Babanton

babanton art

the good neighbours agree to always agree

Babanton is a game. It is crucial to understand the gameplay. First, from its terminology: in Sundanese, ‘help’ (Indonesian: bantu) is translated as ‘banton’, but the word babanton contains a repetition of ‘banton’. It means the help is reciprocated, like in a game. babanton is a societal value in Jatiwangi. As a game, it starts from individual needs. In neighbourhood social practices, as a good neighbour, it is a social obligation to help a fellow neighbour who is having hajat (event, ceremony, errands). Therefore, we need to sacrifice our ‘time’, even if it’s work time. It subsequently establishes a social ‘currency’ that uplifts our dignity as people living in a community. A help from our neighbour, as a currency, may be exchanged in times of need.

JaF artistic practices engage with the spirit of the community’s babanton. In the early days of JaF, many initiations or art projects were nothing but but hajatan presented by JaF that were held by Arief Yudi’s family—a distinguished family in the village (his brother Ginggi was the Village Head at the time). The neighbours acted as good neighbours to do babanton in the artistic activities, whether they understood them or not, needed them or not. What they knew was that the neighbour was having a hajat and was in need of help. Afterwards, automatically, JaF would also be involved in this mutual assistance game by being a good neighbour, from providing a sound system and a stage on a neighbours’ hajat, designing logos for neighbours’ products, making or editing videos, documenting pre-wedding photos, to merely fixing printers. One time, Ginggi blurted, ‘Any talk of art in society without ever helping a neighbour’s hajat or attending a neighbour’s funeral is utter baloney.’

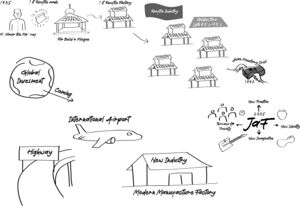

Let’s imagine that JaF’s neighbours are also other community members, local governments (at least Arief Yudi’s schoolmates or Ginggi), roof tile factory entrepreneurs, police, and other institutions. Then, automatically, they will be involved in the babanton arts that manifest in the ever-expanding collective artistic practices, in which tanah is exalted within. This interplay between art and babanton enriches them both; art expands the babanton practice into not just an individual matter—celebrating a marriage or making a house is being turned into larger collective works. On the other hand, babanton restores art to an important position in creating the imagination and action of a living space that is good for collective life.