Transdisciplinary

transdisciplinary

The more-than-human Anthropocene is multiscalar, patchy, and overlapping. Its landscapes, its histories, its ecologies do not line up neatly. To study these more-than human worlds in active formation, Feral Atlas argues the need for multiple, multiperspectival accounts that are transdisciplinary↵ in approach, method, and form.

Centuries of disciplinary precedent have siloed knowledge-making practices, making it difficult for scholars to study entangled Anthropocene histories that bring attention to humans and nonhumans at the same time. The following caricature is over-the-top, and yet there is a grain of truth in it: Humanists are severed heads floating in the stratosphere of philosophy, while scientists are toes grubbing in empirical dirt. Even in turning towards the concrete, humanists too often stop at an abstract discussion of ‘materiality’ before they even get to the material itself. Natural scientists ignore such discussions—but to their peril; uninformed by humanist scholarship on politics, history, and culture, scientists too often grab simplistic and misleading paradigms for measuring humanity. None of these habits allow much in the way of conversation. Without this conversation, the false dichotomy of subservient Nature and mastering Culture continues to be affirmed.

Feral Atlas argues that bringing theoretical studies and field-based practices into dialogue—often across lines of mutual unintelligibility and difference—is essential for studying the Anthropocene. Feral Atlas contributors describe feral↵ ecologies based on firsthand observation and assessment (including archival materials) each according to their practice. They are biologists, historians, anthropologists, geographers, climate scientists, artists, poets, and writers; their witnessing comes in various forms, from poetry and natural history to the painting of an Aboriginal artist and the memoir of a British professor. Sometimes, several reports follow the activities of a particular feral↵ entity, revealing moments of both accord and disconnect. Just as with Anthropocene landscapes, Anthropocene knowledge does not line up neatly either.

During the symposium Making Matters: Collective Material Practices in Critical Times, we (Feral Atlas members Feifei Zhou and Lili Carr) conducted a workshop↵ in noticing feral↵ effects in the area where you live. The workshop↵ took place online and therefore each participant, all coming from different disciplinary backgrounds and based in their respective homes across Europe, observed and recorded feral↵ effects around them, each according to their practices. Sharing firsthand observations formed the basis for a rich discussion during the workshop↵. A selection of recordings is reproduced below.

1. Ann-Katrin Günzel. Luxembourg. A botanical greenhouse under construction. Global transport and trade of plants and soils since the eighteenth century has led to the spread of non-native plant species, pests, and disease, many of which have caused world-ripping feral↵ effects.

2. Kate Donovan. Berlin. A homemade receiver detects a cacophony of EM radiation (beyond human audible range) emitted from telecommunications infrastructures. There is some indication (yet still limited research) that EM radiation has a detrimental effect on bird and insect life.

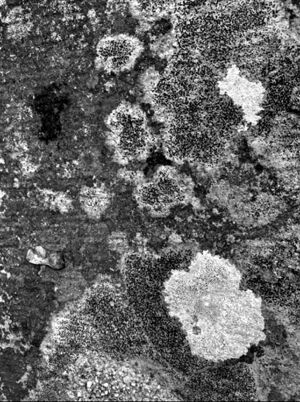

3. Anthea Oestreicher. location. An increase in the variety of lichens is observed during the Covid-19 pandemic, indicating a fall in particulate air pollution levels.

4. Lili Carr. Amsterdam. The installation of EV charging infrastructure underground causes ground temperatures to rise, encouraging the growth of potentially harmful pathogens in municipal water pipes.

5. Katharina Wilting. Copenhagen. Tropical fruits are sold at a street market in winter. The pallets on which they are transported overseas harbour non-native insects which, when introduced to new habits, can flourish and spread.

6. Copenhagen. The chemicals in rock salt spread to prevent the formation of road-ice is dissolved by run-off and leaks into the groundwater.

7. Lili Carr. Amsterdam. A marker indicates that on this site, treatment for the eradication of Japanese knotweed is taking place. Japanese knotweed was introduced to the Netherlands as an ornamental plant in the mid-nineteenth century and spread through Europe’s botanical gardens. It’s known to break through concrete and destroy roads, foundations, and in the Netherlands dykes, which are the structures that keep the sea out. Damage amounts to millions of euros per year.