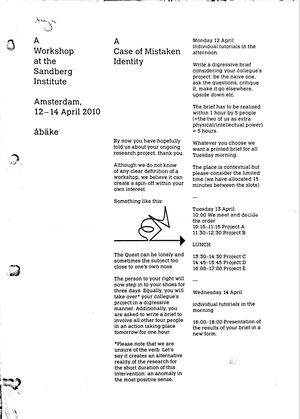

A case of mistaken identity

- In August 2022, I, Anja Groten, reached out to Maki Suzuki, a member of the collective åbäke, with the request to republish an assignment I had received from him and Kajsa Ståhl at the workshop "A Case of Mistaken Identity,” held at the Sandberg Instituut in Amsterdam, 2010. I have kept this document with me ever since. My request sparked the following conversation.

- Anja Groten: Twelve years ago, in 2010, we met at a workshop in Amsterdam. I recently reached out to you with a remnant from that encounter, an A4 workshop assignment that you handed out to a group of design students at the Sandberg Design Department. I’ve kept this paper with me, stacked in a pile of pedagogical documents consisting of how-tos, scores, assignments, gameplays, and installation manuals. This pile is an important resource for me and it holds all kinds of stories. I would like to open up the story box of this one particular workshop assignment with you. So, to begin: Do you still host workshops? What do you think about the ambiguous format of the “workshop,” and its role and function for art and design education as well as for collective practices, such as H&D and åbäke?

- Maki Suzuki: Kajsa has stepped back from teaching for now but I have kept up this practice. After teaching for seven years at RCA, another seven at HEAD Geneva, and five at Open School East, I finally realized that the week-long workshop is my favorite format. As to your question about its role in art and design education, I think it depends; the workshop can be anything from a confusingly vague system to a brilliant flux of energy in a diverse curriculum. Some schools possibly have too many workshops, while others have too few. I think it is always complementary to have the curriculum of regular teachers setting up year-long programs offering longer term support for student's study trajectories. I have lost patience and fire on this and prefer the sprint-like workshop with its near immediate deadline to fuel a positive boost. The workshop you mentioned is key in my practice of workshops, which we started being invited to host almost immediately after graduating from RCA, meaning that we were then not much older than the students we met in those early years. Until 2012, our workshop briefs were written contextually to what we thought we knew of the hosting school, or the parameters we were made aware of. For instance, in Valence, we knew the school was close to a fascinating architectural oddity—Palais Idéal du Facteur Cheval—so we made sure to include a bicycle trip to the place. At Jan Van Eyck, the workshop took place on labor day, so we proposed a reflection on the concept of the “three-eight” (eight hours of work, eight hours of rest, eight hours of leisure). In St Etienne, we knew there would be a large group of eighty students, so we proposed a workshop about power structures, uniforms, and democratic decisions.

- AG: This question of workshop momentum is really interesting. Workshops as temporal collectives can create momentum, and disrupt routines and conventional ways of doing and making. But I also recognize what you said about workshop fatigue. I like that you speak in terms of thresholds. Speaking as someone who regularly hosts/participates in workshops there is a moment when there are too many workshops, or the workshops become too long. And there are definitely moments that I feel too exhausted to host and join them as well. I seldom do full-week workshops. This happens perhaps once a year, when three or four of us from H&D get a chance to hang out in an unusual place together for a full week without distraction, which is difficult to arrange with the fullness of our day-to-day schedules. So while we might be invited with the intent to distract people from their daily routines, for us, an external invitation to host a workshop is actually a way to sustain some form of continuity. During such workshops we often build on something that someone from the collective has experimented with in past workshops—perhaps an experimental publishing tool, or a Wi-Fi module that can be hacked and repurposed, or a battery-powered toy that can become a drawing tool. Often these technical experiments and prompts have been pieced together by a set of people from the collective and are then picked up by another group and continued. Existing documentation is tweaked and improved, while being grounded in the respective workshop environment. Working in this way, asynchronously and in a decentralized manner, is also a way of strengthening collective ties.

- MS: Yaïr and I are interested in how the supposed distraction of how, for example, someone performing a text that was written on a roundabout and surrounded by cars, can have consequences for a student studying jewellery, and how those methods can be translated from one field to another.

- MS: In 2012, I was invited to do a week-long workshop to which I invited choreographer artist Yaïr Barelli to participate in something we named “Le Magnifique Avventure.” We decided to extend the workshop hours to last the full week—including nights—from Monday morning to Friday evening. The driving force was guided by the individual wishes of the participants, and realized collectively. The first edition involved a whole group of students and two tutors walking around Leman lake in the Alps. One student suggested we repeat this every year, and we have done so ever since, for ten years running, with different institutions and self-initiated contexts.

- AG: Yes! I read the script in the book Taking a Line for a Walk (eds. Nina Paim and Emilia Bergmark). Such a good brief! It also makes me think of the ways in which you situate workshops, as you say, in a location, community, or according to the vibe of a group. It requires quite an open mind as well as generosity, a sincere interest in the specific context and that you—as the workshop host—are also a guest in that context. Scripting a workshop does not really work with such an approach. I’d imagine it requires being in the moment.

- I assume your approach also only works with active participation. There is no possibility to engage at 50% as a participant. It requires commitment from all sides, as you said. Have there been instances when this was not working?

- MS: Absolutely, it’s not for everyone. In the first edition we didn’t need to specify this as our workshop was one option out of seventeen that the students could choose from. We are now very careful to mention that this cannot be a mandatory workshop. That being said, I am typing this while having breakfast in a hotel in Pristina after an intense week-long workshop with graphic design students of EKA Tallinn. It was mandatory for the first years and an option for the second years. Everyone came. We organized a road trip from Estonia to Kosovo where we were granted a slot in the lecture program of REDO. The aim of the trip itself was to generate content for a performance that took place yesterday, accompanied by a publication, which was printed on the road; merchandise; and other texts and songs. We became a circus, a band. It’s still fresh but I recall there being a human pyramid, songs played on the guitar, belly dancing on stage. I love that these people were brave enough to perform just after Laurenz Brunner. Performing is unusual in the practice and study of graphic design and discomfort is an element I welcome in these contexts. Failure is essential to work through.

- An art school is by definition a paradoxical educational context. Am I wrong to think that during our studies we are gradually learning not to do what we are being taught, and instead bloom into a practice that questions the very foundations of our education, as well as the courage to find one’s voice?

- AG: If so, in what contexts do you host workshops, how frequently, and what do you like about hosting workshops?

- MS: The invitations first came from graphic design courses, which is also where we started out from. As our practices evolved and opened up to collaborations, invitations started to arrive from design colleges (graphic, product, architecture), art colleges, and dance institutions. The intensity of the week-long workshop and the full commitment it demands, both intellectually and physically, would make one workshop per year enough, but the frequency depends on the invitations. At this very moment, I'm preparing for a few workshops all taking place in the next few months, which is a bit much.

- AG: My second question derives from the document itself. I was wondering about this format—or the graphic design genre—of the workshop prompt: its material, aesthetic, and pedagogical qualities. You designed this document in a very particular way. I am curious to hear about the considerations you took while making it. What makes a good workshop assignment sheet in your view, in form as well as content? What is its role and function in a workshop and/or the preparation for the workshop?

- MS: We used to enjoy designing the briefs as the form can never stray too far away from the question of content. They might be hints or red herrings. They also direct, but the reality is that the real experimentation comes from a process that one cannot foresee and therefore is not necessarily contained in the design itself.

- AG: Related to the previous question, I’m curious to know how you usually design a workshop. What considerations go into its planning? How much is predefined? How much of it is open?

- MS: The workshops I am interested in hosting don't have an agenda on techniques or skills needed. My role has become about listening to what the students want and making sure they approach it in a radical way.

- AG: Yet I feel you propose quite a distinct approach, a way of doing workshops and encountering new people. Perhaps it’s an approach that resists container definitions such as “technique,” or “method.”. But I think this role of “active listener” should not be underestimated, especially in the field of design and design education, which is perhaps more often about building up strong egos and individual signatures. This more responsive or mutualistic approach to designing / facilitating / planning is much needed.

- MS: Yes. Listening comes first. Listening to what an individual wants. Our role is often to push them further in the direction they chose. Sometimes it is revealed that they took the wrong direction, but this is also fine because changing one’s mind can provoke new thoughts and produce strong results.

- Can one be radical in a moderate or mild way?

- With regards to skills or techniques, my points of reference are instilled in my practice. I am not very good at anything but I am happy to perform, dance, or make a piece of furniture, though I hope no one commissions me to design a bridge. I rely almost always on collaborations and by finding people whose skills are highly superior to my own. The results always come from this interaction. However, during a workshop we don’t have the time to find someone else and therefore look within the group. The workshop I mentioned previously included a semi-pro gymnast and a guitar player.

- A more important reason for not organizing skill-based workshops is due to the fact that I want to participate and learn things myself, which is easier when I am not expected to impart knowledge about something I already know.

- AG: What makes a good and what makes a bad workshop? What are your thoughts on workshop results?

- MS: In the past, I would have said the immediate satisfaction or a new learning would be the reward of a good workshop, but I am no longer sure about this. It seems to me that the commitment and excitement itself is its own reward. If one is bored or not curious, then the workshop is bad. This goes for the tutors, too. As for workshop results, I am always up for producing something or having an output. Objects, performances, and doing something public is exciting but I also follow what the students choose, and on many occasions they decide it’s not relevant to share the results with others. In 2020, during the lockdowns, we decided to write a book during the workshop that ran across fifty-two Fridays. This may be the most concrete result of this series of workshops.

- AG: Thank you for this. What you said about excitement and curiosity also from the side of the tutors reminds me of the work of bell hooks who wrote about the wellbeing of the teacher, and their process of self-actualization. For me, this usually happens when I get to explore new and unknown things together with students, workshop participants, or collaborators. Curiosity also means not-knowing everything before you propose it in a class or workshop, which keeps you alert and receptive to different viewpoints. When I was a student, I always found it most inspiring when tutors were figuring something out in front of the class, like openly thinking through things, or fixing a bug in code. These were the moments I felt really connected and could actively participate in the learning experience.

AG: Hosting or guesting? As a workshop host I enter an environment like an external force, intervening in their daily routine, and then leaving. Often, I am not there when things begin to resonate, when the content of the workshop takes effect in someone’s work, their thinking, and their evolving practice. Do you have any stories, examples, or tactics of how you deal with building longer-term connections? How do you stay in touch with workshop participants? Or perhaps it’s not important to you?

- MS: I have been teaching for twenty-two years, ever since I graduated, which means the likelihood of meeting my former students is rather high because the western art and design world is small. There is opportunity for feedback in those encounters, and occasionally I receive a heart-warming email like your own. I am quite good at keeping in contact with ex-students, because we have probably shared a meaningful experience together, something that Le Magnifique Avventure has often engendered.

- AG: Yes, and it is often only in retrospect that a workshop starts to resonate with its participants, the memory and residual effects of this shared moment. In the case of your workshop at Sandberg, we obviously had a good time. It was productive and fun and interesting. But afterwards, too, it was frequently referred to by students, and it has continued to shape up, influencing everyone’s projects and learning situations.

- While studying in art and design schools, students are approached as individuals—rather than as a collective. They are assessed as individuals, receive individual student numbers, individual key cards, work on individual research projects, write individual theses. The A4 handout "A Case of Mistaken Identity" reminds me of this powerful moment of being given permission to approach and apply myself actively in the work of others, and simultaneously being able to hand over the burden of my individual project. How do you feel about the role of collective practices within the history of design and design education? What inspired and enabled you to work collectively within a field that is still rather occupied with individual signature / authorship / iconographies?

- MS: I am part of a collective and have been since I graduated. However, you will have noticed I no longer use the collective "we" as the four of us who make up åbäke mostly work independently (we live in London, Stockholm, and Copenhagen). Ten years ago, we were part of a group show in which we explored the different collectives we were or had been involved with.“The Inventory of Aliases” was a residency at Somerset House during which we had moved our entire studio for a couple of weeks to the gallery and changed the setting and activities every day according to the different collectives we participated in (this was fourteen at the time). Today I enjoy being part of temporary collectives, those that last sometimes for no longer than a week-long period, while others have lasted years. Ultimately, I feel this is true of each project and includes all participants such as curators, producers, printers, advisors, designers, anyone met during the research, etc.

- AG: It is an important nuance to make, to problematize the “we” when speaking about collective practices. I definitely fall into the trap of assuming a “we” sometimes, especially when I fail to explain how the collectives I work with operate. Often people have the desire to “start a collective,” which, in my experience, never works. The collectives I work with all evolved organically, they weren’t started with the intention of becoming anything. And they are also quite unique in their ways of organizing, forms of expressions, and conducts. I feel that the “we” somehow flattens those nuances, particularly due to the fact that all of us are involved with multiple collectives, organizations, and collaborations. I also feel that collectives are quite permeable, receptive, and vulnerable to the context they evolve in. As I understand the way åbäke is organized, it is perhaps comparable to how we organize H&D. You are a distributed assembly of people and practices and as such quite flexible toward new conditions. We did not anticipate for H&D to go on for such a long time, but I think because nobody worries too much about it continuing and nobody fully depends on it, H&D can in fact continue.

- MS: [Laughs] What you are describing is brilliant. Not caring about continuing as a collective will probably be the reason you will. Taking it too seriously could be the reason for breaking up. Also, it is fine to finish collaborations.

- AG: Do you have any other workshop scripts you'd like to share?

- AG: Thank you, thank you! I was wondering about the collaboration with Yaïr Barelli on "Le Magnifique Avventure.” It was your first collaboration together, right? You had not worked together in that way before? I am asking because I feel that organizing a workshop together is a nice way to get to know each other and to start collaborating. Did your collaboration continue afterwards?

- MS: Yes, it was a nice way to get to know each other after we had collaborated as part of a group show. The first workshop was so strong that we decided to do it once a year for ten years. Ten years have since passed, so we extended it so that we do it once a year until we both die. This year we will do two, one in Zürich and one in Poitiers, both at art schools.

- AG: Why do you spell it "avventure," with the double vv?

- MS: The title comes from two movies: Le Magnifique and L’Avventura.

- MS: Now, two questions: What is the difference between a tutor and a student? How does one keep the privilege of being a student?

- AG: I actually brought your questions to my class last week and asked my students about it. We are just starting this course which considers the classroom as material to work with, to iterate, test out, and challenge. Students are organizing collective learning situations throughout the year. The class will be about the things they want to learn about, so they will play the roles of teacher and student at the same time. It was their first class so we first had to understand what the difference is between tutor, mentor, lecturer, professor. Everyone comes from entirely different learning environments and has different understandings of how studying takes place.

- In the context of Sandberg, we don't really have tenure professor style teaching positions. We are all broke freelancers [laughs]. So it was good to clarify this to students from Germany, for instance, where professors have lifetime positions.

- I think we could all agree that as a “teacher” you want to be in a position of a learner as well. You want to figure something out through your class. It makes you curious as a teacher and open to other perspectives. Yet there is also a difference between being a student and being a teacher. In our case, we discussed that we want to consider the position of the teacher as a facilitator, as the one mediating the process, and of taking care of the time and space we share. I definitely recognize what you said earlier, about actively listening to students and supporting them in what they want to do. I would add that I’d like them to be able to develop a critical attitude toward their own and other’s work, as well as their positions as makers. I’d like them to achieve a level of comfort together where everyone can pose uncomfortable questions, and self-critically reflect, ask questions, and problematize their work and positionally without giving up, and without losing joy and self-confidence. I think the privilege of a student-mindset is that you are never self-satisfied; you always aim to do better.

- How to keep the privilege of being a student? Obviously it helps to be curious, ask questions, and always stay in the mindset of wanting to learn new things and challenge yourself by entering new environments, trying new tools, languages, dance moves, you name it. I like to learn in company, in the presence of others. It gives me energy and joy. It keeps me sharp. I like to learn new things not to become better, but to keep an open mind and be comfortable in the position of not-knowing something.

- MS: Thanks Anja.

- AG: Thank you, Maki!

- Maki Suzuki (FR) is the co-founder of Åbäke, a transdisciplinary graphic design collective founded in 2000 with Patrick Lacey (UK), Benjamin Reichen (FR), Kajsa Ståhl (SE) in London, England.