CriticalMaking

critical making

Critical making has a cultural and material affinity to maker culture and simple-to-use digital technologies (such as Open Source software, social media and 3D printing) that are thought to foster

a culture of ‘diy citizenship’.[3] In critical making, these technologies are not only used to bridge thinking and making, but also to introduce elements of design education into social sciences at universities.

Critical making knows at least three different definitions and schools:

- critical making developed and practiced in and for social sciences at the University of Toronto by Matt Ratto and his research team;

- critical making as socially engaged maker culture, practiced by Garnet Hertz and his research team at Emily Carr University in Vancouver;

- critical making as a design ethos, proposed and practiced among others at the Rhode Island School of Design.

critical making in social sciences

by ginger coons, who completed her PhD research in the critical making Lab of University of Toronto:

critical making, in this school, is a practical study and research method for students and scholars with no art, design or engineering background to do part

of their classroom study through material experimentation instead of only reading and discussing texts.

Open Source and Internet ‘maker’ technologies dramatically lower the threshold for non-experts

to build something—an object, a piece of technology, an application—to serve as a temporary, experimental, and discursive device for studying and exploring a concept or theory.

A cultural studies or feminist theory class, for example, could use critical making as a classroom method to study and discuss the claim of the African American poet and critic Audre Lorde that ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’,[4] by practically experimenting with the possibilities and limitations of using corporate social media platforms such as YouTube and Instagram

for anti-corporation political activism.

critical making as socially

engaged maker culture

in more than forty countries. From the perspective of digital media artists, ‘maker culture’ boiled down to

a mainstreaming and commercialization of radical technological diy that had existed from Nam June Paik’s self-constructed video synthesizer in the 1960s to, among others, artists’ experiments with self-built radio and tv infrastructures in the 1970s and 1980s, and the ‘tactical media’ movement of the 1990s.

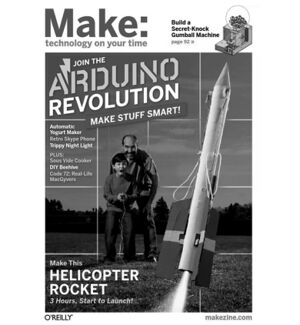

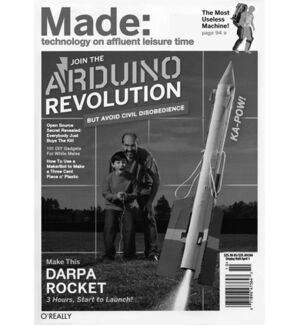

This difference in politics is epitomized by a cover of Make: magazine (vol. 25, 2011) and its parody, Made: by the designer and artist Garnet Hertz (2012):

In a series of freely distributed and freely downloadable critical making zines, Hertz positions critical making as an umbrella term for any art and design practice that experiments with technology in critical or non-mainstream ways: from the post-punk robotics of the 1980s Californian Survival Research Labs collective to ‘tactical media’ art like the political graffiti-spraying robots of the Institute of Applied Autonomy, the ‘critical engineering’ of the homonymous collective around Danja Vasiliev and Julian Oliver, to the critical design of Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby (which Ratto differentiates from his own concept of critical making).

critical making as a design ethos

Since Ratto nevertheless brings ‘making’ into university classrooms, it is not surprising that design educators conversely reclaim critical making for their own practice, in the broadest sense of the term. An example of this is the 2013 book The Art of Critical Making by the Rhode Island School of Design in which the school refers to its entire curriculum as critical making.

epilogue

references

INC Reader 12. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2019, research.hva.nl/en/publications/fe892f5e-c7b9-4a1a-9b76-1674562d56f0.

pp. 252–60.

and Social Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014.