Workshop Matters and Materials

Anja Groten: Gabriel you and H&D are frequent collaborators. For instance you initiated Multiform—a non-competitive queer sports game during the H&D summer academy in 2019.[1] In this game, players are invited to change teams during the games through transformable sport uniforms. By allowing people to perform fluid identities, the game opens up space for experimentation, play, and collective reflection that challenge fixed categories.

Gabriel Fontana: Exactly. Our collaboration unfolded around my research on how ideologies shape movements and vice versa. In particular, looking at how our bodies constantly propagate, internalize, and reproduce social norms.

AG: And there were a few other occasions our exchange continued. For instance, together with Vivien Tauchmann, you hosted a workshop about mobility and public space at the Design Department of the Sandberg Instituut where I work as an educator, and last year you hosted a channeling listening session on the last day of the H&D summer academy. [2] The last time we talked was on the occasion of a workshop I hosted, which was addressing the workshops as such. One of the sessions was dealing with what I came to refer to as a “pedagogical document,” which is a kind of genre of graphic design, but also a genre of design pedagogy and collective practice. Pedagogical documents could be instruction manuals, how-tos, scores, workshop scripts, game plays. These are documents to learn from and with. They are documentation of ephemeral learning moments but also cater to future use. You read my invitation to this workshop and kindly offered to send me your repository of pedagogical documents. I was very curious about them and more specifically about how they relate to your practice?

GF: Indeed, workshop manuals are at the core of my pedagogical practice. Year after year, I developed a collection of scripts that I designed for workshops and classes, facilitated in various contexts such as Sandberg Instituut; BAK, basis voor actuele kunst; and Design Academy Eindhoven.

AG: What is interesting to me is that these documents are not recipes or instructions for best workshop practices. They are highly contextual. So I thought it would be interesting to meet and go through our personal collections of these ephemeral scripts and how-tos, and perhaps talk about our shared fascination for them.

GF: I started to develop a workshop-based practice during my studies at the Design Academy Eindhoven. First, I was mainly facilitating short-term workshops related to my research on sport, physical education, and queer pedagogies. These workshops were not required to be printed as a script. At times, the script was directly embedded in sport tools I designed such as the transformable uniforms or alternative sport fields. After that I began to extend my pedagogical practice to other topics and formats, which required me to find other structural tools such as workshop manuals.

AG: Did you make the documents you brought?

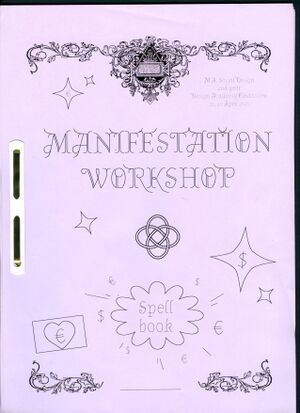

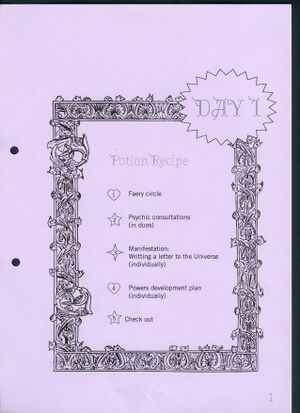

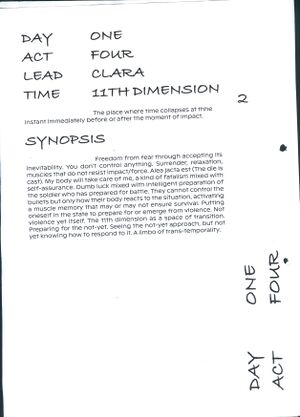

GF: Yes, I have been making these for the past four years. Let’s start with the manual I made for the Manifestation workshop that I have been running at the Design Academy Eindhoven since 2021. It was a professionalization workshop that invited master’s students to play with manifestation techniques, astrology, and the vocabulary of psychics as tools to explore the potential of their postgraduate journey. What I find interesting with this manual is that it is not a dead object but a document that integrates participants' feedback and keeps on evolvingand being updated year after year, workshop after workshop. Designed as a spell book, this manual provides incantations, recipes, instructions, tarot reading, and diverse resources. Therefore, it does not only offer practical information but also helps to set a specific narrative for the workshop.

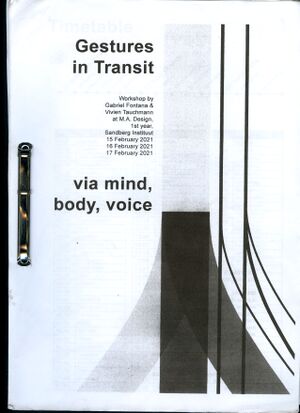

AG: lt is an incredibly elaborate document. It reminds me of this other one you made with Vivien for the Gestures in Transit workshop, which I have here in my document pile.

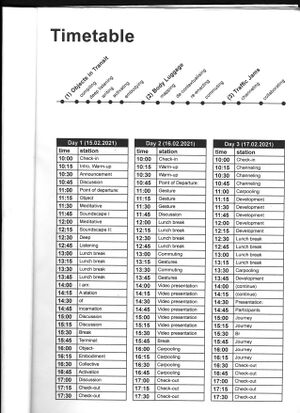

GF: This workshop was looking at how the design of public transport shapes our freedom of movement. Therefore the aesthetic and structure of this manual is very different from the one I made for the Manifestation workshop. When I develop and structure a workshop I consider how to use both the visual codes and language related to the topic. For instance, for the Gestures in Transit manual, we literally used the layout of the train schedules to structure the workshop, which, as is public transport, was really strict in timing.

AG: Its function is to create a shared experience, a world within which the workshop takes place.

GF: Definitely. And it can also create excitement among participants. I always love the reaction when I bring the pile of manuals to the group. This makes them excited about the workshop and they see the value in it.

AG: It is a beautiful gift you bring and also shows a commitment towards the time you share with the group of participants.

GF: Yes, and for me taking the time to prepare and design the workshop manual is also an exercise of care, in a way. It helps me to put myself in the participants’ shoes to imagine how they might receive and understand certain instructions. In this way, it also helps me to imagine myself within the space.

AG: Such a document is a flexible information source and structures the workshop. Individual participants, if they feel the need, can gain more structure, or just let go of the document and go with the flow.

GF: It offers them a timeline and a clear understanding of where we’re headed. In addition to this, I also see the manual as a script to activate the group. When we come together in my workshops, we always start first by reading out loud the synopsis of the day. This small text introduces the main themes that we will explore. Once everyone has entered the room and I feel that the group is ready, I just start reading it so people understand that the workshop is starting without me having to announce it.

AG: Like a ritual! At some point they will also know, OK, he's picking up the manual. It's going to start again.

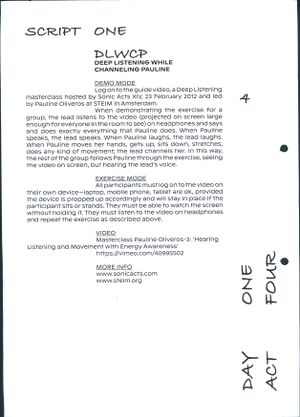

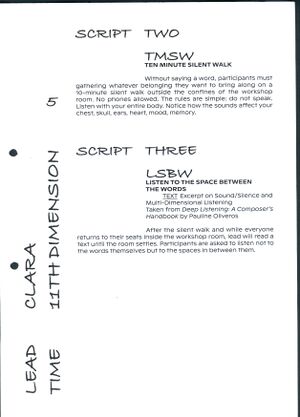

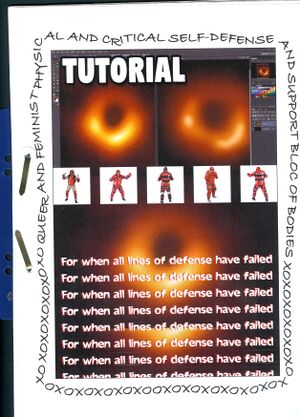

GF: I also brought another workshop manual that we designed with Clara Balaguer and Sarafina Pauline Bonita for the QFPCSSBBXOXO (Queer and Feminist Physical and Critical Self-Defense and Support Bloc of Bodies) workshop we facilitated together at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, in 2019. This five-day training explored different techniques for channeling voices as a tool to deeply listen, share, and heal traumatic experiences related to patriarchal violence.

AG: I remember that you introduced some of these channeling techniques during your last performance and workshop at H&D summer academy in 2021. Could you tell more about how the method of channeling relates to the topic of self defense?

GF: In the case of this workshop, we were talking about trauma and violence, and asking how one could inhabit the retelling of experiences of violence in a way that is less violent, that does not re-traumatize. As a speaker of uncomfortable things, when you’re hearing, seeing, or otherwise sensing audience feedback, it can be difficult to hold your thoughts in the way that you want to hold them and express them with resolve. When you’re picking up on audience reactions—even empathic responses can be distracting—this distorts or amplifies what you are feeling, making it laborious to continue. In this context, it was important for us to develop tools that allow us to share personal and difficult stories with an audience without being directly confronted with them. This gave way to the technique of channeling, a tool that allows you to talk through the body and voice of someone else and therefore to communicate with an audience without having to be present in the room.

AG: I feel like through these kinds of methods, workshop knowledge travels through many spaces and contexts. But at the same time they are so specific and contextual. The story you are telling me about the motivations behind channeling seems significant to the method and to the workshop topic and experience.

AG: This document here, its a method for feedback by a performance scholar Liz Lerman. It is called the “Critical Response Process”—Actually, I think there is copyright on it. But there is quite some documentation of the method online—which I have started using in my classes. I tried some of these methods with my students and reflected on the method with them. I found there was a bit of resistance towards being directed and guided by strict methods, perhaps this is particular to the environment of art and design, education, and these self-organized learning spaces we are both engaging with. We don’t want anybody to tell us what to do! But if there is some kind of mediation as well as a certain malleability to the script, and attention to different modes of interpretation of these exercises, maybe rewriting them together can be quite a fruitful learning instrument. Learning experiences in practical education like art and design can sometimes be latent and not so explicit because it's not necessarily articulated. A pedagogical document and a certain commitment to it can make the implicit explicit somehow. It can turn a situation of doing things together into a critical and conscious learning experience. That is, not by itself but rather through its activation. I wonder what ways that such workshop scripts could be disseminated in response-able ways, with attention to their iterative potential, their histories, and future use. It's not necessarily about authorship or crediting, but about how and why these methods were activated and in which context. To me, it is so interesting to hear how you relate to channeling as a method, and it makes apparent that it is a method that cannot just be applied to any context, like you’d “execute” a script or “run” an algorithm.

AG: Look, this script has been with me since 2010.

GF: Wow, and it's still alive.

AG: It's a workshop prompt by the design collective Åbäke. I've used this method several times before. I usually explain where it came from and why it was useful to me. It's a small gesture. Åbäke came as guest tutors to host a workshop at the design department of the Sandberg Instituut, where I studied between 2009 and 2011. They made us hijack each other's research projects for two days. That was it! The education at the time was rather focused on individual research trajectories. Every student was supposed to have their own research project that you work on for the duration of the two years. The way the course was structured was building on students self-organizing and working in a self-directed way. For me this approach was actually rather challenging. I was quite lost and I found it really hard to push my own agenda... because I'm very receptive to my environment, and I like to do things together. It was such a relief that I could just hand over my project to someone else and get someone else's project for two days. This small intermission gave us permission to step out for a moment. It really influenced a lot of people's trajectories. And I've used this method many times since.

The Åbäke script is an interesting design object. These documents, workshop manuals, and how-tos also, in a way, have their own kind of graphic design rules. On the one hand they are well taken care of: they are concise and easy to reproduce with regular office supplies, which makes them also easy to rework, annotate, and appropriate.

GF: That reminds me, usually I share these manuals not as a .PDF but as a scan of the printed object, so you can see the color of the paper as well, and workshop participants really receive it as an object. AG: Interesting, I too have thought about tricks to better contextualize these documents and their moments of activation, their liveliness, and the different transformations they go through. For instance, I made videos in which I tell the stories of the documents while holding them in my hand, sifting through them, so you see them being touched and activated. In our last H&D publication, Network Imaginaries, we published workshop scripts but we did this in a way that all the scripts became uniform. In retrospect I think this flattened them, and we lost their moment of activation and the memory of them as well.

GF: I think I was not so aware of why I was scanning them. But indeed the materiality and reproduction tells us a lot about how to understand such an object, and how to relate to it.

AG: And yet, I think the facilitator—and their sensitivity in activating these manuals—seems crucial for such a document to be purposeful.

GF: Definitely.

AG: There have been times when I thought I had come up with the most amazing workshop and then when I ended up in the space, and while trying to activate it, I realized, oh, I've assumed a lot here. For instance, a common knowledge, or that I’ve assumed there is a sort of common ground in a group from the start, perhaps a shared interest, solidarity. But sometimes through giving workshops, especially because they are temporary and very quick, you end up rushing through those assumptions.

Within your practice–and I relate to this as well to some extent–there seems no separation between being an educator and being a designer. These workshops you are hosting, while they may be short encounters, are never really just a one off thing because you build a kind of body of work around them, they are all connected in a way.

GF: That’s why documentation is such an important question. For example, it was difficult for us to document the queer, feminist self-defense workshop, so the manual became the documentation object of documentation.

AG: This really resonates with me. Often I don’t do anything with the outcome of a workshop I facilitated. These so-called outcomes don’t seem to be meaningful outside of the context they were produced. It produces a certain result, or something to work towards, which seems to be necessary in the moment for a process to take place, but not as a means to an end. And therefore these materializations, sketches, and prototypes, are perhaps not for everyone's eyes. I'm always questioning what ways to document and disseminate this kind of ephemeral workshop practice. I do think from the way you explain your considerations and experiences, that it is important to understand the context, who was involved, how, and where these scripts were really activated.

GF: I taught for the past three years at Willem De Kooning Academy in Rotterdam. There you are asked to bring your own personal practice into the development of the curriculum. However sometimes the curriculum and exercise instructions you develop get passed on to another teacher. I feel some tension here. On the one hand, I believe in open-source education, but on the other hand the knowledge and tools that you bring to the class always come from a specific context and are therefore always situated. Maybe we need to start designing manuals about how to disseminate our workshop manuals.

AG: In a way, this publication is an attempt to think about other ways of disseminating such documents. It's not just about sharing these scripts as they are, but taking specific pedagogical documents as a starting point for engaging in conversation. Maybe we will be showing bits and pieces of the documents, show them in action, perhaps, narrated, iterated, annotated, discussed, in order to situate them a bit more. I have been experimenting with the idea of facilitating a workshop where there is no facilitator, where it kind of runs itself. People get into groups and they get this kit where they have to follow the prompts and make sense of the workshop together. There's definitely a limitation to this approach, but it's an interesting exercise to thoroughly script a workshop in such a detailed way because you create documentation already and have to imagine the situation much more vividly.

GF: It's also interesting to see at the end how people interpreted the instructions. Another thing that I always try in my workshops is to demonstrate as much as possible. For example, when I facilitated the channeling workshop at H&D summer academy in 2021, I started with a performance that demonstrated the channeling technique. The participants at first didn’t really understand if this was just a “normal” conversation between two people or a performance following a specific script. It was only once the performance was over that the script and the channeling technique were revealed, which then became material for participants to play and experiment with.

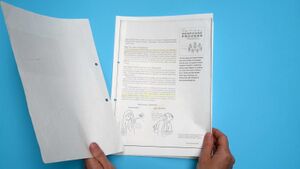

AG: This one is also an interesting script. It is an example of how the layout of a specific document can afford a particular interaction with it.

GF: There is a lot of space.

AG: Indeed. You can imagine yourself just scribbling on it, working with it. Sometimes when these scripts are too beautiful they don’t afford that.

AG: This document is actually the script of the workshop that I invited you to, and which started this conversation. The scripts exists and was activated in several iterations. In this particular iteration I asked friend and performance artist, Pia Louwerens, to host my workshop. She also works with scripts in her practice. Somehow, she could connect all the points I was addressing in the script to her own experiences. She had her own ideas about it, so she kept the original script intact, but copied it, leaving plenty of space on the left and right. Then she annotated it for herself, and hosted the workshop. I was there as a participant. She followed the timeline of the script but then, for instance, for the introduction, she gave her personal introduction to the workshop, and explained how it relates to her practice as an artist working with institutional critique, arguing that scripts are always already present. In her work, she works with hidden scripts (literally or figuratively) of institutions—constantly negotiated and questioning what is expected of an artists by an art institution and vice versa—and then she was hired by me to give this workshop, which presented yet another script to negotiate with. In this workshop, she somehow managed to reflect on all of these different layers of the scripts-in-action. It was quite mind-twisting to participate in my own workshop, but also incredibly insightful.

GF: I guess it’s a nice way to get some perspective.

AG: Yes, exactly. And also it created a kind of discourse around this kind of pedagogical aspect of people’s practices.

GF: I love this collection of manuals you have.

AG: I'm working on a kind of bibliography of these documents for this publication, to republish them, in a situated way, and emphasizing the stories they are connected to.

GF: Clara and I have this thing going on, where we swing new manuals to each other. We should really bring them together once and do something with them!

AG: Let me know! I want to be part of that meeting!

Gabriel Fontana is a social designer. He is the initiator of Multiform, a tool that challenges and examines ideas of identity, community, and inclusion by proposing games for sport classes at schools, generating an openness and empathy that later on filter into wider society. Through a queer framework, Fontana investigates how daily social practices reproduce conservative values and reinforce power structures. Within a phenomenological approach, he develops performative design research, positioning the body as the central perspective from which the social world is experienced, reproduced, and challenged. Fontana lives and works in Rotterdam.