Transdisciplinary: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==transdisciplinary== | ==transdisciplinary== | ||

Feral Atlas | <span class="author">Feral Atlas</span> | ||

The more-than-human Anthropocene is multiscalar, patchy, and overlapping. Its landscapes, its histories, its ecologies do not add together neatly. To study these more-than-human worlds in active formation, Feral Atlas argues the need for situated, multiperspectival accounts that are transdisciplinary in approach, method, and form. | The more-than-human Anthropocene is multiscalar, patchy, and overlapping. Its landscapes, its histories, its ecologies do not add together neatly. To study these more-than-human worlds in active formation, Feral Atlas argues the need for situated, multiperspectival accounts that are transdisciplinary in approach, method, and form. | ||

Revision as of 14:47, 7 March 2022

transdisciplinary

The more-than-human Anthropocene is multiscalar, patchy, and overlapping. Its landscapes, its histories, its ecologies do not add together neatly. To study these more-than-human worlds in active formation, Feral Atlas argues the need for situated, multiperspectival accounts that are transdisciplinary in approach, method, and form.

Centuries of disciplinary precedent have siloed knowledge-making practices, making it difficult for scholars to study entangled Anthropocene histories that bring attention to humans and nonhumans at the same time. The following caricature is over-the-top, and yet it contains a grain of truth: Humanists are severed heads floating in the stratosphere of philosophy, while scientists are toes grubbing in empirical dirt. Even in turning towards the concrete, humanists too often stop with an abstract discussion of ‘materiality’ before we even get to the material. Natural scientists ignore such discussion—but to their peril; uninformed by humanist scholarship on politics, history, and culture, scientists too often grab simplistic and misleading paradigms for measuring humanity. None of these habits allow much in the way of conversation. Without this conversation, the false dichotomy of subservient Nature and mastering Culture continues to be affirmed.

Feral Atlas argues that bringing together theoretical studies and field-based practices in dialogue—often across lines of mutual unintelligibility and difference—is essential for studying the Anthropocene. Feral Atlas contributors describe feral↵ ecologies based on first-hand observation and assessment (including archival materials) each according to their practice. They are biologists, historians, anthropologists, geographers, climate scientists, artists, poets, and writers; their witnessing comes in various forms, from poetry and natural history to the painting of an Aboriginal artist and the memoir of a British professor. Sometimes several reports follow the activities of a particular feral↵ entity, revealing moments of both accord and disconnect. Just as with Anthropocene landscapes, Anthropocene knowledge does not add together neatly either.

During the symposium Making Matters: Collective Material Practices in Critical Times, we (Feral Atlas members Lili Carr and Feifei Zhou) conducted a workshop↵ in noticing feral↵ effects in the area where you live. The workshop↵ took place online and therefore all participants, each coming from different disciplinary backgrounds and based in their respective homes across Europe, observed and recorded feral↵ effects around them, each according to their practices. Sharing first-hand observations formed the basis for a rich discussion during the workshop↵. A selection of recordings is reproduced below.

Feral Atlas is curated and edited by Anna L. Tsing, Jennifer Deger, Alder Keleman Saxena and Feifei Zhou. It can be accessed online at Stanford University Press, www.feralatlas.org.

1. Ann-Katrin Günzel, Cologne. A botanical greenhouse under renovation. Global transport and trade of plants and soils since the early eighteenth century has led to the spread of non-native plant species, pests and disease, many of which have caused world ripping feral↵ effects.

2. Kate Donovan, Berlin. A Detektor (by Martin Howse and Shintaro Myazaki) detects a cacophony of EM radiation beyond human audible range. There is some indication (yet still limited research) that EM radiation generated by human-made telecommunications infrastructures (such as transmission towers, antennas, and cables) has a detrimental effect on certain bird, insect, fish, crustacean, reptilian, mammal, and plant life, while the physical infrastructures themselves have been observed to affect migration patterns.

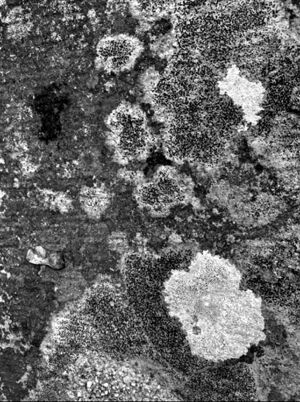

3. Anthea Oestreicher, Karlsruhe. An increase in the variety of lichens observed during the Covid-19 pandemic indicates a fall in particulate air pollution levels.

4. Amsterdam. The installation of EV charging infrastructure underground↵ causes ground temperatures to rise, encouraging the proliferation of potentially harmful pathogens in municipal water pipes.

5. Katharina Wilting, Amsterdam. Tropical fruits are sold at a street market in winter. The palettes on which they are transported overseas harbour non-native insects which, when introduced to new habits, can flourish, and spread.

6. Zeenath Hasan, Copenhagen. The chemicals in rock salt spread to prevent the formation of road-ice is dissolved by run-off and leaches into the groundwater.

7. Amsterdam. A marker indicates that on this site, treatment for the eradication of Japanese knotweed is taking place. Japanese knotweed was introduced to the Netherlands as an ornamental plant in the mid-nineteenth century and spread through Europe’s botanical gardens. It is known to break through concrete and damage roads, building foundations and dykes.

A selection of images and conjectures provided by the participants of Feral Atlas as a Verb @ Making Matters Symposium: Collective Material Practices in Critical Times (Het Nieuwe Instituut Rotterdam, 21 November 2020) and @ Driving the Human Opening Festival (ZKM Karlsruhe, 22 November 2020).