Gestures

gestures

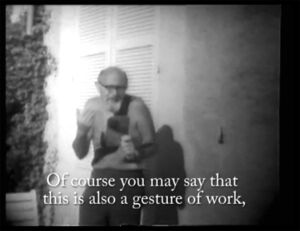

But what would those technical images look like? How might they come to be employed for the critical purpose proposed by Flusser? Luckily, he was able to demonstrate what he had in mind, in a series of collaborations with artists. In experimental videos that he made with the sociological artist Fred Forest, Flusser explored the power of the human gesture as one of the new possibilities for critical human thinking, unlocked through video technology. In the video, Flusser can be seen gesturing avidly as he speaks about gesture. Forest, too, is instructed to gesture with his camera movements, and to criticize Flusser through these gestures. Likewise, Flusser instructs the future viewers of the video to use their own gestures in order to criticize both him and Forest. The viewers’ gestural feedback should then, Flusser and Forest intended, be captured on video, too, and edited into the next iteration of the tape.

This playful exercise is not only a new form of philosophy for the age of technical images. It also points to a more general critique of cultural production. The semantic content of an utterance fades behind the gesture with which the utterance is made. Additionally, this thinking through gestures is patently embodied and situated: It breaks with the enlightenment and modern-age pretension of an abstract, disembodied, pure rationality, embraces contingency, subjective experience, and becomes open for more people. Flusser’s commitment was in tune with his times and various critical revisions of enlightenment rationality in the twentieth century.

It was an answer to the challenge of how to reject disembodied rationalism without also giving up the possibility of critical thinking. This issue had also been explored by his contemporaries Marshall McLuhan

—with his penchant for slang and vernacular—

and Donna Haraway with her leaky neologisms and troubled ironies.

In the gesture, the intent of the utterance and the effects it produces, the experience it generates, is more important than any particular semantic content. In other words, non-verbal communication is more important than verbal communication, connotation more important than denotation. Consider the Facebook algorithm, which allows advertisers to manipulate the emotions of target demographics in real time, as revealed in the 2017 Cambridge Analytica scandal. Advertisers no longer send merely one message lauding their product. Instead, they send a series of messages, which in their aggregation nudge their human targets towards the desired purchases or other behaviour. In the electronic age, the gesture of publishing is thus fragmented into myriad probing moments. As McLuhan quipped, the medium is the massage.

A show in the cybernetic community Alphabetum, ‘Free Emojis’, explored emojis as a contemporary manifestation of gestural communication. What Flusser had provoked his readers with in the 1980s, has become today’s reality. Digital natives are indeed finding that technical images are far more apt for the analysis, commentary, and communication of our experience in the electronic age. Conversely, by observing emoji use we discover that text has not disappeared. In fact, we are writing and reading more than ever before while text has become more explicitly gestural.