize both him and Forest. The viewers’ gestural feedback should then, Flusser and Forest intended, be captured on video, too, and edited into the next iteration of the tape.

This playful exercise is not only a new form of philosophy for the age of technical images. It also points to a more general critique of cultural production. The semantic content of an utterance fades behind the gesture with which the utterance is made. Additionally, this thinking through gestures is patently embodied and situated: It breaks with the enlightenment and modern-age pretension of an abstract, disembodied, pure rationality, embraces contingency, subjective experience, and becomes open for more people. Flusser’s commitment was in tune with his times and various critical revisions of enlightenment rationality in the twentieth century.

It was an answer to the challenge of how to reject disembodied rationalism without also giving up the possibility of critical thinking. This issue had also been explored by his contemporaries Marshall McLuhan

—with his penchant for slang and vernacular—

and Donna Haraway with her leaky neologisms and troubled ironies.

In the gesture, the intent of the utterance and the effects it produces, the experience it generates, is more important than any particular semantic content. In other words, non-verbal communication is more important than verbal communication, connotation more important than denotation. Consider the Facebook algorithm, which allows advertisers to manipulate the emotions of target demographics in real time, as revealed in the 2017 Cambridge Analytica scandal. Advertisers no longer send merely one message lauding their product. Instead, they send a series of messages, which in their aggregation nudge their human targets towards the desired purchases or other behaviour. In the electronic age, the gesture of publishing is thus fragmented into myriad probing moments. As McLuhan quipped, the medium is the massage.

A show in the cybernetic community Alphabetum, ‘Free Emojis’, explored emojis as a contemporary manifestation of gestural communication. What Flusser had provoked his readers with in the 1980s, has become today’s reality. Digital natives are indeed finding that technical images are far more apt for the analysis, commentary, and communication of our experience in the electronic age. Conversely, by observing emoji use we discover that text has not disappeared. In fact, we are writing and reading more than ever before while text has become more explicitly gestural.

hosting

During the Making Matters conference (November 2020), three live Etherpad sessions were hosted by researchers Anja Groten, Eleni Kamma and Pia Louwerens. These were interactive meetings in an online collaborative notepad, where participants discussed symposium topics that came up during the conference. Each of the three sessions experimented with online collaborative engagement. Communicating through the pad takes place purely on a level of ideas and writing and utilizes one’s ability to relate mentally through typing. All participants control and co-edit the text that is produced on the pad during the meeting. Despite its democratic intentions, the pad privileges those who prefer writing over speaking as a means of expression; it does not allow for equal access or experience for analphabets, people who have dyslexia and other learning disorders; and it excludes active participation for those not explicitly invited to the conversation. The one(s) who set up a conversation on the pad are also those who establish the group and do the inviting by sending the link. It depends on the pad’s host(s) whether they will publicly or privately share the link online.

On March 3, 2021, I explored ‘hosting’ further through an online participatory event hosted by Jubilee, a platform for artistic research and production, of which I am a member. The aim of this experimental public event, which consisted of four unique presentations, was to offer perspectives on nourishing through online communication tools. Upon registration, future participants were sent four simple ‘recipes’ (each conceived by one of the event’s hosts: Samah Hijawi, Philippine Hoegen, Eleni Kamma and Gosie Vervloessem), which they were invited to prepare beforehand. This event was recorded.

My prepared script went as follows:

1. Welcoming the audience

(we see and hear each other on Zoom)

Welcome! Tonight, we will explore a pilot version of ‘The Corners of the Mouth’, a project I initiated that focuses on our current hybrid life of physical confinement and increased online presence. How can we use this hybridity to cultivate new forms of artistic expression and strengthen the relation between ‘I’ and ‘we’ (‘we’ meaning: virtual communities of contemporary online users)? Tonight, I, Eleni Kamma, have invited Brussels-based artists Samah Hijawi, Gosie Vervloessem and Philippine Hoegen to share their expertise in practicing affective communication. Over the following two hours, we will offer different perspectives on recipes and nourishment. First, I will take around 20–25 minutes and ask you to take your drink and join us on Etherpad. Please stop your videos but do not mute yourselves. The link is in the chat. Please follow it and meet me there.

2. Participants come to the pad

(we hear each other on Zoom)

Please position your cursor in the space of the pad and experiment with typing. Could you share your name and what you are currently drinking with us?

I would encourage you to actively sense how your favourite beverage slowly slides from your mouth into your digestive system during the following twenty minutes.

During the first lockdown I became interested in whether Etherpad, an open-source online text editor, can reflect collectivity in these times. On Etherpad, each user’s contributions are indicated by a colour code and recorded onscreen in real time. Thought processes are revealed as thinking takes shape through typing. The pad enables writing that is collectively performed and witnessed.

I type:

Since then (especially during lockdowns), I think about communication under hybrid conditions, more precisely about possibilities to create affect by combining physical and digital communication processes.

I type:

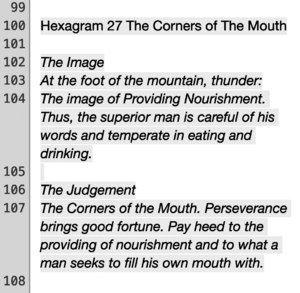

Faced with this question, I consulted the I Ching or The Book of Changes, an ancient Chinese form of divination consisting of 64 hexagrams. With a question in mind, you drop the coin six times, receiving a hexagram. The answer to my question was:

Several readings by commentators are available, such as Richard Wilhelm’s:

I am puzzled about how to interpret this.

What abstract images can ‘we’ construct with the question, the people involved, the time and place we are in? I will now feed the pad with the Hexagram’s lines that led me here. I invite you to a collaborative reading of the text. Let’s eat and digest the Hexagram’s words together. I invite you to vocalize the text, any way you like, loud, soft, or in your own language. Please try to both respect your rhythm and listen to the others!

- Line 1 (bottom line): You let your magic tortoise go, and look at me with the corners of your mouth drooping. Misfortune.

- Line 2: Turning to the summit for nourishment, deviating from the path to seek nourishment from the hill. Continuing to do this brings misfortune.

- Line 3: Turning away from nourishment. Perseverance brings misfortune. Do not act thus for ten years. Nothing serves to further.

- Line 4: Turning to the summit for provision of nourishment brings good fortune. Spying about with sharp eyes like a tiger with insatiable craving. No blame.

- Line 5: Turning away from the path. To remain persevering brings good fortune. One should not cross the great water.

- Line 6 (top line): The source of nourishment. Awareness of danger brings good fortune. It furthers one to cross the great water.

While I am typing this, we hear an ensemble of voices reading/translating the text in several languages. Simultaneously, the user icons indicate who speaks

on Zoom.

Thank you! Let’s take five minutes together on the pad. Consider it a digestion-absorption process. Feel free to select a spot on the pad, to find your position along the text. You are welcome to re-feed the pad and the rest of us with your thoughts, feelings, experiences, and concerns in relation to ‘The Corners of the Mouth’.

Audio playing: (belly noises) Water enters the hungry belly

collective

collective organization

logistics part II

EWH: I think the need to play with formats of work, organization, and distribution are now more urgent than ever before—not because crisis is upon us, but because the problems that were always there have been revealed more blatantly. Why art, design, and culture are still important is because they deal with methodologies—comings together and ways of seeing and playing that precede the politics that most everyday folk don’t even realize addresses (or neglects, or unfairly treats) them. So education, and welfare, and government funding all need to go through a self-reflexive hall of mirrors, so to speak.

FC: I couldn’t agree more. At the same time, I’m afraid of the empty gestures and buzzwords that will get ticked off (like, for example, ‘care’ as a now-ubiquitous noun in art project funding application prose) if this becomes more mainstream. In Europe, I also witness the constant failure of artists to truly commit to collective projects and not just use them as platforms for displaying/performing their individual portfolios.

EWH: Yes, it is not surprising at all that we’ve watched the hype on care build up over the last year, but as someone primarily confined to margins, the mainstreaming of discourses is also something to learn and navigate as part of our practices. The tricky thing about care, and so many other widely debated issues is that they really need to be enacted rather than simply theorized or talked about. But the need to repeat, repeat, and repeat again to people who are less affected by what is lacking in the socioeconomic system (power is a crux issue at every scale) is a necessary part of expanding possibility. It entails ‘mainstreaming’ and popularizing and this gives those of us who do want to speak and practice from a position without power a tremendous pressure to

re-circuit, re-articulate, and re-work the existing imaginaries.

What you mentioned about the failure to really collectivize in Europe is also a problem in Hong Kong and China. When HomeShop, the artist-run project space I was involved with from 2008–2013, was invited to participate in the ‘Unlived by What is Seen’ exhibition in 2014, the curators told us they wanted to include us as a collective practice because they felt that all the other collectives they observed in China at the time were merely solidarity-for-opportunity kinds of conglomerations, often splitting up when the group becomes famous enough that the individuals of a group can then make their way with solo careers.

So it’s no wonder that so many of us have that starry-eyed fascination with the hype of many Indonesian collectives, haha, but as discussed with my friend Riar Rizaldi in a talk a couple of weeks ago, there are many problems there as well that tend not to get discussed publicly, and the exportation of nongkrong can in some ways be just as much of a selling strategy like anything else.

That said, having much more time to read and dilly-dally around in a confined space these days, I finally got to read your paper on 1970s Mail Art more carefully, and the key value I can take from the various examples you present is to see similar struggles and resonances resulting in similar impulses and tactics, such that your idea of the ‘eternal network’ represents a notion of affinity.

FC: Yes, and I am also wondering whether these struggles, resonances, and mistakes need to be constantly re-enacted and repeated by each new

EWH: There are changes along the way, from generation-to-generation mutation. But I fear that despite such continuities, there is also a repetitive relegation to the realm of marginal play. Whatever foresight those projects from the sixties forward had for internet behaviours today—and as you say our pinpointing of AI/algorithms as the evils of the system is misplaced—how could intimate and networked actions parasitizing off of larger infrastructures really affect anything?

FC: Maybe that’s the problem—that, by focusing on (larger societal) effects, we’re unintentionally superimposing growth or impact expectations on these projects while their main value might have been their subjective-collective experience, and functioning as an experiment?

EWH: Thank you for the reminder. I have to tell myself again and again in so many arenas to focus upon ‘subjective-collective experience, and functioning as an experiment’, rather than the unintentional but hard-to-escape notions of growth, development, and impact, as you say… The question of change is perhaps naïve and misplaced. Regardless, it is difficult not to acknowledge outcomes as part of the process of communication that happens among any form of collective organizing. How that communication occurs is central to the difference between centralized or decentralized processes, and I think Display Distribute’s inquiry into grey economies actually implicates us within certain murky areas between centralization and decentralization. These have been some of the greatest challenges to the project, but they are reasons to continue. You are right that ‘radical inclusivity’ does not necessarily garner any momentum, but neither do elitism and the reverse snobbery of oligarchic movements, which is a critique of both ends of the political spectrum.

If as you say the main value is located in the experiment of a subjective-collective experience, then your previous question might be answered by saying that the constant re-enactments and repetitions by new generations are necessary. Embodiment and affect cannot be historically reviewed except as practiced singularities, right?

FC: Yes, but you could also criticize that as a petty-bourgeois hobbyist self-limitation that gives up on the larger picture…

EWH: Completely on the mark as well! There is a close friend with whom I have had many emotional disputes along these lines, and perhaps this pinpointed critique precisely circles us back in some way—whether as a picture or a way of manoeuvring—to the necessities of an eternal network.

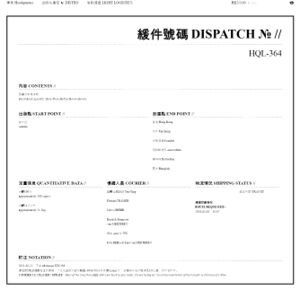

2021-02-19

Dear 慢遞員易拎何子 (& 妍廷),

HQL-364 is currently quarantined in a hotel in Taichung. Elaine, I hope it’s not a major let-down that we have only been able to bag thirteen copies because of the bulkiness of Yenting’s luggage. My agreement with courier Amy S. Wu was that she would give me a large stack of copies and that I would return to her whatever wouldn’t fit the luggage. The remaining 62 copies are currently at my home and still need to be returned to Amy, who lives nearby.

Florian

cybernetic community

Our actions have effects and these effects act back upon us in a learning process. While this is an uncontroversial statement, the age of hyper automation gives us the impression that this experience is massively compounded, as in a meta-butterfly effect, a feedforward hall of mirrors, or hell of mirrors. Our actions seem to have at once too little and too much consequence. How to get the right sense of scale in today’s intensively networked environment? Community no longer seems to have continuity, but appears to be an ad hoc grouping which could just as well be otherwise. One can be a part of several ‘communities’ at once, and then just as suddenly, of several others. As a community, we act as intersections of multi-dimensional Venn diagrams where our world of associations reconfigures around us in real time.

Of course community still has a centre of gravity, its provisional situatedness. In tension with the networked context, every member of a community has its own situatedness, if only in that of their physical body or device. What happens if a social network is radically distributed, and no longer runs on a central server, as in the case of software projects like Patchwork/SecureScuttlebutt? Then the network coheres around the chief maintainers of the project.

A community is always intractably material. What we would like to examine are the relationships and tensions between the participants and the material apparatus that entertains them. The physical space of the contemporary art institute West Den Haag includes an ‘Alphabetum’ which could be called a proto-institutionality dedicated to the forms of letters (grammatography). The community around the Alphabetum coalesces around its physical space, just as a community of an online social network coalesces in its respective physical space, i.e., its servers.

The Alphabetum functions as a laboratory for cybernetic community knowledge creation, the generation of unlikely and unexpected forms of expression and exchange. Also, as it is cybernetic, it is committed to storage, archiving as a recursive practice in a kind of communal learning. The exhibitions in the Alphabetum are probes sent out into the community for responses, which are processed and built into subsequent exhibitions. Through this recursive feedback process, the Alphabetum ‘learns’ about the environment that is interested in the programme. At the same time, it is instrumented by the public to respond to their interests. This community exercise is concretized in the exhibits on display in the Alphabetum, which are subsequently curated and recontextualized by the community.

platform

a platform design request

In recent years the Hackers & Designers collective[1]

has been frequently approached by organizations and initiatives from the fields of art, design, technology, and academia with the question: ‘Do you want to design our platform?’ An intricate question as the term platform refers to a multitude of phenomena and objects. The platform’s ambiguity seems particularly amplified when articulated as part of a design brief, suggesting that the platform is to be an expansion of the realm of designed things.

An organization as platform supports individuals or groups in addressing an audience. In a computational context, the term platform refers to a technical infrastructure, for instance an environment in which software applications are designed, deployed, or used, such as computer hardware, operating systems, gaming devices, mobile devices.[2]

With the H&D collective we have designed, built, and maintained technical infrastructures, such as software, webware, and services that enable online collaboration, production, organization, and publishing of digital content. Such diy platforms are tool convergences that—in their particular composition—cater to the particular needs of the collective. They are content management systems,[3] chat applications,[4] collaborative writing tools,[5] online spreadsheets[6] and file sharing systems.[7] These self-made, appropriated or hacked tools and systems are implicated in the ways the members of the collective work together. H&D’s technical infrastructure continuously evolves, and at times fails, or acts in an unexpected way. H&D shapes and reshapes its modes of organizing around the possibilities and limitations of such self-made platforms—along with learning to cope with system incompatibilities, broken links, expired protocols, and unreliable backups. Therefore, the notion of platform is at the core of its existence.

The platform-design request implies that a platform can be regarded as separate from its context, and that there is a causal relationship between platform and design. However, because of how the H&D collective has developed relationships with technical infrastructures

it would be difficult to disconnect the technical aspects from the organizational and social aspects of platforms. The question then arises whether platforms—in the way

we relate to them at H&D, as an inherent part of the collective’s fabric, including its characteristic of constant emergence, spontaneity, and unreliability—

can be designed at all?

In my view, the question: ‘Do you want to design

our platform?’ wrongly implies a certain fixedness,

a beginning and an end of a digital platform

and the possibility to foresee a platform’s trajectory.

The ‘commissioners’ who formulated the request position themselves as end users of the platform, and suggest some kind of ownership of it. It would be ‘their’ platform that ‘we’ are designing. However, a platform, as I see it, in its manifold of meanings is interwoven in collective practice and cannot be owned.

thinking with platforms

Besides its technical connotations, the term platform is also often used figuratively, for instance referring to organizations such as H&D. As such, it tends to assign an assumed value to the platform-organization as supportive and enabling, and risks a flattening of the technical and organizational particularities and implications of a collective. The question is how to think with the various meanings of ‘platform’? How do platform’s different (technical, organizational, architectural, political) connotations intersect—act together and apart?

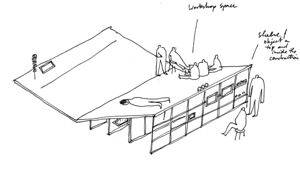

In 2020, H&D developed a physical structure,[8] the ‘H&D platform’, together with architectural designer Thomas Rustemeyer. The installation was meant to represent the H&D collective in its endeavour to bring together different practitioners, artists, designers, and computer programmers[9] and facilitate exchanges among them. The platform would be activated at different moments, for instance as a workshop space, a stage for performances and presentations, and as a reading room.

However, due to the global Covid-19 pandemic the platform as we had initially envisioned it remained more or less unvisited and untouched. Yet, through the sudden need for our planned activities to continue online, we developed other, digital, means of pursuing our activities. For instance, we created a project website that showcases the work of the contributing artists[10] and draws together their research and process documentation. We furthermore developed the ‘H&D livestream platform’ as we witnessed an increasing fatigue of commercial platforms. The fatigue is caused by large tech companies such as Google, Facebook, Microsoft or Zoom, who profit from their user’s reliance upon them in times of crisis by selling their data.[11]

The H&D livestream platform converges an open-source streaming software, a streaming service, and a chat interface.[12] Certainly less clumsy ‘off-the-shelf’ platforms do exist. The H&D livestream platform ‘acted up’ and caused moments of discomfort through its glitches and lags. However, it sustained its appearance, and has hosted many online H&D events in different contexts.

In the context of H&D, the collective seems to establish intrinsic relationships with digital tools and technical infrastructures that expand the realm of utility. An important part of building and maintaining such relationships are the manners in which the collective copes with unreliability, exercising patience and curiosity towards unintended technical glitches. In such a context, platforms can therefore not be described as self-contained entities. They travel between a multiplicity of meanings and inhabit collective peculiarities, as they are designed and redesigned in action and through interaction, which, in my view, makes it impossible to uphold a user-designer distinction.

To recap, a self-organized collective such as H&D shapes itself through technical infrastructures. In turn, technical infrastructures also continuously evolve with the collective, oftentimes in unpredictable ways. The emerging technical infrastructure around the aforementioned exhibition project is an example of that. Through their co-evolvement with collective practice, such platforms can therefore not be described as disconnected from collectivity.

public time

The term public time is relevant for the notion of parrhesia—meaning the courage to speak one’s mind—and for parrhesiastic practices, which I approach as exercises, understood in the ancient Greek context of askesis or disciplined practice. These exercises aim at finding the courage to speak one’s mind by positioning and expressing oneself in relation to others. This happens through an expanded version of performativity that focuses on the right of the people (non-privileged as much as privileged) to ‘appear’ and on the potential of technology and virtual participation to enable the appearance of these bodies. In the field of art, parrhesiastic practices often reveal uncomfortable truths about conventions by undoing dignity and seriousness. They aim at engaging and affecting the spectator through various strategies, ranging from playful, friendly, and healing, to confrontational, disruptive, or aggressive. Unlike trolling phenomena taking place in online social communities, for the one who practices parrhesia this revealing of uncomfortable truths needs to be coupled with some kind of implication, engagement, self-exposure, and a sense of personal responsibility and shame. At that very moment in which the parrhesiast speaks boldly, not only does he/she tackle truth and existing power relations, but also his/her own subjectivity. In finding the courage to examine one’s self and by putting his/her beliefs to the test on a daily basis, the one

who practices parrhesia is freed from previous experiences, prejudices, and forms of control imposed on him/her through the ‘common opinion’. In this sense the parrhesiast is constantly subjected to self-transformation and/or self-de/reconstruction.

In Philosophy, Politics, Autonomy: Essays in Political Philosophy (1991), Greek-French philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis defines public time in a historiographic sense and discusses parrhesia in relation to the ‘project of autonomy.’ Two roots exist within the Greek word autonomy: autos (εγώ ο ίδιος = myself) and nomos (law). An autonomous person creates his/her own law. Castoriadis argues that the first political society in which the citizens took the responsibility for their way of living and for legislatory regulations of social relations was in Ancient Greece. He posits that the possibility to ask questions as an individual or a group regarding social institutions occurred for the first time in Athens in the fifth century BCE. In this tradition, citizens contribute to the creation of public space (and public time) through the co-existence of three necessary and decisive phenomena: courage (parrhesia), responsibility (euthini), and shame (aidos, aischune).

In my presentation at the Making Matters Symposium (November 2020), I considered Etherpad as a tool for co-creating public time. Between February 16 and March 21, 2021, Thalia Hoffman (TH) and myself (EK) further discussed the term.

Public

Who is the public? ‘Public’ here is an adjective defining the type of time. But indeed, who is the public in the case of a public artistic event? Is this type of open participation enough to create a shared sense of collectivity among the participants? What does a shared sense of collectivity contain? I suggest each participant needs to see/feel their contribution to the collective… which can be at the same time seen/felt/inspected by the collective body of participants, enhancing in this way an understanding of individual contribution as responsibility.

Time

The Etherpad is an open-source online text editor. Each user’s contributions are indicated by a colour code and are recorded onscreen in real time. Unlike discussions in a physical gathering (where unspoken communication expressed through facial expressions and bodily gestures accompanies words) or cloud-based platforms for video conferencing (where participants stare at each other’s faces, talking heads videos arranged next to each other) communicating through the pad takes place purely on the level of ideas and the ability to relate mentally. Do only words communicate ideas? Words communicate ideas on the pad, but also something about the thinking process, the doubts and the hesitations involved in it: the movement of the interactions between our words, the time gaps, the mistakes, the erasures and re-writings. So maybe the pad (public space) needs to collect these gaps, doubts, and hesitations, and not erase them? It is not the pad that collects the gaps, doubts, and hesitations, but all participants together that make use of it to create this collection. But this is also what makes the pad a vulnerable tool for collecting content; any participant can erase the content with one click. Everyone can see what is written at the same time. The thought process is revealed, how thinking takes shape through typing. Does the typing change the thinking as well? Yes, the typing may change the thinking, provided one enters the pad in a state of mind open to change/dialogue, not set on a prefixed message one wishes to convey. I agree, being open for dialogue is needed many times for the possibility of change. I wondered though if the actual physical act of typing also changes the course of thinking. If we had a conversation with spoken words instead, would this change our thinking about concepts and ideas? I am not sure it would change our thinking about concepts, but there is this mechanical, repetitive aspect within the typing process that might interfere with one’s course of thinking. It provokes people to react to each other on the spot. You type something and it is immediately there. Can this be described as performative writing? Yes! I feel we need to capture the ‘liveness’ of this performance. Something that reveals its becoming. Maybe recorded typing? Or performative co-typing that has the potential to be recorded? You can go back and erase it, but people can see this as everything is documented immediately. Online/digital media make it difficult to read each other, as the senses are limited to sight and hearing. Through this visualization of thought, it is feasible to collectively write and speak, to influence our thinking, to both witness and testify. I am interested in considering the pad as a tool for creating public time. Can it grasp collectivity in these times? Does collectivity need public time? or vice versa? Maybe they are interdependent? Collectivity needs public time to reflect on and inspect its own past actions, but also public time cannot exist without a collectivity. What do you think? I think there is an element of time that is always shared. What makes it public in the sense we are trying to capture here, is that the ‘public’ is doing something additional together during this time, something that is more than spending time together. Maybe we should ask what needs to happen in time to make it collective? I agree. Maybe it has to do with future decisions, actions, experiences that will have an effect on people, both individually and collectively.

Are we trying to create public space here? Since we are working on the same text but at separate times?

I think what we are trying to do here is creating both public space and public time. This is how I became interested in Castoriadis, because he brings public time in the conversation as going hand-in-hand with the creation of public space. He finds these two indispensable for what he calls ‘the project of autonomy’* of Ancient Greek democracy. I connect this with my suggestion to connect the personal to the shared, and through that define the collectiveness of this time.

Can time be private? Yes. When I am daydreaming, reading a book, or drawing, I withdraw to a personal sense of time, and I don’t feel the need to share this with others. But this happens within a ‘bigger’ time that is public and local. The personal sense of time is always part of the time of the day at the particular place where it occurs, meaning it is public and local. I also feel time is always private as much as it is public, even if I share time with others, there is always the way I sense the time we spend together. If ‘public’ goes hand in hand with being exposed/accessible to everyone, are obscure and concealed activities also part of public time?

zoöp

The sound of the desperate voices of collectives of animals, plants, and other bodies alive today can be harsh to the senses, and it demands an effort and dedication to take those voices into account.[15] The Zoöp way of working aims to concretize this effort. It has three goals: firstly, to strengthen the political and legal standing of other-than-human life within human capitalist societies. Secondly, to support ecological regeneration, in Zoöp vocabulary: Zoöps want to develop the zoönomy (a regenerative economy that secures the quality of life of multispecies collectivities) within and surrounding Zoöps. Thirdly, the aim of the initiators is to make the Zoöp model widely adoptable and put into practice by a variety of organizations, from farms to municipalities, from hotels to cemeteries, from commercial enterprises to non-profit organizations. The Zoöp model is the centrepiece of the Zoöp movement and shapes anchoring bodies for the larger practice of zoönomy.

In order to facilitate the development of the Zoöp movement, two legal bodies have been founded in 2022. One is the Zoönomic Institute. Its task is to help organizations to transform themselves into Zoöps. It grants organizations the right to call themselves Zoöps. The other one is the Zoönomic Foundation. As laid down in its statutes, the Zoönomic Foundation has one task only: to articulate and represent the needs and interests of other-than-human life in the spatial and operational domain of Zoöps and to translate these into organizational decision making.

Organizations that turn into a Zoöp keep their existing function—a school remains a school, a farm remains a farm, a hotel a hotel—but set themselves an additional goal, which is to foster zoönomy. An organization can be be accredited as Zoöp[16] by doing two things: first it grants the Zoönomic Foundation an observer seat on its board (or whatever body in charge of its policies). This seat is then filled by a human Speaker for the Living. The Speaker for the Living is bound to the statutes of the Zoönomic Foundation and acts as the speculative and political organ for other-than-human life in the Zoöp. Secondly, the organization commits itself to follow the Zoönomic annual cycle, by which it gradually transforms its operation, intervention

The development of the Zoöp concept was inspired by the now famous Rights of Nature cases of Whanganui river, Mount Taranaki, and Te Urewera forest. These three collective other-than-human bodies are the living ancestors of different New Zealand Iwi, tribes of the Maori, New Zealand’s indigenous people. The river, mountain, and forest were granted legal personhood in the New Zealand jurisdiction between 2014 and 2017. In legal terms, they became incorporated other-than-humans. Whenever necessary, they are represented by human members of their respective Iwi.

In Western cultural tradition, collective bodies of other-than-humans do not have the status of ancestors. In fact, they are not even considered subjects, but resources, which caused the ecological disaster we find ourselves in. Although there is a growing movement of Rights of Nature legal and other activists, the legislative reform by which living other-than-humans should gain rights will be slow and thorny.

The Zoöp organizational format does not require the legislative reform that rights of nature require, but uses existing instruments of private law. Zoöp does not grant rights or personhood to living other-than-human entities but operates on the premise of them already having rights. Zoöp is intended as a way of organizing, a practice, a procedure that actively acknowledges these rights and the subjective experience of other-than-human life. It is focused on collaboration between human and other-than-human life. In this sense, the Zoöp model is a pragmatic shortcut to a Rights of Nature

With the governance structure and the Zoönomic Foundation in place, a Zoöp, commits itself to figuring out how its operation can transform itself into a regenerative practice, contributing to the quality of life of a human inclusive ecology. It does so by following the Zoönomic annual cycle of four movements, called Demarcating, Observing & Sensing, Characterizing and Intervening.[18]

Demarcating answers the question: which (legal, human, organizational, and other-than-human) bodies form the Zoöp?[19] Demarcating situates the Zoöp’s practice in its environment and articulates its locally specific questions for actual ‘collective bodies’.

Observing & Sensing is concerned with understanding the life-worlds of the different bodies that make up a Zoöp, and with the question of whether and how those bodies perceive and acknowledge each other’s Zoöp participation.

Characterizing involves asking the question how the different bodies enhance or obstruct each other’s quality of life. This will result in a first kind-of-diagnosis of the Zoöp’s ecological integrity and exploration of interventions.

Intervening, then, is the process of actually changing the spatial arrangements, organizational practice or relational fabric of a Zoöp. Its primary objective is a local, thriving, combined human and other-than-human community that provides groundwork for other, more global aspects of the transformation of economy into zoönomy.

At the time of writing, more than twenty organizations (farms, cultural institutions, holiday parks, educational institutions and others) have committed themselves to becoming a Zoöp. On 22 April 2022, Earth Day, Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam has become the first actual Zoöp in the world.

critique

criticality

The school was demolished and was offered a ‘new’ space in an old and decrepit building, classified as a ‘monument’ or listed building, opposite the original location. The renovation would partly be paid for by the real estate developer of the Klundertoren. After a disastrous process of moving the school into a building of which the renovation was not finished, the responsible councillor decided two years later that the school would have to move again, to make way for another X-tower. At this point, a group of parents said ‘no’. Without knowing it at the time, they opposed a development project that involved an estimated investment of around 50 million euros. In a sense,

they were critically unaware.

1. experiencing criticality

Battles like these take a lot of time. One question is how long people are prepared to keep on fighting and stick together. For a real estate developer, five years, or ten years, or even fifteen years is nothing. On the contrary, years may add to profit. Let’s call this the critical limit of perseverance. In this case, the battle would take five years.

Real estate developers may, on the face of it, function within the limits of the law, but are often closely allied with parties that do not. First, there were two clumsy, nightly attempts to set the listed building containing the school on fire. Then, during a gymnastics class of six- and seven-year-olds in the gym on the first floor, the stairway leading up to the gym was set on fire, as well as the doors to the emergency exit. An astute teacher grabbed a bench, pushed it through the window and helped the children escape via the roof of the neighbouring building. Let us call this the criticality of the situation.

In a civil society, this is serious business. Now that their children had been brought into a life-threatening situation by an unknown actor, the parents might have decided to give up. Yet the burned shoes of the children that had been left before the door of the gym inspired them to contact the mayor, who in the Dutch system is in charge of the police. When the responsible councillor told the city council what had happened, there was a strange, chilling silence that had its political effect. The school was granted the permission to stay, and the building would be properly renovated. A fourth attempt to set it on fire did not have the desired effect either. As the council had taken its official decision, the critical moment had passed.

2. practicing criticality

In the case at hand, criticality consisted in the determination to take everything that the councillor or officials were saying as a subject of research, and to follow the money. It took the collective of parents two years of in-depth research, involving all the legal possibilities to acquire the necessary information, to find out that this specific school had to be removed because it was part of a substantial number of public-school buildings that were going to be sold and converted into apartment buildings. The funds thus obtained provided the municipality with the money needed for concentrating the city’s entire vocational education in three new buildings. The latter may be a worthy cause. The question was why the money had to be found at the cost of public schooling, and at the cost of political and ethical transparency. The school buildings to be sold were often located in urban environments that over the past years had become impressively expensive, due to gentrification and economic developments. The municipality had to negotiate all sorts of agreements with real estate developers, who do not tend to spend public money cautiously and often operate in the shadows rather than in the full light of public scrutiny.

In response, the collective of parents decided to operate in the open. Every step they took was documented on a website: every plan, every letter, all arguments. When at some point the councillor tried to contact a member of the collective (me), and this parent engaged in a personal mail conversation, the parent was corrected by a good friend, also part of the collective, who was able to follow the conversation. And rightly so. It was a mail conversation that, because of its personal character, could easily lead to unofficial agreements, on the side, in the shadows, threatening the very transparency that was at stake. criticality involved the scrutiny of what others were saying and doing, and the attempt to be as open as possible to the critical assessment by others.

3. an ethics of criticality

Though the collective as a whole did not use the term explicitly, criticality proved to be a matter of defining it through praxis. During the height of the struggles, the collective would meet every two weeks, and discuss what to do, how to do it, and what not to do. Few parents involved had read Derrida, but in a sense,all were involved in a process of deconstruction since deconstruction is not something enforced upon something, but is always already at work in something, whether a text or situation. The doxa of real estate development and city council was already deconstructing itself through discursive cracks or contradictions that were made visible in the critical documentation process of the parents. It is helpful to re-read Derrida about the concept of deconstruction, here:

... deconstruction is neither an analysis nor a critique and its translation would have to take that into consideration. It is not an analysis in particular because the dismantling of a structure is not a regression toward a simple element, toward an indissoluble origin. … No more is it a critique, in a general sense or in Kantian sense. The instance of krinein

or of krisis (decision, choice, judgment, discernment) is

itself, as is all the apparatus of transcendental critique, one

of the essential ‘themes’ or ‘objects’ of deconstruction.[20]

The quote helps us first of all to distinguish between critique and criticality. The first connotes the ability to decide, choose, judge, discern. The second connotes the fact that decisions, choices, judgments, and discernments are precisely the object or theme of deconstruction. The core of the struggle for the school was not to prove the municipality or its real estate allies wrong, but to show how the process of decision-making had been full of uncritical decisions, choices, judgments, and discernments. Secondly, it is worthwhile noting that the quote comes from a letter addressed to Toshihiko Izutsu, an expert on Zen Buddhism and Sufism, with a great interest in Truth (Satori, or Enlightenment). This truth, according to Izutsu, cannot be grasped by reason or language, nor can it be taught or understood intellectually.[21] It can only be a matter of praxis and process. Truth can never be discovered, then, although it can be momentarily experienced.

The fight for the school was not a spiritual matter. Or was it, at least in part? If criticality was involved, it consisted in the desire to work towards truth—

a truth that had two modalities. One the one hand it concerned a process of criticality during which, in a certain sense, truth was found: the financial reality of agreements between the municipality, big educational institutions and real estate developers. This truth does matter, as it may (but need not) increase the force of arguments. Yet it remains superficial without the veracity of a process, where truth is not to be discovered but to be experienced. Let’s call this the ethics of criticality.

4. the situatedness of criticality

The specific case stands for a more general state of affairs. On all levels of government, the Dutch state has retreated from public tasks in the context of neo-liberal deregulation, propelled by the idea that ‘the market’ (a fiction) will do things better (a lie).

Critical making, in this context, with its focus on diy modes of making, holds a promise and a potential to serve the needs and desires of a multiplicity of people. In a sense, the entire struggle for the school was a matter of a political diy. If the city council, if the councillor, if all sorts of public officials lack the agency or determination to adequately take care of public matters and public money, this provokes a diy response.

Situatedness is of critical importance. The current form of capitalism is interested in anything that can make the system even more flexible, resulting in less stability for citizens, fewer rights, less care for labourers of all sorts. What is called deregulation often comes down to fuzzy forms of responsibility that make it difficult to follow money flows. The history of the Italian precario bello has been considered as a case in point. When in the seventies ‘playing’ and ‘not sticking to the rules’ became an important tool to deregulate state power, the economic response was that, hey!, playing and not sticking to the rules can be used to reconfigure labourers or employees, demanding them to become ever more creative in ever more precarious circumstances. Consequently, if diy was an instrument of the empowerment of people in the first instance, it also is a form that, in certain situations, can be cheaply appropriated or used as an excuse for more deregulation.

Criticality, in this context, means the full awareness of a situation, an awareness of what is at stake, an awareness of the alternatives one is looking for in a forcefield dominated by others. It concerns the perseverance to critically assess what powers in charge are doing, and requires a practice of transparency that leaves one open to the criticality of others.

representation

Feral Atlas is designed as an exploratory and open journey through an assembled polyphony of materials. Hand-painted watercolours, hydrophone recordings, molecular diagrams, scientific charts, sketches, sound art, and maps made from satellite data and calculated projections sit alongside scientific writing, autoethnography, memoir, poetry, biological modelling, music, video poems, and song. Each element provides an account of the Anthropocene in its own right. Yet when they come together, these diverse elements perform an iterative, multisensuous, and multiperspectival account of how imperial and industrial infrastructures make Anthropocene worlds.

Feral Atlas tries to forge an aesthetic that asks readers to linger over the gathered materials; to tell stories so beautifully that people stop to pay attention to what is going on, and to hold their attention to the scenes of action in which feral ecologies play out. Presenting materials with such absorbing detail, passion, and care that readers might become curious to know more, and in doing so become attuned, able to navigate and orientate themselves within a multidisciplinary array of representational modes.

economy

business

In my own case, I have been working as an artist with business as my medium and material for almost twenty years. My first foray into commerce was with Feral Trade, a sole trader grocery business operating across mixed terrain of art, social networks, and the commodity sphere since 2003 (for a more detailed description, see the entry for feral in this lexicon). I am also a part of the Cube Cola manufacturing partnership that produces and distributes an open-source cola worldwide. The cola is produced in our kitchen ‘lab’ and mailed out to customers in concentrate form; the recipe is freely shared. And I am a member of the accounts team at the Cube Microplex in Bristol, an all-volunteer-run arts venue that makes its living from the bar and the door takings. These endeavours are not proudly independent but rather the opposite, they make and maintain their interdependence with a constellation of other enterprises, from corporates to colleagues. These are the waste collectors, the regulatory agencies, the flavour industry giants, but they are also the corner shopkeepers, smallholder farms, feminist server collectives and diy shipping lines. To mention just a few like-minded endeavours, Company Drinks in London describe themselves as ‘art in the shape of a community drinks enterprise’.[27] They run a yearly production cycle making and trading fizzy drinks in their community, a form of collectivity in art and economy they claim as a new and vital form of public space. And there is the Sail Cargo Alliance, a Europe-wide gathering of wind-powered sailing vessels, ships captains, and cargo brokers who are assembling a grassroots freight system that challenges not only the fuel source but the logic of the whole supply chain, down to what would be traded and why. Critically, these endeavours are not doing art or activism ‘about’ business but are out there in the world doing business for real.

Taking business as a stage and site for experiments in ‘surviving well together’ (in the words of feminist economist J.K. Gibson-Graham),[28] the kind that might open up routes into other possible worlds, may seem counter-intuitive. Those working in the arts or education may have experienced being swept up or perhaps dragged under by a tide of business vocabulary and values, encapsulated in the bonanza of the Creative Industries that reconfigures creativity as a driver of economic growth. At the same time, the uneasy covenant that ‘business as usual’ would maintain a habitable planet has unarguably failed. Yet these fractures and fissures also point to an uncommon potential. business is widely understood and accessible, it operates in and across wildly different collectives, shapes, and scales. It can act as a Trojan horse, an avatar or exoskeleton in which to navigate this hostile yet contestable space that we hazily call ‘the economy’. The sail cargo captains are negotiating with commercial harbours to bring their vessels into port alongside the container ships. The artist-led drinks companies are merging their recipes to produce a trans-national cola with the potential to take down a stickily secretive, world-dominating incumbent. An artist-anarchist farming partnership finds a route through the welfare system to secure the Farm Household Allowance, an income that will bankroll their agriculture experiments for years to come.

In the case of Feral Trade, a few years back I was fortunate enough to be raided by Trading Standards, the UK consumer protection agency. Trading Standards investigates commercial entities that trade outside the law, they have more powers than the police and can for example enter your home without a warrant. They spent hours swarming the Feral Trade website, then cornered me for an interview. After lengthy negotiations, finding no consumer as such to protect—these are peer-to-peer transactions, negotiated entirely through social routes and relations—I received a kind of de facto, state-sanctioned permission to continue trading, in this grey zone of business that Feral Trade has made its home. A tiny island of regulatory indeterminacy, where the relationship between the commercial and the personal is blurred to the point that the law gets a headache.

These are wildly local and contingent examples; they are not models for anything. They are all also imbricated, co-produced and co-dependent with a host of other elements and effects, including the systems they contest. Yet this is also the point. The prospect of business could not be more salient, viewed from the burning debris of a torched economy. We all already are, have, or are in a unit of livelihood, or many—to annex the words of artist Joseph Beuys: ‘everyone is a business’! The challenge, and the potential, is to bring our day-to-day subsistence in line with the meanings we want to make. business could be a vehicle for doing that.

workshop

Our motivation for hosting a workshop on how to give a workshop was mostly to pay attention to the format of the workshop itself as it, so far, has remained mostly unquestioned as a format, even though it is a substantial ingredient of H&D’s activities. H&D is only one of many similar initiatives that resort to the workshop as a format for organizing events. As an ambiguous format, not tied to a specific context, the workshop crosses many boundaries—between art and activism, between different disciplines and institutions, between commercial and educational contexts. My attempt at a definition is: a gathering of a committed group of people who want to learn something together in a set time frame. Workshops that I have been part of usually follow a hands-on approach to learning that can be traced back to the Bauhaus. Here, the workshop was the artisan’s workplace, a place that bridged the divide between making and thinking, as well as between disciplinary divisions such as sculpting and painting. The workshop brought together art and technology in an attempt to provide solutions for the social problems posed by an industrialized, capitalist society.[30]

Workshops like the ones organized at H&D are not bound to any particular space. In this regard they differ from the artisan workshop, which is the site of material production. The workshop does not exclude the possibility for material production or skill transfer and there is a strong incentive to share knowledge and learning experiences through making things. However, making something is not necessarily regarded as a goal. On the contrary, a workshop may become an opportunity to escape the pressure of producing something final or instantaneously useful.[31]

Despite these differences, both the artisan workshop and what I would like to call the ‘ephemeral workshop’ (as described above) can be seen as social spaces within which material-based learning can take place.

Besides methods, techniques, tools, and protocols, workshops also bring about certain social dynamics that evolve from the particular composition of participants, as well as the context and conditions they find themselves in. Such ‘moods’ shift and slide and cause particular forms of production and knowledge to emerge, intervene or evaporate. Workshop participants and workshop hosts together shape and reshape the dynamic present.

In the 1960s and 1970s the workshop evolved as an extra-curricular self-organized activity that resisted principles of art & design schools such as disciplined and canon-based learning, hierarchies between teachers (instructors) over students (apprentices), as well as the commercialization of workshops to produce ‘marketable’ goods.

Since the 1990s the workshop format regained traction with a renewed interest in educational experimentation in the arts.[32] Inspired by movements of the 1960s and 1970s such as the ‘Free International University’,[33] ‘Antiuniversity’[34] or the ‘Non-School’,[35] the so-called educational turn[36] drew attention to collective research, paying attention to processes rather than objects or final outcomes.

Today, collaborative learning, critical pedagogy, and self-organization are still key principles for collective practices that do not abide by the stiff structures of educational and cultural institutions. Workshops organized today for instance by H&D,[37] Varia,[38] Trojan Horse,[39] Anhoek School,[40] or Parallel School[41] continue the legacy of ad hoc self-organization, defiant dilettantism, horizontal and collective learning-by-doing.[42]

However, in our day, the workshop has also become a popular genre that functions well within the framework of a service economy. Situated between work and leisure the workshop’s commercial potential is explored in the context of conferences, incubator programmes, and creative retreats. Taking place outside of the daily work routine, workshops ought to be fun while valorizing the participants’ CV. The workshop has been co-opted by innovation labs and creative agencies and turned into a product itself. For example, Next Nature, a speculative design studio, sells a workshop-in-a-box.[43] Here, the workshop takes on the format of a card game and is described as a ‘2-hour dynamic crash course [that] helps you to better understand and discuss technology’.[44] It might not be intended as such, but in my view this workshop-in-a-box could be read as a satire on workshops, as an ironic commentary on compulsive self-improvement, learning-by-doing and the pressure to participate in one workshop after the other. The implication of presenting a workshop as a product is that the workshop in and of itself is a highly productive format. What a product like the workshop-in-a-box lacks to address is the unpredictability of a workshop context. Workshop moods that are essential to any workshop experience cannot be predetermined thus, cannot be turned into generic instructions that fit on a card.

In my experiencing there is no such thing as a guarantee for ‘a perfect workshop’. Workshop chatter and workshop moods—either friendly and warm or grouchy and agitated—are core ingredients of a workshop situation, but hardly predictable. Still, I do believe that the workshop can be a meaningful tool.

The workshop brings about temporary learning environments, in which making processes but also modes of being together are put up for discussion. Workshop situations have challenged me in my lack of patience or my assumptions of what I regarded as productive or efficient. A workshop cannot be taken

for granted or defined as a given format or medium, and therefore cannot guarantee any outcome. The workshop comes with the potential for confrontation as much as it can lead to long-lasting collaborations and friendships. A workshop situation may produce disruptions and reciprocal challenging of assumptions engrained in disciplinary habits of how we are practicing. Specific moments of transformation are evoked by making things together, in the ‘here and now’.

zoönomy

Zoönomy makes no fundamental distinction between a human economy and economies of other-than-human life. It sidesteps the near-fatal historical mistake of separating human and other-than-human existence. Zoönomy deals with networks of exchange

of matter, energy, and meaning that sustain bodies of

any kind.

Human economic activity should be reconsidered and transformed into a functioning, supportive zone of a larger zoönomy. Consequently, it would no longer be capitalist. Zoöps are a testing ground for putting zoönomy into practice.