Solarpunk Postscript

An incomplete collection of resources and prompts curated, edited, and commented on by Loes Bogers

There is no cloud, just other people's computers. Virtual reality is as real as the hot air blowing from a server farm. While the effects of the global climate crisis are becoming increasingly visible, in both media representations and our everyday experiences, efforts to change course and radically remake the ways we create our own surroundings and the infrastructures we depend on are slow, too slow.

Computing is and has always been material in essence, but, for many of us, our relationship to computing has become obscured from view. How can we resist compliance with the unsustainable status quo of digital computing and electronics? What tactics could help us to engage in a more sustainable approach to computing? What thinking models and approaches could help us to curb the extractionism, colonialism, and solutionism associated with contemporary digital systems design?

By carefully selecting and bringing together different resources from the fields of literature, movies, academia, design, the arts, and computing, this compilation hopes to offer and inspire possible outlooks for (more) sustainable and equitable computing practices.

A digital version of the first iteration of this list will be shared on Github. It is the start of an evolving list that can grow with time. Readers are invited to contribute task suggestions (of circa 300 words each) to the compilation. https://github.com/hackersanddesigners/SolarpunkPostscript

Some shared tasks:

- Deconstructing “expertise”

- Untoolkit

- Peel your eyes for ambiguity and amplify greyness

- Apply lightness, liberally

Deconstructing “expertise”

Specialist knowledge of computing is primarily relegated to the fields of engineering and computer science. From early conceptions of mechanical general purpose calculators to wartime computing embodied by the ENIAC, computing is often told as a story of (Western) scientists. Understanding the ways that "experts" are socially and culturally produced within a field can help to demystify the exclusionary mechanisms that define the insides and outsides of any discipline. Carolyn Marvin traces the rise of the electrical professional in the early 20th century, and points out that unlike civil engineers and mechanical engineers, this new group of professionals lacked the almost aristocratic veneer provided to the former professional groups, whose practitioners stemmed from the higher strata in society.[1] Electrical engineering journals were more popular in tone and quoted from lay press as well as academic sources. In doing so, they catered to foremen, designers, and entrepreneurs in the field, not just to scientists and engineers. Over the course of the 20th century, electrical engineering was able to re-establish itself as a prestigious discipline at the level of other fields of engineering and science. Marvyn traces the development of its “textual communities” to articulate how any claims to electrical expertise were gate-kept through textual processes, such as jokes targeted at rural, female, colored people.[2] Marvyn’s discourse analysis still offers a compelling read, and her methods can be useful tools to help deconstruct today's computing expertise.

Proto-computing practices do not just exist in Western scientific histories, but can also be identified in what might also be called “craft practices.” Matti Tedre and Ron Eglash define what they call “ethno-computational practices” as those practices that (formally or informally) include:

- data structures: models and ways of organizing and representing information;

- algorithms: ways of manipulating organized information in a systematic way;

- physical and linguistic realizations of such structures and algorithms in the form of tools, games, art or other.[3]

Through this lens they are able to identify and acknowledge alternative ways of knowing computing, such as Inca Quipu, Ashanti board and pebble games, and the intentional design of fractal geometry in African architecture and hair braiding practices. Sadie Plant's feminist manifesto Zeros + Ones weaves together histories that connect women to the development of computing, and in doing so highlights sensory ways of knowing that stem from textile production.[4] Visiting unchecked narratives can help to open up space for more ways of knowing, and undo some of the unquestioned disciplinary boundaries that have been put in place and solidified over time.

- Prompt: Meet your friend from another discipline. Swap your work computers. Open each other's email clients and pick an unanswered email. Draft a response. What can you gather from each other's methods of knowing and not knowing?

Untoolkit

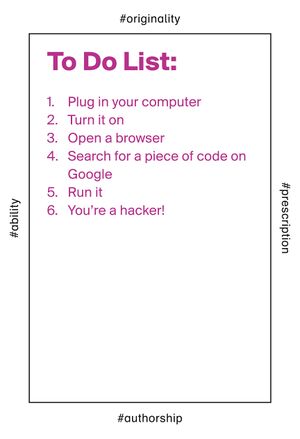

To do list:

- Plug in your computer

- Turn it on

- Open a browser

- Search for a piece of code on Google

- Run it

- You're a hacker!

- Matthias Tarasiewicz, Sophie-Carolin Wagner, Moritz Greiner-Petter, and Felix Gerloff,Unmaking: 5 Anxieties, Proceedings Transmediale (2016), 11, https://www.academia.edu/32875905/Unmaking_5_Anxieties_IXDM_and_RIAT_Transmediale_2016_

You might be thinking: Haven't we already demystified computers in so many ways? I can open an Instructable[5] to set up my own server in 12 easy steps,[6] or find a blog describing how to solar power my Arduino project with a Sparkfun charging board.[7] Maybe from there we can open another line of inquiry and experimentation. In your set up, which elements are in fact pre-designed toolkits that you depend on and could unpack further? The Arduino in your hand feels like a singular, cohesive object. Take any of the following tools to highlight its modularity and connectedness to other infrastructures, social rules, and systems. A loupe brings into view the shapes of the teeny tiny components on your chip, and sometimes even a number or factory code. What is it? What does it do? What shapes, sizes, and formats does it come in and what unspoken rules are behind those shapes and sizes? What materials are involved in making it and where do they come from? How do these relate to the software environment you use to make the chip read and do things? How is the software interface connected to text files in the deep folder structure of your computer? Where does the software refer to something tangible you can find with your loupe, and why? What is the relationship between the abstract representations offered in a component's datasheet and the physical object in your hand? Unpacking any computer will bring out an infinite number of relations up for interrogating, interrupting, and intervening. By virtue of seeing and feeling the relationships you are offered opportunities to change the engagement. An insightful example of a process of making an “untoolkit” is described in "Microcontrollers as material" by David Mellis et al., at MIT Medialab (2013).[8]

The field of wearable computing and soft circuitry offers a wealth of examples that imagine other ways of relating to computing. In the process of trying to make hardware softer to the touch, practitioners have sought out alternative materials and modes of connecting those materials. Hannah Perner-Wilson's Kit-Of-No-Parts: Recipes for Materially Diverse, Functionally Transparent and Expressive Electronics opens up further exploration and material investigation of electronics, instead of the straightforward replication implicit in most electronics design.[9] Irene Posch and Ebru Kurbak's handcrafted and functional Embroidered Computer explores the history of mechanical relays, which dominated computing before the invention of semiconductors such as transistors, and make a compelling weaving of historic embroidery knowledge and 8-bit computers.[10] More broadly oriented and more recent, is the research project Feminist Hacking: Building Circuits as Artistic Practice by Stefanie Wuschitz, Patrícia Reis, and Taguhi Torosyan.[11] This project looks into ethical and ecological issues connected to computing hardware, such as mining semi-precious materials in developing countries, and aims to ground media art-making in fair practices of hardware production. Engaging with computing as a fundamentally material practice offers the possibility to rethink the terms of engagement between different materials, histories, and systems.

- Prompt: Meet up with a bunch of friends with different skills and knowledge. Open up a broken computer or other device and explore what's inside, try to identify some of the elements and components you find. Can you zoom in further or is this the smallest possible element you can identify? Pick one each (or work together if you prefer), and research how and where it is made, what it is made of, and where the source material can be found in the world. Is there a way to make a functional element from scratch from alternative materials? Document the process and share it with each other.

Peel your eyes for ambiguity and amplify grayness

Computing is a form of mediation between beings and materials, brought about by means of abstractions and numbers. These systems of abstractions we live with and by are designed to disappear into the background of our daily rhythms. This is a result of deliberate design and intentional engineering acts, justified by arguments that speak for intuitive interaction, efficiency, and usability. Questions such as “Is this technology bad?” are only of limited use. Google's code of conduct might mention "Don't be evil," but this is an empty phrase. Nobody would disagree with such a statement. As Matthew Fuller and Andrew Goffey convincingly argue,[12] this phrase implies that even if people involved are good, systems can still do evil, they incite and provoke, twist and bend, leak and manage. It's the infuriating reality of well intended but naïve creations, with unintended consequences on top.

To parse the complexity of our socio-technical world and undo occlusions in these systems, Matt Ratto and Garnet Hertz suggest a number of strategies under the term “critical making.”[13] Firstly: identify metaphors and assumptions that guide and shape a discipline (see also Deconstructing Expertise), such as efficiency, convenience, and pervasive connectivity. Secondly: recognize what these values and metaphors exclude or marginalize. How can we see what is meant to be invisible? Keep your eyes peeled for blandness and ambiguity—or grayness—and amplify it. Scrutinize what is bland and unexciting, "Grayness is a quality that is easily overlooked, and that is what gives it its great attraction, an unremarkableness that can be of inestimable value in background operations."[14] In 2013, artist duo YoHa invited fifty-one artists to choose a gray object and describe its exclusionary power. From ASCII character set to Zero-hour-contracts, the texts shown as part of the Evil Media Distribution Centre highlight a wide range of directive objects forming the background of contemporary society.[15] The texts in this collaborative work are somewhat similar to the third and last move, of making found occlusions legible. This might be in textual form, or occlusions might be inverted by bringing the exclusion to the center, and then building and deploying an object that embodies this reversal. A notable example is the project SeatSale by Steve Mann: a physical chair that highlights the way digital rights management (DRM) systems create artificial scarcity. Such software allocates "seats" to limit the use of a software license, which took the shape of a mechanical chair with spikes in the seat that can be lowered and lifted depending on the amount of "seats" occupied on the license.[16] Whether textual or object-based: amplify the grayness of systems to render their evil doings in legible form.

- Prompt: Locate a resource that claims to explain an aspect of computing. A title like “How Computers Really Work” or any other indication of authoritative helpfulness is great to look for. Pick an aspect of computing that seems excessively boring, and articulate what written and unwritten rules are at play to make the subsystem function. Imagine and describe, visualize, or build a scenario where you introduce another interpretative layer into that system. Remember that computer things "work" by means of excluding ambiguity.

Apply lightness, liberally

Conceptual inversions turned material are helpful for probing, building, and sharing collective thinking and practice around sustainable and equitable computing. Now consider the possibility of collective dreaming. Let’s suppose we identify capitalism, authoritarianism, consumerism, and other -isms as the systems that stand in our way, but the tools we have to hack away at them are largely created by and through those systems. What we have is the ability to practice collective dreaming, and rehearsing the rituals that nurture optimism in relation to those dreamings. Can we dream up scenarios and parallel worlds in stories, music, dance, and games?

We cannot take things or people with us that we encounter in our dreams. But our baggage may include the songs, gestures, and daily rituals we experience there. In our actual lives, we can practice accessing that feeling of lightness that dreaming affords. Our horizons might be clouded by smog and toxic fumes, but our collective internal compass can remain calibrated. Can we imagine radical futures without sentimental nostalgia for pre-technological days?

This next, and for now final, prompt is borrowed from Matthew Fuller’s Media Ecologies.

- Prompt: "Accumulate information, techniques, spread them about, stay with a situation long enough to understand its permutations. Find a conjunction of forces, behaviors, technologies, information systems, stretch it, make it open up and swell so that each of the means by which it senses and acts in the world become a landscape that can be explored and built in. Speed it up and slow it down so that its characteristic movements can be recognized at a glance. Lead it through a hall of mirrors until it loses a sense of its own proper border, begins to leak or creates a new zone."[17]

5. [Root form of verb + adjective]

- Prompt:

6. [Root form of verb + adjective]

- Prompt:

7. [Root form of verb + adjective]

- Prompt:

...