Am I a hacker now?

Solarpunks Intergenerational Workshops—Amsterdam edition

"Am I a hacker how?"

Quote by Uma (11-year old participant)

As part of an international collaboration on the topic of solarpunk, H&D members Loes Bogers, Pernilla Manjula Philip, Anja Groten, and Heerko van der Kooij developed an intergenerational workshop for children and adults that imagines sustainable networking in a solarpunk manner. In this text we reflect on the workshop experiences and how they helped us to articulate our views on what solarpunk could mean within our practice.

Solarpunk beginnings

The term solarpunk was not invented by us. Solarpunk is an existing movement, aesthetic, and genre of fiction—including literature but also art, fashion and activism—that envisions a future where inhabitants of the earth have managed to find a way to live sustainably, and/or imagines how we might get there. Jay Springet compiled a nice list of references.[1] What you notice in these texts, and the imagery associated with it, is that technology plays a role in supporting the lives of people as well as other living beings. H&D approached the concept in a very hands-on way: by carrying out practical experiments around an alternative internet— network infrastructures—that are more sustainable than our current infrastructures and the way we design and use them. Exploring no-power or low-power computing can be solarpunk, for example. Solarpunk has radical potential, it's optimistic and hopeful. For that reason it seems like a fitting genre to explore with children. Children are quite good at imagining things in a positive way and are often unafraid to tear things down. This seems fitting to the project of radical future-making: things cannot stay as they are, something's gotta give.

Examples of solarpunk that resonate with us are the works of fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin, in particular the novel The Dispossessed (1974). The role of technology in this novel is very advanced (like quantum technologies advanced), but limited to the common good—never solely for the benefit of one (group of) individual(s). It also portrays queerness and forms of childrearing, and alternative divisions of labour, which particularly resonated with us in the context of this intergenerational project.

The afro-futurist blockbuster Black Panther (2018) could also be seen as an example of solarpunk. It shows a way of dealing with technology in a society that is highly advanced and at the same time attuned to prevailing living eco-systems and natural resources.

In our shared solar punk adventure we tried to build something that could be anchored in a concrete setting within which fictional solar punk scenarios could be experience in material ways.

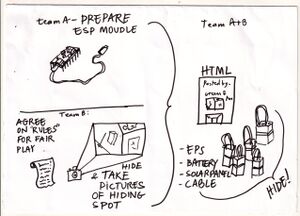

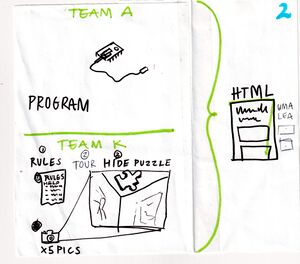

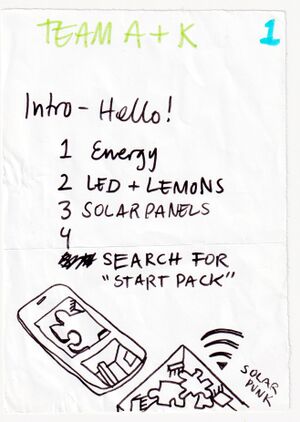

Scavenger Hunt (Bring Your Own Grown-up)

We developed the workshop Solarpunk Kids Scavenger Hunt (Bring Your Own Grown-up), which was held at NDSM-Kunststad in Amsterdam, and later at Page Not Found in the Hague. For this workshop we invited the participating kids to bring a grown-up they liked. In most cases—but not all— this was a parent. In the workshop, participants learnt how to program solar-powered wifi modules and played a digital scavenger hunt in public space together. To create this, we proposed that the kids would play the role of the game “designers” and the parents would play the “hackers” of the infrastructure.

- “Turn on the wifi on your phone and see if you can find the network called ‘solarpunk-schat.’ What happens when you connect to it?”

- “I see a website that says we have to look for a treasure that is hidden in the NDSM hangar

- “I think I've seen those yellow pillars shown in the photo! Come!”

- “Oh I can't see the website anymore, the signal is gone, did anyone save the pictures?”

- “No, let's go back to the signal and look at them again!”

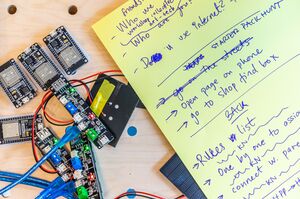

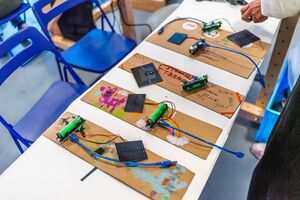

In the workshop, the hackers (grown-ups) learned how to program an ESP-based device so that it functioned as a small local web server which could host a small website of no more than 1 MB. The device can be powered by a battery that is charged by a small solar cell, which serves as a mobile signal sender that broadcasts the website locally—not via the WWW—from your pocket or wherever you put it in the space. Each server gives out a Wi-Fi signal with a range of 20-25 meters, so users have to be pretty close to the module in order to connect to the wifi signal, and see the small webpage the ESP is serving. While you are connected to the ESPs wifi signal, you can view the page that holds the clues you need to find the hidden treasure. We were first introduced to this method by dianaband, an artist-duo based in Seoul who used it in the Walking Signals workshop they hosted at H&D in 2019.

- “I found the box!”

- “Great! What's inside?”

- “Umm, a lot of little devices, I don't know what they are, and pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.”

- “You found the workshop materials! With these, we will make a small, solar-powered internet, and design a scavenger hunt game for it that we play together at the end of the afternoon.”

- “Oh cool, do we each get one?”

- “Yes, each of you gets to hide one piece of the puzzle, and you will make a website together to provide clues about your hiding spots.”

- “But first, let's talk a bit about the Internet. Who is willing to share how long you are up before you open your phone in the morning?”

By means of introduction, and to activate the knowledge and experiences already present in the group, we asked questions such as: Can you name any devices the Internet is made up of? Do you have an idea what a router does (that little device with the lights, that is probably in your hallway or in a closet)? Where does a website live? Let's compare our mini servers to a "data center," how is it different you think? How much power do these consume? Is it bad for the environment?

The small DIY internet we made in the workshop helped to put into perspective the scale and vastness of the resources, materials, and infrastructure to be mined, dug, and maintained in order to create the Internet as we know it. The system was not going to be worldwide, more of a neighborhood network. What would that mean and what would it allow us to do? Is it possible to imagine that not all of the Internet has to be worldwide and running all the time? How much power is consumed by everyday infinite scrolling and streaming? Is it bad for the environment? What could a lighter, more sustainable internet look like? And would such an internet be as fun as the one we know?

- “Can you think of a moment when you noticed that the Internet is very ‘heavy’?”

- “Yes, when a YouTube video loads very slowly and keeps stopping!”

- “Ah right, yes, I get that too sometimes. What can you do to make it better?”

- “Well, you can change the quality but then it looks a bit ugly and it's not as fun.”

- “Sure, if you don't have the bandwidth for it, it's not so nice to watch a heavy video. What could we do to make it lighter?”

- “Umm maybe we could make all the videos extra fast, so they're shorter? That could be funny.”

- “Good idea! Maybe we can think of some more ways to make a smaller internet, and make sure it's still really fun.”

The Internet often feels like an abstract thing for most of us, even though it's everywhere, all the time. But building a kind of internet for ourselves allows us to relate to networking in a new way. It becomes less abstract and more of a material to work with/against/through, which continuously interacts with all sorts of other things. In the process of doing that, you notice that not everything is possible and there are many forces with which to negotiate. People might police the space you are working in, and ask why you are installing strange devices. There is limited memory space available on devices you can power with a solar cell, so you have to shrink your ideas somehow. There are other people who might be younger, or older, or otherwise different, so you have to adapt how you play to make sure everyone enjoys themselves and feels safe.

- “So, designers, let's decide what our rules are so everyone has a good time. The grown-ups also have to follow them, so this is your chance.”

- “Don't hide anything higher than your head so everyone can reach it!”

- “Be nice and help each other!”

- “The grown-ups have to get us ice creams!”

- “Very good. We're ready to go hide the puzzle pieces! Make sure to pick locations that are challenging but not impossible to find. Take a few photos of where you hid the treasure.

These photos will serve as clues for the other designer/hacker duos. No snitching about your hiding spot!”

The treasure for this scavenger hunt was a jigsaw puzzle, but it could be anything. The first time we played the game were at NDSM Kunststad, where the H&D studio is based. NDSM was previously a ship wharf and now hosts studios for all kinds of creative people, as well as hosting regular events like a large flea market. It’s a very large space with lots of little nooks and split levels. The location plays a huge part in establishing the dynamics of making and playing the game. A good way to start is to go out and observe the surrounding area such as streets, people, shops, and sounds. Sharing ideas and thoughts in a space with people you have just met can be challenging. We found that physical activities such as exploring the area were a good way to break through these initial discomforts.

The second workshop was hosted at the bookshop Page Not Found in the Hague. This time, the space wasn't big enough for the scavenger hunt, so we had to take it outside. And sure enough, it was raining all day. As such, part of the design process involved approaching shop owners in the neighborhood and asking them to hide our treasures and host our electronics inside their shops. Our requests were met with curiosity and enthusiasm. Some of the shopkeepers even logged into our internet with their phones, kept up with the workshop as it unfolded and found out where the clues were hidden. With these new (passive) participants, putting up our temporary light internet involved more actors and negotiation. Hosting a workshop on the streets and making contact with shopkeepers relates to the real-life Internet: Where do you put the infrastructural elements? Whose cooperation do you need? Who gets to say yes to a datacenter and what does it mean for the place where it’s built?

“Now that all of you have hidden the treasure and taken pictures of the hiding spots, let's think of clues to help the other players find your treasure. Are there interesting details that could help the players to recognize the spot? Which details do you want to give so players know where to look without making it too easy?”

We asked the designers to provide clues in the form of text and images to help the players find the treasure during the scavenger hunt. They explained this to their hacker partner, who by this point had learned how to upload a 1MB website to the Wi-Fi device. After pairing up again and showing each other what they had done so far, each pair was asked to create a very small website that provided the clues, and upload it to a server module. In the process, the designers shared tricks and tools for dithering and compressing images, finding cool fonts, and downloading GIFs from a website.

- “How big is 1 Megabyte?”

- “Hmmm, I don't know. Not very big?”

- “I think a high quality photo you take with your phone is already more than 1MB?”

- “And videos are even bigger.”

- “That's totally right. One minute of MP3 audio is about one MB, or one good quality picture from a website. These are often made a bit smaller before they are put on the Internet. That's called compression and there's many tools for that.”

What are the limitations of the hardware we chose to build this DIY internet? For one, it meant that the designers could not build websites larger than 1 MB. Because file size is quite an abstract concept, it was interesting to explore how a 1 MB website compared to a website, or an hour of online gaming or YouTubing. How can you make files smaller using compression tools, and how does that relate to file sizes and file types?

- ”Uploading the websites is in process! Let's take a look at the other parts we need. What else is in your kit?”

- ”A solar panel! And a battery I think, and I don't know what this device is.”

- ”Ok let's see how all these things need to be connected, we made some instructions to help you.”

- ”Which one is the minus side of the battery again?”

- ”The flat side!”

- ”The first modules are ready, let's make cardboard houses for protection that keeps it all together. You can also design it and make it look good!”

It was fun for the kids to design small boxes for the models and it buffered some of the time required for website building and hardware uploads. Some kids found this part a bit too tedious, and crafting the housing was a good hands-on alternative. It turned out that these playful box designs not only protected the devices, it also made them look a more innocent, like a friendly disguise. When we were testing the modules during the workshop development process, someone had already come up and asked what we were doing. They had become suspicious having seen two adults leaving random hardware in a shared space.

- “All set! One of the hosts will go and hide your modules now, so it's a surprise for everyone where the network nodes are broadcasting from.”

- “In the meantime, we still have to tell the grown-ups about the rules we made to play the game. Who wants to explain the rules? ”

- “I will do that!”

- “Oh, and I see there's something about ice creams...?”

When all the servers with the clue websites were hidden, we made a list of network names to look for, and played our own adrenaline-fueled scavenger hunt. Participants had to find and connect to Wi-Fi networks on their phones to see the clues for where the treasure was hidden, and continue until the entire puzzle was complete. The workshop culminated in playing the game, which was fun and exciting to play together. And of course, there was ice cream to top it off.

Reflection: Solarpunk futures

The workshop was developed in the context of a larger collaboration with feminist hacklab Mz* Baltazar's Lab in Vienna and feminist makerspace Prototype in Pittsburg, with whom we regularly exchanged ideas and tracked our progress. Our regular conversations helped us grow further understanding of other locations, communities and urgencies, as we developed the intergenerational solarpunk workshops connected to our respective practices. Stefanie Wuschitz from Mz* Balthazar's Lab gave a very insightful presentation about the materials involved in creating the circuitry for the ESPs, batteries, and solar charging boards we were using. It transpired that this electronic circuitry, and the batteries needed to transmit steady voltage to most computer chips, contained many toxic and/or finite resources like semi-precious metals. This discovery set us back slightly: We wanted to make a solar powered internet, but for that, we needed batteries, circuit boards, the solar panel itself, and a microcontroller. So we had to sit with that thought a bit more.

Solarpunk is known for having a positive attitude toward the future, but at the same time it is positioned as an adherent to the systems that prevent this brighter future from being achieved—making it anti-capitalist, anti-authoritarian, anti-consumerist.

These critical reflections led us to zoom in on the general assumption that any problem can be fixed with more technology. Such problem-solving attitudes are preserving the status quo. A positive outlook and creative space can be found in playing and experimenting with expectations and demands that are put on the tools like network technologies. Do we really need constant internet access, and for every single thing we do? Is there a way to do more with less? Can the practice of unlearning or deactivating desires around technology show us new ways of imagining desirable futures?

For us, both the development process and the actual workshops provided critical yet thoroughly joyful opportunities to carve out a playground for sharing, rewriting and acting out techno-imaginaries for our shared future.

Do you want to host your own workshop? The complete workshop script is available here: https://github.com/hackersanddesigners/WifiZineThrowie_ScavengerHunt

Loes Bogers is a jack of all trades, exploring many disciplines at once. She often gets lost in the world of technology and philosophy, but fluidly tinkers her way back with her accessible hands-on approaches to complex ideas. Loes has formal training in interactive media (MA, Goldsmiths) and media theory and cultural studies (BA, University of Amsterdam). She is an experienced facilitator and educator, and sometimes writes when she's not busy dancing or shape-shifting all things tangible. She has been a core member of Hackers & Designers since 2019 and currently works at the Amsterdam University of the Arts. Loes is based in Rotterdam.

Pernilla Manjula Philip is an Amsterdam-based Desi from Sweden who likes to make things and tell stories. She’s interested in exploring what it’s like to live in a body in the world. She wonders how tools shape norms and influence our feelings. How do institutions like the healthcare system affect confidence? Can you build your own tools to help? The artworks Pernilla likes to make often take her lived experience as a starting point, although a variety of experiences and viewpoints are central to the process.