Scoring

scoring

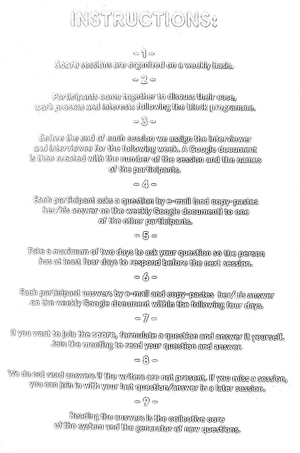

Our score practice consists of weekly encounters with a group of artistic researchers. It frames the time and space for task-oriented encounters on a regular basis, as a form of conversation and exchange. These meetings are based on a Q-and-A structure that entails material practices and the formulation of questions.

- Each participant in the score practice presents, in the first meeting, their work in a chosen medium for five minutes.

- A procedure of changing roles assigns a person to formulate reflections and questions to another person: by chance operation, it’s assigned who formulates reflections and questions to whom.

- Reflections and questions are shared by the participants by email with a delay of two days.

- The responses are presented in five-minute presentations the week after.

- The full process is repeated weekly for a period of three months.

The focal point of using scores (i.e., sets of instructions like the one above) as a pedagogical tool is to bring together a plurality of practices in conversation, without determining the languages these practices are ‘talking’—movement, words, text, somatic approaches, film, design, activism, theory. The participants of the score contribute to each session with materials that engage their concepts, forms, and contents as performative contributions to collective learning. The [often unexpected] subjective positions emerging from these encounters are produced by the way proposals are materialized, addressed, and situated.

Who’s talking through them, who are they talking to, and what kind of entanglements are they proposing?

The score can be seen as a generative infrastructure that invites to participate as fellow researchers in each other’s practice. It is a form of engaged spectatorship based on responsiveness and response-ability (K. Barad) which allows to think through the relations and attachments suggested in each participant’s proposal.

and reposition oneself as part of world(s).

In trying to deal with questions related to co-learning that aim to encompass dissensus, not knowing, methodological understanding, authorship, politics, backgrounds, histories, criticality, sociability, institutional framework, philosophy, ecologies, and material practice (a lot!), the scores can enable a platform for exchange through critical making.

What we can learn from engaging with each other in such a way, is that form and content are always already symptomatic of a set of relations, and that these sets of relations propose degrees of inclusiveness, contradictions, and resistance.

These encounters propose a form of sociability, by their regular character over a period of time, but most of all by virtue of the subjectivities that emerge out of them. The type of engagement at stake is one that I can name as friendship (see artificial friendship): curiosity, presence, offering of time, attention, staying with, consideration, but also dissensus, opposition

and criticality as a form of care.

The question these scores address and that I’m eager to expand and discuss would be how to develop infrastructures that frame, without polarizing or stigmatizing, knowledge production; how to think infrastructures of encounter that propose ways of ‘reading’ and ‘writing’, ‘re-reading’ and ‘re-writing’ through each other’s practice, as a methodology for understanding and crafting differences that matter outside of specialization or a discipline. What kinds of institutional support structures can be developed to sustain and empower the transformation and re-actualization of the values attached to artistic practice, and how to value them as matters of concern? (Bruno Latour)

The eternal quest for understanding, and the eternal impossibility of achieving it, leaves us with the wonderful possibility to experience/experiment with complexities.