CriticalMaking: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (69 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<span class="author">Florian Cramer</span> | <span class="author">Florian Cramer</span> | ||

On its most simple level, critical | <div class="no-indent">On its most simple level, ''critical making'' is a contraction of ‘making’ and ‘critical thinking’.<ref>Hertz, ‘Two Terms.’</ref> According to its inventor Matt Ratto, critical making ‘signals a desire to theoretically and pragmatically connect two modes of engagement with the world that are often held separate—critical thinking, typically understood as conceptually and linguistically based, and physical ‘making,’ goal-based material work’.<ref>Ratto, ‘Critical Making’, p. 254.</ref> Critical making thus fuses theory and practice, idea and matter; domains that were traditionally separated in Western culture <mark class="c6">(material practice</mark>).</div> | ||

Critical making has a cultural and material affinity to maker culture and simple-to-use digital technologies (such as Open Source software, social media and 3D printing) that are thought to foster <br> | |||

a culture of ‘<mark class="c7">diy</mark> citizenship’.<ref>Ratto and Boler, ''DIY Citizenship''.</ref> In critical making, these technologies are not only used to bridge thinking and making, but also to introduce elements of design education into social sciences at universities. | |||

Critical making knows at least three different definitions and schools: | |||

# critical making developed and practiced in and for social sciences at the University of Toronto by Matt Ratto and his research team; | # critical making developed and practiced in and for social sciences at the University of Toronto by Matt Ratto and his research team; | ||

| Line 13: | Line 14: | ||

# critical making as a design ethos, proposed and practiced among others at the Rhode Island School of Design. | # critical making as a design ethos, proposed and practiced among others at the Rhode Island School of Design. | ||

===critical | <span class="page-break"> </span> | ||

===critical making in social sciences=== | |||

The following is based on information provided by ginger coons, who completed her PhD research in the critical | <div class="no-indent">The following is based on information provided <br> | ||

by ginger coons, who completed her PhD research in the critical making Lab of University of Toronto:</div> | |||

critical | critical making, in this school, is a practical study and research method for students and scholars with no art, design or engineering background to do part<br> | ||

of their classroom study through material experimentation instead of only reading and discussing texts. | |||

Open Source and Internet ‘maker’ technologies dramatically lower the threshold for non-experts to build something—an object, a piece of technology, an application—to serve as a temporary, experimental, and discursive device for studying and exploring a concept or theory. | Open Source and Internet ‘maker’ technologies dramatically lower the threshold for non-experts <br> | ||

to build something—an object, a piece of technology, an application—to serve as a temporary, experimental, and discursive device for studying and exploring a concept or theory. | |||

A cultural studies or feminist theory class, for example, could use critical | A cultural studies or feminist theory class, for example, could use critical making as a classroom method to study and discuss the claim of the African American poet and critic Audre Lorde that ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’,<ref>Lorde, ''The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle'' <br> | ||

''the Master’s House''.</ref> by practically experimenting with the possibilities and limitations of using corporate social media <mark class="c2">platforms</mark> such as YouTube and Instagram <br> | |||

for anti-corporation political activism. | |||

===critical | ===critical making as socially <br>engaged maker culture=== | ||

‘Maker spaces’ became a mainstream phenomenon with the creation of the first ‘Fab[rication] Lab’ at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2001 and the launch of ''Make:'' magazine in 2005 with its network of over two hundred licensed ‘Maker Faire’ conventions in more than forty countries. From the perspective of digital media artists, ‘maker culture’ boiled down to a mainstreaming and commercialization of radical technological | <div class="no-indent">‘Maker spaces’ became a mainstream phenomenon with the creation of the first ‘Fab[rication] Lab’ at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2001 and the launch of ''Make:'' magazine in 2005 with its network of over two hundred licensed ‘Maker Faire’ conventions <br>in more than forty countries. From the perspective of digital media artists, ‘maker culture’ boiled down to <br>a mainstreaming and commercialization of radical technological <mark class="c7">diy</mark> that had existed from Nam June Paik’s self-constructed video synthesizer in the 1960s to, among others, artists’ experiments with self-built radio and tv infrastructures in the 1970s and 1980s, and the ‘tactical media’ movement of the 1990s.</div> | ||

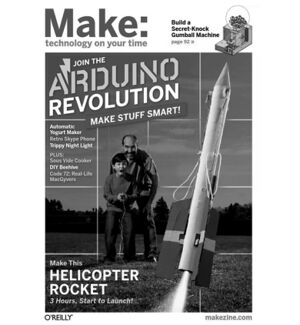

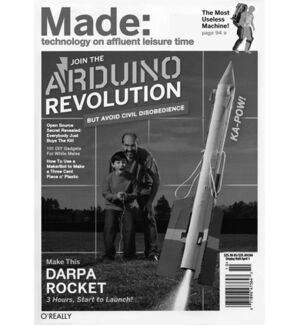

This difference in politics is epitomized by a cover of ''Make'' | This difference in politics is epitomized by a cover of ''Make:'' magazine (vol. 25, 2011) and its parody, ''Made:'' by the designer and artist Garnet Hertz (2012): | ||

<br> | |||

[[File: | [[File:Make_magazine-smaller-adjusted.jpg|thumb|''Make:'' magazine, vol. 25, O'Reilly Publishers, 2011.]] | ||

<span class="page-break"> </span> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

[[File:Made-web-smaller-adjusted.jpg|thumb|''Made:'' (parody of ''Make:'' magazine), Garnet Hertz, 2012.]] | |||

Since Ratto nevertheless brings ‘making’ into university classrooms, it is not surprising that design educators conversely reclaim critical | <span class="page-break"> </span> | ||

In a series of freely distributed and freely downloadable critical making zines, Hertz positions critical making as an umbrella term for any art and design practice that experiments with technology in critical or non-mainstream ways: from the post-punk robotics of the 1980s Californian Survival Research Labs collective to ‘tactical media’ art like the political graffiti-spraying robots of the Institute of Applied Autonomy, the ‘critical engineering’ of the homonymous collective around Danja Vasiliev and Julian Oliver, to the ''critical design'' of Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby (which Ratto differentiates from his own concept of critical making). | |||

===critical making as a design ethos=== | |||

<div class="no-indent">Design educators often fail to see a difference between critical making and design education as it has been practiced in art schools for many decades, since design classes often involve concepts from critical theory explored in material projects. In Ratto’s concept of critical making, however, objects made by students are not design projects, but merely makeshift devices that are discarded at the end of the class. The difference is similar to that between a social science class where concepts are temporarily visualized with drawings on a blackboard to an art class where students’ drawings are the end product.</div> | |||

Since Ratto nevertheless brings ‘making’ into university classrooms, it is not surprising that design educators conversely reclaim critical making for their own practice, in the broadest sense of the term. An example of this is the 2013 book ''The Art of Critical Making'' by the Rhode Island School of Design in which the school refers to its entire curriculum as critical making. | |||

===epilogue=== | ===epilogue=== | ||

In 2019, a bankruptcy of ''Make:'' magazine marked an end of over-optimistic expectations for maker culture. Still, the term ‘maker culture’ has stuck and makes it difficult to use critical | <div class="no-indent">In 2019, a bankruptcy of ''Make:'' magazine marked an end of over-optimistic expectations for maker culture. Still, the term ‘maker culture’ has stuck and makes it difficult to use critical making for practices outside or beyond maker spaces.</div> | ||

===references=== | ===references=== | ||

Bogers, Loes and Letizia Chiappini, eds. ''The Critical Makers Reader''. INC Reader 12. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2019, | <div class="referencing">Bogers, Loes and Letizia Chiappini, eds. ''The Critical Makers Reader''. <br> | ||

INC Reader 12. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2019, research.hva.nl/en/publications/fe892f5e-c7b9-4a1a-9b76-1674562d56f0.</div> | |||

Hertz, Garnet. | <div class="referencing">Hertz, Garnet. ''Critical Making''. Vancouver: Telharmonium, 2012.</div> | ||

<div class="referencing">Hertz, Garnet. ‘Two Terms: Critical Making + D.I.Y.’ ''conceptlab.com'', 2020. conceptlab.com/2terms/pdf/hertz-2terms-202011181901.pdf.</div> | |||

<div class="referencing">Lorde, Audre. ''The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House''. London: Penguin, 2018.</div> | |||

<div class="referencing">Maeda, John. ''The Art of Critical Making: Rhode Island School of Design on Creative Practice''. Edited by Rosanne Somerson and Mara Hermano. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2013.</div> | |||

Ratto, Matt | <div class="referencing">Ratto, Matt. ‘Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.’ ''The Information Society'' 27, no. 4 (2011), <br> | ||

pp. 252–60.</div> | |||

< | <div class="referencing">Ratto, Matt, and Megan Boler, eds. ''DIY Citizenship: Critical Making'' <br> | ||

''and Social Media''. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014.</div> | |||

Latest revision as of 09:19, 27 April 2022

critical making

Critical making has a cultural and material affinity to maker culture and simple-to-use digital technologies (such as Open Source software, social media and 3D printing) that are thought to foster

a culture of ‘diy citizenship’.[3] In critical making, these technologies are not only used to bridge thinking and making, but also to introduce elements of design education into social sciences at universities.

Critical making knows at least three different definitions and schools:

- critical making developed and practiced in and for social sciences at the University of Toronto by Matt Ratto and his research team;

- critical making as socially engaged maker culture, practiced by Garnet Hertz and his research team at Emily Carr University in Vancouver;

- critical making as a design ethos, proposed and practiced among others at the Rhode Island School of Design.

critical making in social sciences

by ginger coons, who completed her PhD research in the critical making Lab of University of Toronto:

critical making, in this school, is a practical study and research method for students and scholars with no art, design or engineering background to do part

of their classroom study through material experimentation instead of only reading and discussing texts.

Open Source and Internet ‘maker’ technologies dramatically lower the threshold for non-experts

to build something—an object, a piece of technology, an application—to serve as a temporary, experimental, and discursive device for studying and exploring a concept or theory.

A cultural studies or feminist theory class, for example, could use critical making as a classroom method to study and discuss the claim of the African American poet and critic Audre Lorde that ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’,[4] by practically experimenting with the possibilities and limitations of using corporate social media platforms such as YouTube and Instagram

for anti-corporation political activism.

critical making as socially

engaged maker culture

in more than forty countries. From the perspective of digital media artists, ‘maker culture’ boiled down to

a mainstreaming and commercialization of radical technological diy that had existed from Nam June Paik’s self-constructed video synthesizer in the 1960s to, among others, artists’ experiments with self-built radio and tv infrastructures in the 1970s and 1980s, and the ‘tactical media’ movement of the 1990s.

This difference in politics is epitomized by a cover of Make: magazine (vol. 25, 2011) and its parody, Made: by the designer and artist Garnet Hertz (2012):

In a series of freely distributed and freely downloadable critical making zines, Hertz positions critical making as an umbrella term for any art and design practice that experiments with technology in critical or non-mainstream ways: from the post-punk robotics of the 1980s Californian Survival Research Labs collective to ‘tactical media’ art like the political graffiti-spraying robots of the Institute of Applied Autonomy, the ‘critical engineering’ of the homonymous collective around Danja Vasiliev and Julian Oliver, to the critical design of Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby (which Ratto differentiates from his own concept of critical making).

critical making as a design ethos

Since Ratto nevertheless brings ‘making’ into university classrooms, it is not surprising that design educators conversely reclaim critical making for their own practice, in the broadest sense of the term. An example of this is the 2013 book The Art of Critical Making by the Rhode Island School of Design in which the school refers to its entire curriculum as critical making.

epilogue

references

INC Reader 12. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2019, research.hva.nl/en/publications/fe892f5e-c7b9-4a1a-9b76-1674562d56f0.

pp. 252–60.

and Social Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014.