Across Distance and Difference

Proposition

To create a design framework and method for carrying out self-initiated projects and research processes collaboratively and passing them on as a set of instructions or rules:

#1 The commitment: Decide to carry out a joint project.

#2 The project: What do you want to work on? What have you always wanted to try out? What do you feel like doing?

- Develop a sense of what your collaboration could be about and decide on which interests you would like to combine. It is not about reaching an agreement but rather about individual interests coming together on a joint project.

#3 The format: How do you want to proceed? Create time and space for the project by deciding on a format. It may help to build on and modify existing formats.

- Examples: Start a club, conduct workshops, invent a ritual, establish a pen pal relationship, start a diary, create break dates, etc.

#4 Short reality check: Not all participants will have the same needs, capacities, and resources. Keep this in mind and integrate that awareness across all parts of your project.

- What are the different capacities, conditions, abilities, or obstacles that shape your project? Do you have different family commitments? What are your work contexts? What are your daily rhythms? What do you wish for in a collaboration?

#5 The rules: Draft a clear framework taking different variables into consideration:

- Time: How long should the project last? When and how often should you work on it?

- Is there a certain rhythm, e.g., once a week/day? Are there certain times, e.g., in the evening, or certain moments, e.g., when you need a break from other commitments?

- Space: Are there meetings? Where do they take place?

- Do you meet in your private rooms, outside, in a café, at your workplace, over the phone, or on a video call?

- Tasks: Define specific actions, parts, or steps to follow and create space to adapt the format individually as and when needed.

- Consider the different capacities and needs of the participants again. Integrate a safety net and think about how your project could be harmonious and feasible even if you have to deviate from the rules.

#6 Reflection: Take time during and after the project to record your thoughts and experiences and discuss them with each other. The reflection can also be used to adjust your format.

#7 The proposition: Write down the individual steps you took in the project.

- How did you approach the project and what were your ways of working? What decisions were important? What would you like to pass on?

- Formulate these as propositions for action in different steps, rules, or formats.

The Asynchronous Remote Reading Club

A framework for taking the time to read, discuss and share literature references with another person.

Prompt

- We agree that each person will find a time slot to read something every day. We will check-in on our personal needs and decide whether to read or not. Unlike a usual book club, we don’t have to read the same books or texts. It is up to us whether we want to focus on one book/text, create a reading list with different books/texts, or decide spontaneously what to read on the day.

Sharing

- We agree to send a voice message to each other every day.

It's up to us to decide what we talk about. We can share thoughts about the book/text or talk about our day.

Variation

- Instead of limiting the format to books, you can also include museum visits, lectures, or workshops.

- For a one-person club, voice messages can also be replaced by journal writing.

Piled up books and messages

The one-week-experiment, The Asynchronous Remote Reading Club, evolved from the shared feeling that we rarely find time to do personally meaningful things, especially activities such as reading. We both love books, but since we started new jobs—Hanna as an in-house graphic designer at a museum and Mio as a freelance designer and educator—we often lack the focus or energy to engage with the books that have been piling up next to our beds and in our living rooms. To consciously make space for reading, we came up with the Asynchronous Remote Reading Club—a simple framework that had a trial run for one week in August 2020. Besides reactivating one of our passions, the experiment was aimed at sharing something together while being physically far apart. We’ve always lived in different cities, but since graduating from Karlsruhe University of Art and Design, we no longer see each other at school and have moved to cities further away than before, which resulted in us slowly losing contact. Therefore, the project was also about reconnecting and finding other ways to spend parts of our daily lives together.

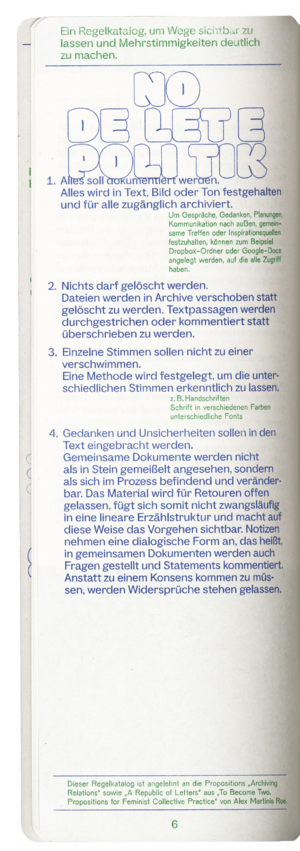

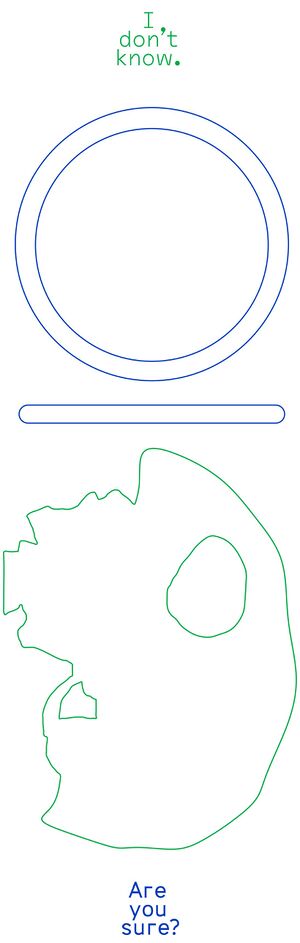

- The process of creating formats for specific kind of collaborations calls to mind a project we conducted in 2019. “I don’t know. Are you sure?” searched for ways of working together that actively engaged with friction as well as appreciating differences over seeking compromise. The collection of fifteen collaborative methods alongside short conversations can be downloaded via bit.ly/idk-ays. An English excerpt has been published with the title “E for Embracing Differences,” in Glossary of Undisciplined Design (United Kingdom: Spector Books, 2021)

Hanna Müller: We decided that we weren’t going to be dogmatic about our framework and that it would be OK if we couldn't find the time to read each day. We wanted to ensure that the project wouldn't turn into another item on our “to-do” list, and to be aware of our capacities and other responsibilities. How did that work out for you?

Mio Kojima: It worked really well to keep this part of the framework open, and to be flexible about how much we’d read or whether we’d stick to one book or jump from one to another. I decided to make a reading list and engage with a different book every day. Some I had started reading already a year or two ago! The project helped me to rekindle my interest in some of these books again. Additionally, planning my reading sessions as a pause from my work felt good as I often skip breaks or eat meals in front of my computer. That said, it's also essential to mention that I am self-employed and the last week has been very quiet, so I probably had more capacity and flexibility than you, right?

HM: Yes, a lot was going on that week, and I was exhausted in the evenings. Sometimes I felt the build up of pressure during the day, knowing that I had to pick up my book and tick that box before I could completely relax. The other part of our experiment was sending voice messages back and forth to share what we had read, how we made space for our experiment, or whether we had found time for reading at all. In contrast to the reading part, I was pretty surprised by how easy that felt. It helped to have a concrete framework and something specific to talk about. Usually, I don't enjoy communicating extensively via Messenger or on the phone, but now that I live in a different city to many of my friends, I depend on these means of communication.

MK: I relate to that feeling! In addition to sending voice messages to friends, I also communicate via digital means for work. Sometimes it makes me feel detached, and I am currently looking for ways to balance that more. Have you found other ways to connect across this distance?

HM: It varies a lot and depends on the other person. The nice thing about messaging is that you can also communicate through images but this still lacks the depth of interaction I long for. Every now and then I send a postcard or make a phone call, which works well with some friends; when we see each other we just pick up where we left off. Other relationships have become more complicated due to the distance, or have broken down altogether because our needs were too different. How has it been with you?

MK: During the second lockdown, in autumn 2021, I met regularly over Zoom with a friend to talk about what was on our minds. Often, it was related to our work and study situations. Sometimes we exchanged resources on specific topics, such as imposter syndrome, or concrete productivity methods like time management. Some meetings were more experimental and took shape across different formats. It was incredible how much depth our meetings went into, and how we little talked about our personal lives. Our experiment reminded me of that.

HM: How do you feel our experiment connected us?

MK: We shared something that went beyond language; parts of our everyday lives became completely intertwined. I, for example, listened to your voice note every morning while I drank my coffee. It wasn't a conscious decision to do so but it became some sort of morning ritual where you—your voice and your daily recounts—accompanied me through my own days. And because you always recorded your messages at night, I felt I was with you for a part of your evening. It felt really wonderful to connect across these different situations, times, and spaces. How was it for you?

HM: Your messages usually came at noon, while I was at work. I wanted to create time for them consciously, so I usually waited until the evening or the next morning when I had peace and focus to listen properly. It was way more relaxing than receiving the regular messages that I receive throughout my day, to which I often forget to reply. Additionally, it was great to know that I didn't necessarily have to pick up on things you had sent. I could instead use it more like a diary and stay within my experiences and reflections and also take in your thoughts without the pressure to respond to them. In general, I sensed that even though we hadn't seen each other in a long time, we had a solid foundation to build on. Did you feel the same way? If so, how did that become apparent to you? If not, where would you have liked it to be?

MK: When I listened to your voicemails, I imagined you sitting in your living room on one of your big sofas and looking out the window at the beautiful view of your garden. Maybe one of your cats was sitting on your lap and you would pet them while leaving your message. It activated a lot of memories for me, and it certainly made me feel close to you. However, looking back at another voicemail experiment I did half a year ago, I think it is this particular way of using technology that creates that sense of closeness. This diary-like format that you mentioned does a lot. For me, the foundation we built was most evident in the moments where we brought our ideas and thoughts together, in planning the project and in reflecting on our experiences. We know each other well in these contexts, and I think we were able to look out for each other and create a framework that would facilitate our different approaches and ideas.

HM: That's how I perceived it, too! And this intimacy resurfaced more quickly than I expected—the sense of trust and understanding that we can rely on each other. It is the feeling of having a common direction, of the other's presence in our lives even when we don't see each other in person or speak directly.

- This conversation took place on August 10th 2022, the last day of the Asynchronous Remote Reading Club experiment. We met in an online document, both sitting in front of our computers in our living rooms in Berlin and Aschaffenburg. We could neither see nor hear each other but experienced the other’s presence through the characters that appeared one by one on the white digital sheet. We took turns to reply, taking the time to think and formulate, hesitate, and correct ourselves. We experienced the other’s thoughts taking on a life of their own as they materialized on the page before us.

Mio Kojima (she/her) is a German-Japanese designer, educator, and researcher. Her passion lies in playful and collaborative approaches to creating and sharing knowledge. Since 2021, Mio has been the managing editor of the queer intersectional feminist platform Futuress.org, and she has worked as an artistic associate at the artists-run initiative and a residency program AIR Berlin Alexanderplatz since 2022. She works as a mentor at Make Your School, teaching teenagers how to code and critically examine their school environment.

Hanna Müller (she/her) is a communication designer with many interests. She loves to think about political and social issues and how they can be represented through different media. Hanna likes to work with images, voices, moods, and colors. Currently, she holds a position in exhibition design at a small museum near Darmstadt.