Scripting Workshops

The term “workshop” travels through manifold contexts, crossing boundaries between art and activism, disciplines and institutions, commercial and educational contexts. At times, it appears that anything can be a workshop, and it is often assumed that the format is highly productive, where outcomes can be achieved, learned, or produced within a short amount of time. Some workshops draw inspiration from formats and methods that originate in software- and hardware development such as rapid prototyping[1], sprints [2], or hackathons [3].

The workshop has become an attractive format for time-boxed collaboration that functions well within the context of the “new economy,” commercial conferences, incubator programs, and creative retreats. Taking place outside of the daily work routine, workshops ought to be fun while enhancing the participants’ CVs. At times the workshop is understood as a product in and of itself.[4]

Ever since our first workshop-based event under the title “Hackers & Designers” in 2013, the workshop format has played an important role for the H&D collective. Since then, ithas been reinterpreted, practiced, and circulated in many ways and significantly influenced how H&D has evolved as a collective. In contrast to the workshop paradigm described above, H&D workshops are not concerned with products or productivity,to speak in neo-liberal terms. Within H&D, the aim of the workshops is not primarily to fix a presented problem. There are no imposed competitive elements, and processes of making do not necessarily result in output. On the contrary, the artifacts produced during the workshops have the characteristics of disposals rather than proposals. They are the side-products of a process.

Work the Workshop

In 2018, H&D organized the fourth edition of the H&D summer academy (HDSA). For the first time we chose not to differentiate workshop participants from workshop facilitators in our open call. People who were interested in joining HDSA had to apply by submitting a workshop proposal. Thus, they committed to facilitating a workshop as well as participating in the full duration of the two week long workshop program. No prior experience in teaching or facilitating workshops was required. As part of the preparation toward this edition of HDSA, we introduced a peer review process during which the workshop proposals were reviewed by everyone who had submitted a workshop. That way, we involved workshop facilitators in developing one another's workshop preparations and created connections among the group before HDSA actually began.

However, it transpired that the lack of specificity as to what exactly characterizes the “workshop” as a format made it hard to describe, defend, or critique the proposed workshops in a peer review process. The submitted workshop descriptions remained brief. They either reflected on the subject of the workshop or on the technicalities, but rarely did they address both, or in ways that invited suggestions and feedback on the workshop. The proposals did not incorporate descriptions of how a workshop would actually play out in a space and over a certain amount of time, and did not take the different needs and levels of expertise of the participants into consideration. This observation led me to submit a workshop proposal with Shailoh Phillips, who at the time was my colleague at the research consortium “Bridging Art, Design and Technology through Critical Making.”[5] Our workshop took place at the beginning of HDSA under the title "Work the Workshop" and focused on the format of the worksop itself.[6]

We formulated exercises that were meant to offer participants different perspectives on their workshop plans. The exercises were intended to serve as an invitation to view the workshop itself as a medium, something that could be externalized, tweaked, and reiterated. The first exercise, "An Automatic Workshop," was to imagine the workshop as a set of instructions, almost like an algorithm or script that could be executed without the workshop facilitators being present. We also presented this exercise as a script that was delivered without the workshop facilitators being present in the space. We prepared the script and workshop kit in such a way that it explained itself. This exercise was inspired by “THE THING,” an automatic workshop.[7] Writing up a complete workshop script that can be executed without a facilitator present is a tedious process. Aspects of the workshop that might usually be improvised needed to be scripted and explained. Unexpected outcomes had to be anticipated. However, it was also important to leave some space for interpretation and improvisation.

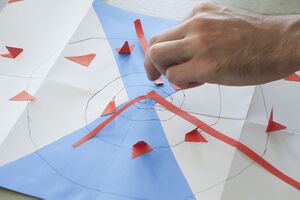

The second exercise asked participants to pay attention to what we called “workshop props”—materials and equipment that frequently appear in workshop settings, such as sticky notes, white boards, projectors, tables, and chairs arranged in a circle, as well as cookies and coffee. First, we asked the workshop facilitators to create an inventory of their most-used props and replace them with other self-made props in order to play out the consequences. The final exercise invited participants to physically rehearse the workshop at a high speed. Workshop facilitators had to physically move their participants' bodies around, in the way they imagined participants would take up space throughout the course of the workshop.

This “meta” workshop about workshops was not intended to provide a recipe or protocol for the perfect workshop. Rather than showcasing best practices, the intention for facilitating a workshop about workshops was to explore the format of the workshop itself as it has become a substantial ingredient for H&D's activities but had remained mostly unquestioned and never clearly articulated. With every new group we have become accustomed to slightly adjusting the ways in which we approach the workshop. We wanted to attend to the ways the workshop format itself can be conceptualized and designed, including unforeseen aspects. Furthermore, we wanted to facilitate an exchange regarding past workshop experiences and expectations in order to find ways of articulating similar and different incentives for facilitating and participating in workshops. As we were all facilitators as well as participants, we had a shared interest in having a discussion about how we wanted the workshops to play out, how we would support each other with feedback, and perhaps how we would take the opportunity to rethink the workshops within their specific contexts.

The way a workshop unfolds depends on many variables that are conditioned by the environment in which it takes place. It was useful to hear about the various workshop experiences and expectations of participants, in addition to articulating collective desires but also insecurities that were specific to that particular temporary group.This was a first step in making individual and collective intentions explicit and in creating a workshop atmosphere prior to and during the workshop program.

In the iterations that followed, H&D continued exploring the BYOW (Bring Your Own Workshop) format as an attempt to decentralize the curation and organization of the workshop program, and to create from the get-go an egalitarian learning environment that responds to the particular assemblage of people, tools, and environments.

In some respects, the practice of inviting workshop hosts to write detailed outlines of their workshop, and letting others give feedback and contribute to their development prepared us for the disembodied experience of organizing, hosting, and participating in workshops from 2020 onwards. The notion of the “workshop script” evolved from a commitment toward paying critical attention to the workshop format but evolved further due to the necessity of staying connected throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. The workshop script became a “thing held in common,” a concept and artifact that was shaped and collectively reshaped, and could be referred to while participants and facilitators were distributed across countries and timezones, and trying to continue to organize, facilitate, and participate in workshops remotely.

Within the context of H&D, the workshop script expresses a particular (not universal) relationship to the workshop format. It explicates the collective effort of staying connected, even while there are other forces at play that seem to work against that effort. By resisting one definition of “workshop,” for instance by including participants, organizers, and facilitators in questioning and redefining the particular conditions of workshops every time there is a new occasion, the workshop as such becomes less “agile,” less of a “panacea,” less adaptable to all and any context.

Publishing workshop scripts

The publication Network Imaginaries was a first attempt to publish workshop scripts. The scripts, developed by workshop hosts of the HDSA 2020 edition, were added to the publication as an appendix. By publishing the scripts in their entirety, we aimed to show the care and attention to detail that the workshop hosts put into their scripts, as well as the manifold approaches to developing collective learning formats. It was an attempt to “open-source” these thoroughly refined learning formats.

H&D generally tends toward free and open-source tools and practices. In H&D workshops, the accessibility of source code offers possibilities for using, copying, studying, and changing, thus learning from and with technical objects. In contrast to the restrictions of using, sharing, and modifying proprietary software, free and open-source principles derive from software development practices where technical objects "are made publicly and freely available." Publishing the workshop scripts was an attempt to make available not just the code that a workshop built on or produced, but also to share the learning formats and approaches, and invite readers to reuse and further iterate on those as well. Yet, what is missing in the approach we took to publishing these scripts in Network Imaginaries was a thorough contextualization of the moments in which they were activated, the particularities of the practices they evolved from, and a more explicit reflection on the ways they played out in further iterations and spin-off projects. Furthermore, we gave the scripts a coherent layout, which rendered them equal rather than showing their diverse formats, aesthetics, and media. The question of how to document, distribute, and circulate these ephemeral kinds of workshop-based practices in meaningful and context-sensitive ways, became a guiding question for the publication you now hold in your hands.

Opening up the editorial process

In May 2022 I organized two workshop series. One took place at Page Not Found in The Hague[8], followed by a second iteration a few weeks later at TROEF in Leiden[9]. These workshops reactivated the “Workshop about Workshop” script and set into motion an open editorial research process that eventually culminated in this publication.

By means of short individual and collective—writing and reading—exercises and discussions, I invited participants to express and put into practice different forms of articulation around workshop-based practice. The workshops generated important insights and informed the process of making this publication in significant ways. That is, this publication tries to move away from a “how-to workshop” approach. It is not concerned with best workshop practices but rather takes into account that the workshop is also a fundamentally questionable format that requires critical attention. Organizing workshops responsibly requires context-specific interrogation of how and within which frameworks a workshop may be organized. This question cannot be answered in general terms. Thus, it must be revisited again and again and is perhaps most pertinently answered according to the terms and conditions of each temporary workshop group, and their particular assemblage of people, resources, tools, infrastructures, and environments. Another important question addressed during these workshops was how to self-organize formats for short-term collaborations and temporary collective learning environments, while also developing relationships that are committed and long-term. Thus, the question emerges of how to balance the flexible and fragmented quality of work and life that prevails in our freelance cultural practices. How do we avoid perpetuating the insecurities and disorientations that come with precarious cultural work, and instead work against it?

Each workshop instance took a slightly different approach and duration (between two and four hours). I reiterated similar prompts, but every time in a slightly adjusted manner and in different combinations. The initial prompts can be found in the scripts published alongside this text.

Insights and findings

All workshops in the series departed from and took into consideration the experiences of the respective group of workshop participants. Participants were designers, artists, cultural producers, educators, students—some had experience in facilitating workshops or workshop-like situations, and others had participated in workshops before but had not yet hosted one.

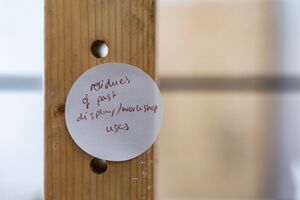

Kicking off the workshop series was Workshop–Werkstatt-werkplaats, which specifically focused on the tension between understanding the workshop as a place for material production and the workshop as an ambiguous yet popular format for time-boxed collaboration. To furnish and equip the workshop space, I asked the collective fanfare to borrow/rent their display system [reference to fanfare contribution]—a modular system made of wooden beams, planks, and reusable screws, which is easy to assemble and reassemble in various spatial structures. As such, the display system can accommodate many hosting situations. With it one can build seating, tables, presentation walls, and shelves.

The workshop participants were invited to collectively challenge / expand / enhance the display system together. As a warm-up, we assembled a “collective workshop vocabulary” on a large sheet of paper, asking ourselves the question how “we” the participating collectives and individuals understand workshop spaces/situations and what we require from them. We individually wrote down memories and reflections from workshops we had taken part in, from activist gatherings to professional training situations. Then we took time to read each other's experiences and read aloud those that stood out to us.

The evolving collective vocabulary served as a starting point for the next exercise: physically annotating the display system. We applied stickers on its “strong traits” and “weak spots,” while taking into consideration the workshop experiences that had been shared beforehand. A recurring subject was that workshops can be intensive, noisy, and overwhelming. Acoustics can implicitly but quite drastically influence the experience of a workshop. Furthermore, the way seating or resting is arranged in workshops rarely takes into consideration the differing physical needs of its participants. Thus, several annotations addressed the subject of accessibility. In the second workshop series we addressed these insights by applying softer materials and cushions to the display system, which served as back rests but also improved the acoustics of the space. Furthermore, we built up the structure in a way that focused on different options for seatingEveryone participating in the workshops had some sort of experience with workshop-like situations. As such, the personal and subjective workshop anecdotes of participants proved generative in the way they tapped into the problems and potentials of workshops. These personal tales were unleashed in different ways. I asked participants to introduce themselves by sharing how workshops have played a role in their work/life. Another recurrent prompt was to write down personal anecdotes in a timed activity (approximately fifteen minutes), which participants placed somewhere in the space that most suited the subject of the anecdote. Participants were then invited to explore the space and spot anecdotes, which were sometimes hidden or placed out of range. Then they read and further annotated them by applying stickers on the space left empty on the A4 sheet. Through the different modes and stages—vocalizing, writing, commenting, discussing—of explicating personal workshop experiences, a vast inventory of stories came into being. The method of writing and commenting on workshop anecdotes proved to be particularly generative as it drew attention to the narrative and discursive potential of the workshops. Through the constraints of time and format (A4 folded in half), participants were able to tap into their personal repository of workshop experiences and unveil humorous tales and memorable insights as much as frustrations and dilemmas.

Interestingly, throughout the different workshop iterations, participants repeatedly expressed discomfort with the neoliberal connotation of the "workshop.”. Alternative terms were proposed, such as “session,”, “meeting,” “event,” or “assembly.” Yet it was challenging to find a term that could accurately express both the ephemeral character of the workshop format and its correlation with the material workshop space—the artisan workshop. That is, the practical, hands-on approach; the emphasis on doing and making that H&D workshops strive for; along with its temporal character, all of which is reflected in both uses of the term “workshop.”

Another prompt, the “forkshop,” posed the question of how workshop-based practices can or cannot be disconnected from their initial contexts, and be continued and appropriated by others—“forked.” In a preparatory email I asked participants to bring what I called a “pedagogical document,” which could be a workshop outline, a how-to, an installation guide, a game play. I also brought a resource pile to work with myself and invited participants to pick a document that spoke to them. For one of the exercises we walked around the space with a document of our choosing in hand, reading aloud bits and pieces from the paper. The goal was to make it sound as if the fragments read out all belonged to the same script. What these documents had in common was their pragmatic and activating tone. Interesting correlations occurred while reading them aloud.

This exercise was followed up by another task which involved working in smaller groups. Participants were asked to draft a workshop proposal by reusing the prompts they had picked. The intention was to consider the ways that workshops—through their methods and approaches—inspire other workshops. It was an experiment in tracing the ways that workshops generate spin-offs, and imagining “workshop bibliographies”as a way to actively acknowledge where these practices originate, and what inspired them.

Lastly, I invited Pia Louwerens to “fork” one of the workshops that took place at Page Not Found. Pia is a performance artist, researcher, and writer who “scripts” play an important role in her practice. Pia has given performative lectures and workshops in many contexts. Within her work Pia often embeds institutional critique and reflects on the artists' role and partaking in what she calls “institutional scripts” These institutional scripts are written and unwritten protocols, rules and expectations that shape the relation between an artist and the institutions they engage with. Pia and I were colleagues at the research consortium “Making Matters,” where we also hosted workshops together. This time I was a participant in my ..... in Pia's workshop.

In preparation for the workshop Pia copied and annotated my script. We had several conversations about how to approach this takeover. Would I—the one who initially developed the script—be there? Would I be a co-host, participant, or observer? We talked a lot about the discomfort as well as pleasure we find in the awkwardness of workshops; how you realize only in the middle of a workshop that it’s not doing its job, and how you feel it by the heat rising in your body.

You may see traces of the aforementioned prompts in this publication. The takeover by Pia, for instance, was inspired by the workshop re-enactment of Heike Roms. The method of forking workshops and workshop scripts led to the cluster “Active Bibliographies,”an attempt to acknowledge and credit workshop-based practices in explicit ways, and to consider their reuse as a way of building a discourse around workshop-based practices. The anecdotal approach of reflecting and discussing workshop-based practices carries through various contributions as well. Lastly, the exercise "How Many Choices" led to the decision to publish the pedagogical documents presented here in a manner that was close to their initial appearance, rather than re-designing them for general-purpose use.

This text contains excerpts from “Workshop Production” in Anja Groten, "Figuring Things Out Together. On the Relationship Between Design and Collective Practice," PhD diss., Leiden University, 2022.