Contributors

- Anja Groten

- Maisa Imamović

- Heerko van der Kooij

- Juliette Lizotte

- Karl Moubarak

- André Fincato

- Loes Bogers

- Pernilla

- Stefanie

- Olivia

- Erin

- Naomi

- Gabriel

- Gerko & Julia

- Heike Roms

- Anja Groten

- Zon & Katherine

- Sarah Garcin

- Nienke & James

- Angela

- Suzanne

- Mio & Johanna

- Read-in (..)

- Jessica & Yasmin

- Jara

- Petra

- Lale

- Lulu

- Sandy

- Sally

- Siwar

- Mannetta & Joana

- fanfare

- Name

- Name

- Name

- Name

Introduction

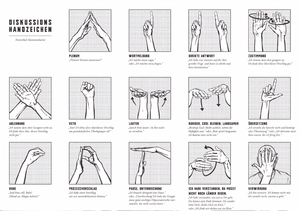

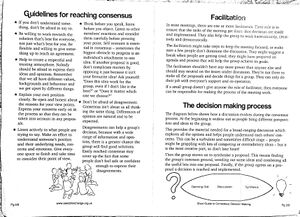

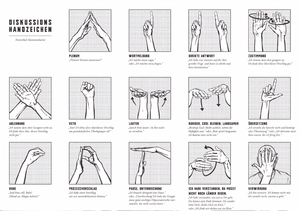

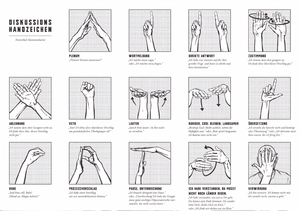

In her talk "The Workshop as an Emancipatory Mediation Method of Resistant Practices" political activist Hanna Poddig referred to the

discussion scores that are also common in Consensus Decision-making practices

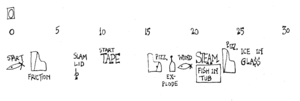

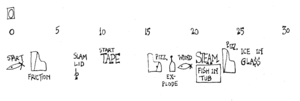

"A section of Water Walk," score by John Cage

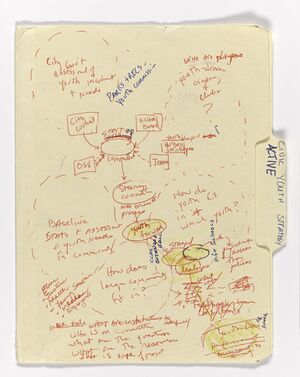

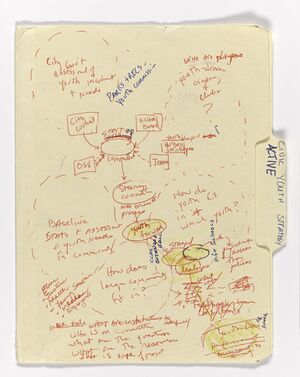

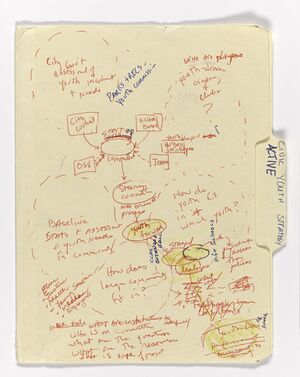

Notes by Suzanne Lacy on the ongoing civic engagement in Oakland and the Oakland Youth Policy Initiative. Image courtesy of Suzanne Lacy.

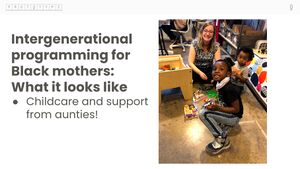

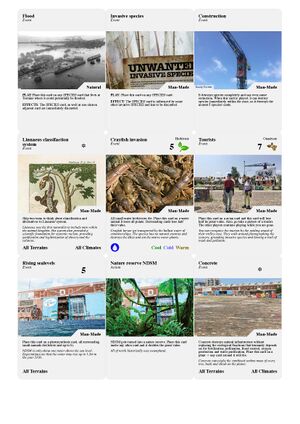

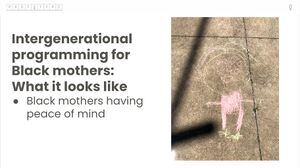

The workshop and conceptual framework of 'open-source parenting' was developed as part of 'Solarpunk—Who owns the Web?'—a collaborative exploration resulting in a series of intergenerational online and offline workshop formats. Partner organizations were Hackers & Designers in Amsterdam (The Netherlands), Mz* Baltazar’s Laboratory in Vienna (Austria) and Prototype PGH in Pittsburgh (USA). Along with the development of a series of solar punk workshops, the aim was to engage in an active peer exchange and support each other in the process of developing context-sensitive learning formats.

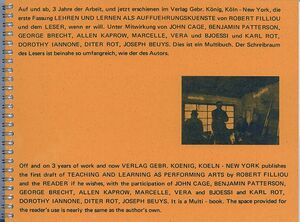

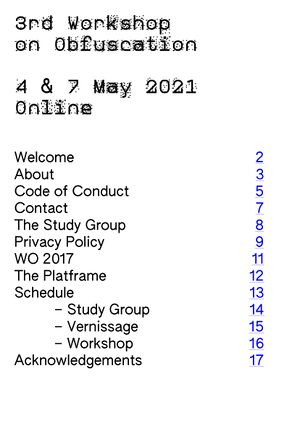

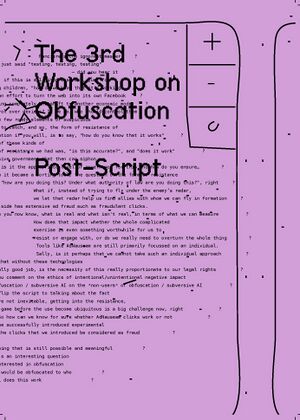

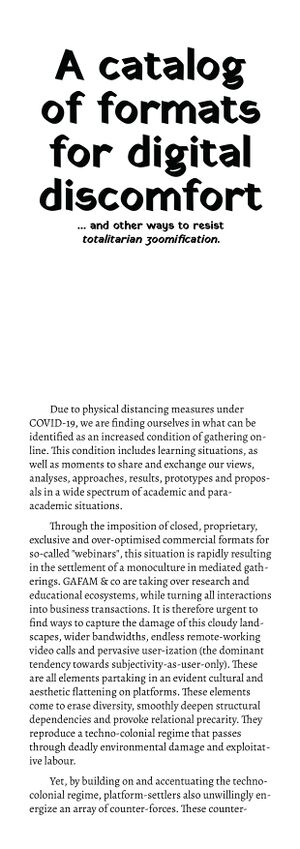

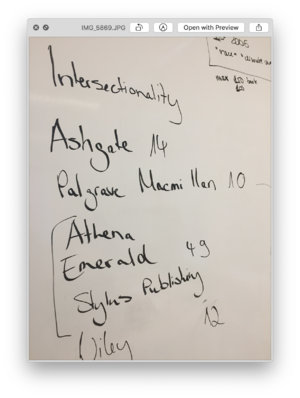

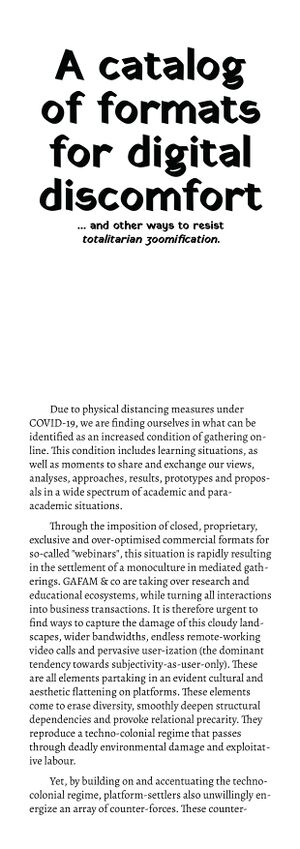

The “catalog of formats for digital discomfort” was catalogued by Jara Rocha, edited by: Seda Gürses and Jara Rocha. Accompaniment by: Femke Snelting, Helen Nissenbaum, Caspar Chorus, Ero Balsa. The first booklet version of this catalog was co-produced by the

Obfuscation event series organizing committee, Digital Life Initiative at

Cornell Tech,

BEHAVE’s ERC-Consolidation Grant and the Department of Multi Actor Systems (MAS) at the Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management at

TU Delft, in February 2021. In collaboration with the

Institute for Technology in the Public Interest (TITiPI), the Catalog is transforming into an editable MediaWiki form. Copyleft with a difference note to whoever encounters A catalog of formats for digital discomfort... and other ways to resist totalitarian zoomification: this is work-in-progress, please join the editing tasks! You are also invited to copy, distribute, and modify this work under the terms of the Collective Conditions for (re-)use

(CC4r) license, 2020. It implies a straightforward recognition of this Catalog’s collective roots and is an invitation for multiple and diverse after lifes of the document:

Downloadable pdf and

wiki version of this catalog. Referenced projects and materials, each hold their own license.

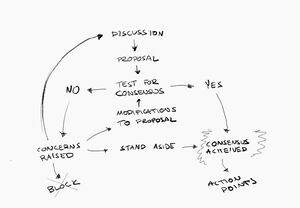

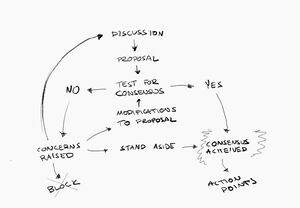

A basic diagram for doing consensus

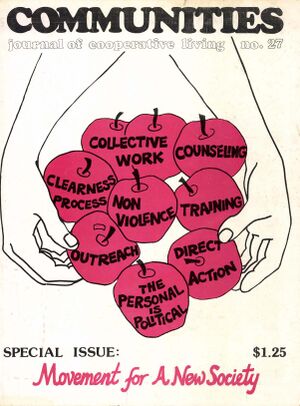

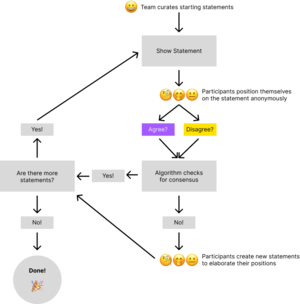

Flowchart of the discussion process

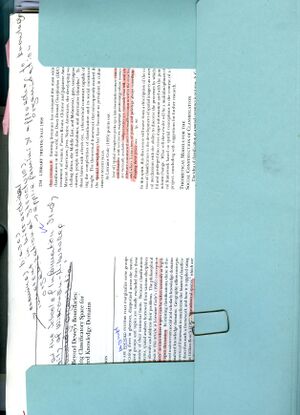

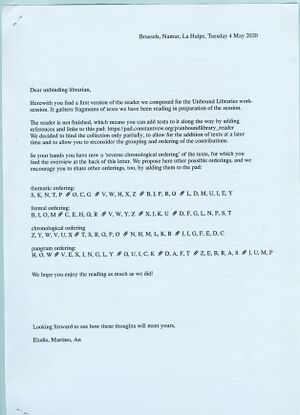

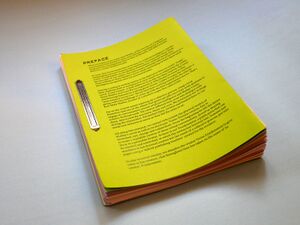

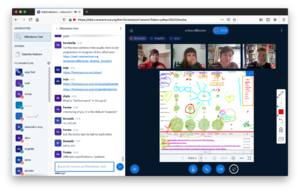

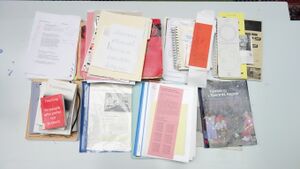

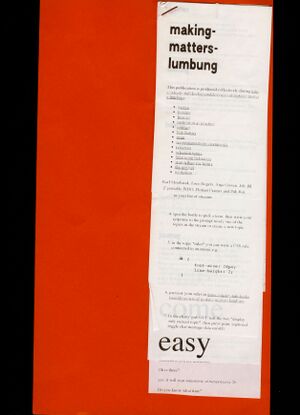

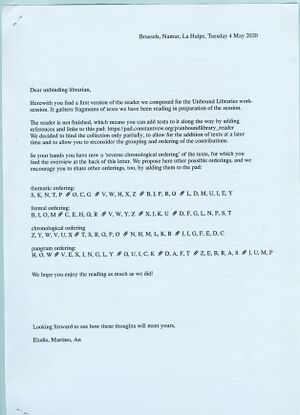

The “Unbound Libraries” folder arrived in 2020 at the H&D studio in Amsterdam. It was sent to us by Elodie, Martino and An of CAssociation for Arts and Media in Brussels in preparation for a one week work session. The work session “Unbound Libraries” took place online due to the global COVID-19 pandemic. The folder contained preparatory reading materials related to the session. It had a navigation system stapled to its front cover—an overview of the materials and a suggestion on how to approach them. It was not a fixated, bound reader but a loose collection—a repository of materials that can grow and changes over time. More information can be found on

https://constantvzw.org/wefts/unboundlibraries_materials_index.en.html and

https://feministsearchtools.nl/

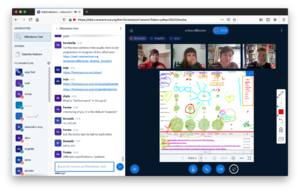

Screenshot of the Unbound Libraries work session

Screenshot of the Unbound Libraries work session

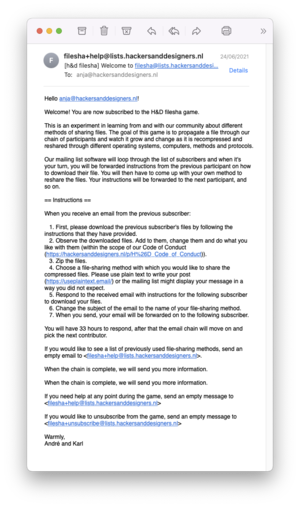

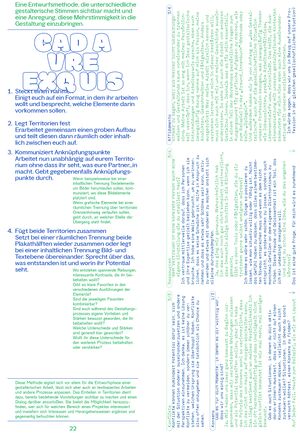

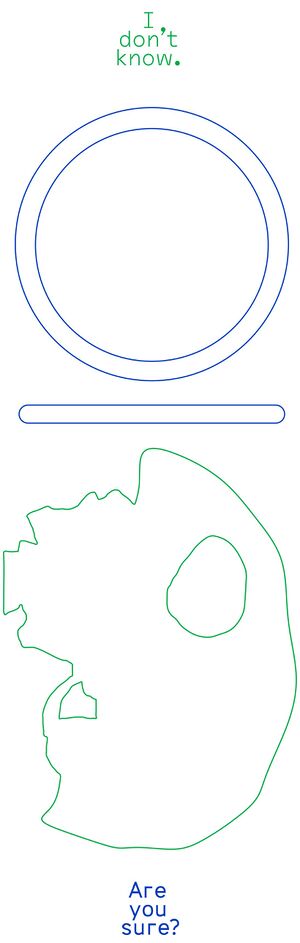

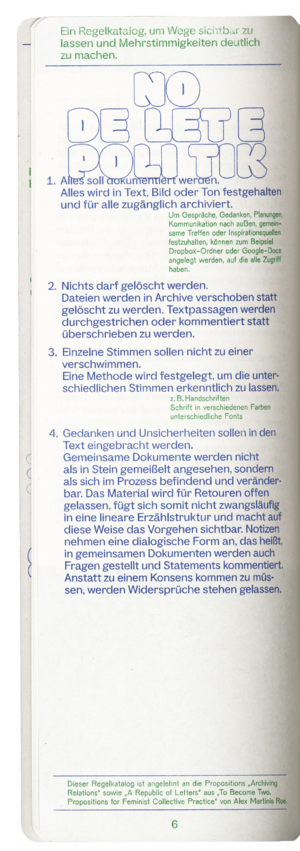

"I don’t know. Are you sure?" searches for a way of working together that actively engages with friction and appreciates differences instead of seeking the comforts of compromise and middle ground. The collection of fifteen collaborative methods is accompanied by short interviews reflecting on topics such as conflict, sharing skills and resources, and the resilience. A free pdf can be downloaded here:

http://miokojima.com/idontknow-areyousure/idk-ays.pdf

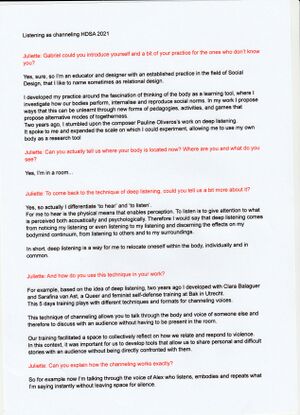

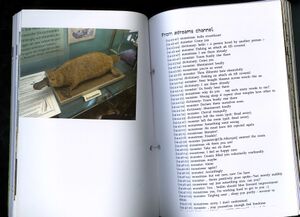

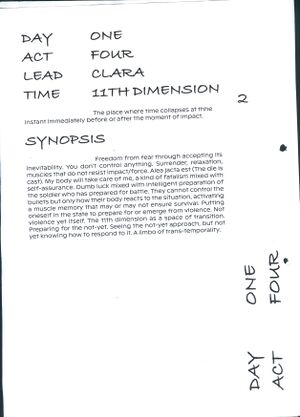

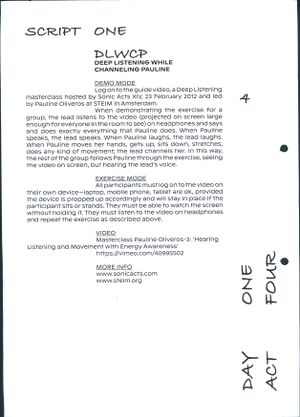

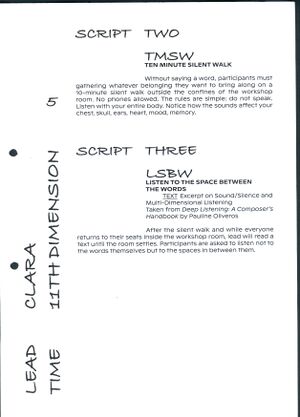

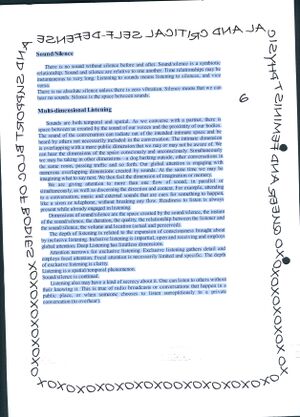

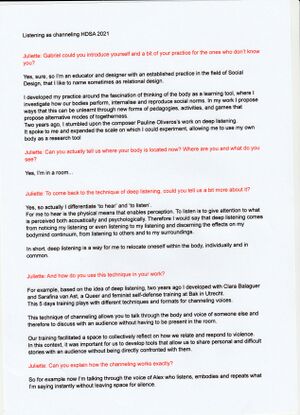

Channeling performance script, H&D Summer Academy 2021, Gabriel Fontana

|

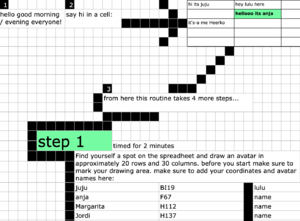

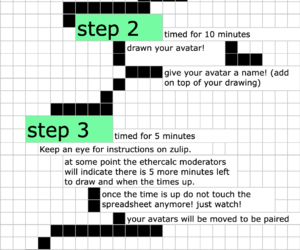

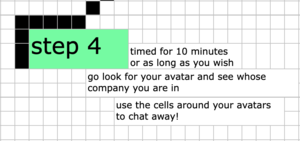

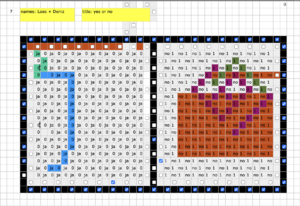

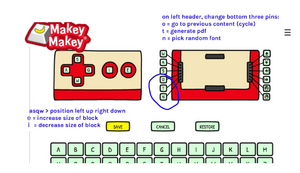

Character making in Ethercalc

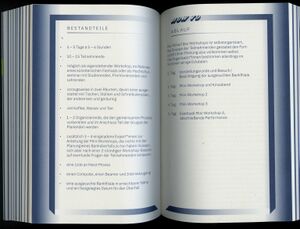

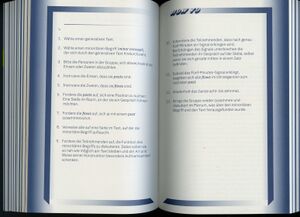

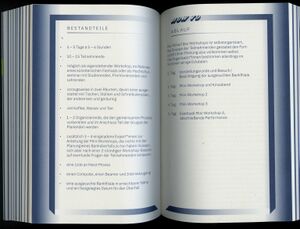

How-to "The Perfect Robbery" by Juli Reinartz," in

Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook, edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).

How-to "Give and Take" by Social Muscle Club," in

Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook, edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).

How-to "Conceptual Speed Dating" by Brian Massumi," in

Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook, edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).

How-to "Bodystrike" by Feminist Health Care Research Group," in

Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook, edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).

How-to "Bodystrike" by Feminist Health Care Research Group," in

Learning to Experiment, Sharing Techniques: A Speculative Handbook, edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert (Weimar/Berlin: Nocturne, 2020).

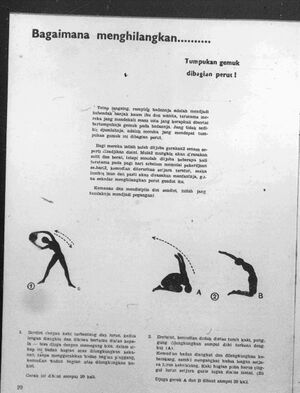

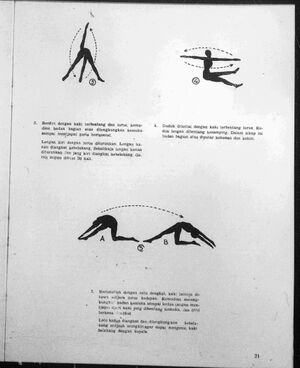

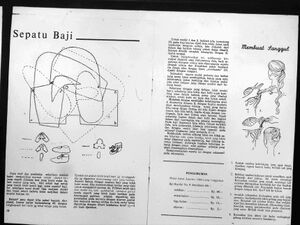

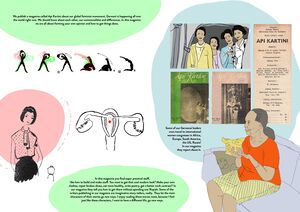

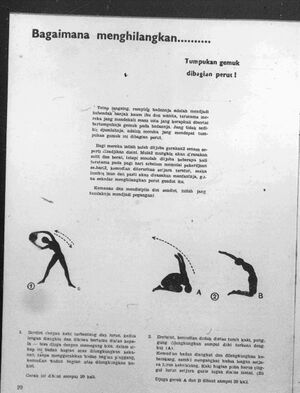

Page from scanned microfiches, “Api Kartini Djakarta: Jajasan Melati,” 1959-1964, Leiden University Library, Special Collection.

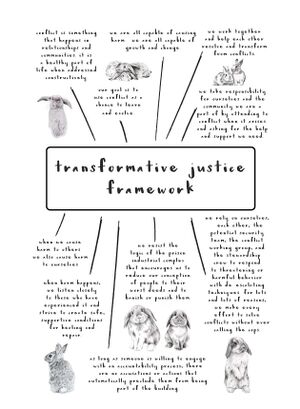

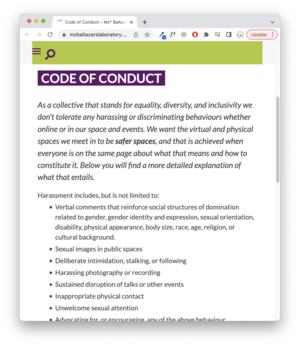

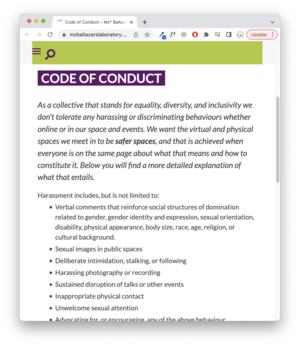

Code of conduct of Mz* Baltazhar's Lab. One of the "Solarpunk" work sessions focussed on the partner organizations' code of conducts, in which the divergences and similarities of the different contexts of Hackers & Designers, Prototype Pittsburgh and Mz* Baltazhar's Lab were discussed. CoC Mz*Baltazar’s Lab

https://www.mzbaltazarslaboratory.org/code-of-conduct/

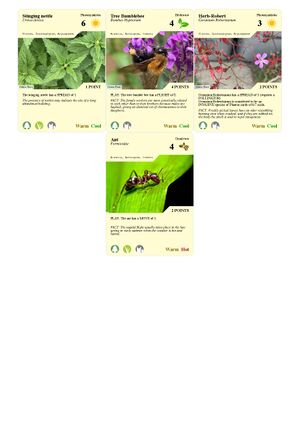

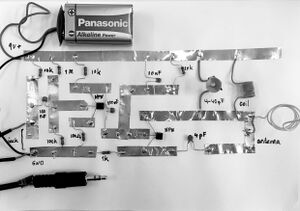

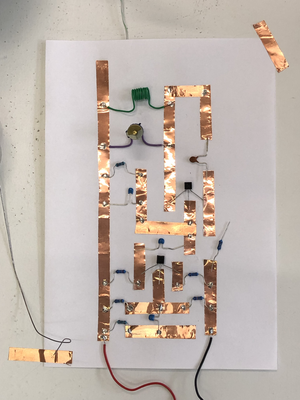

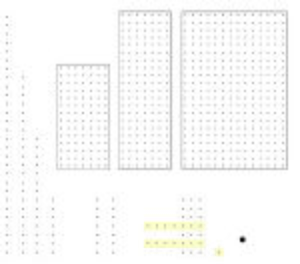

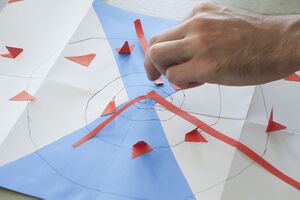

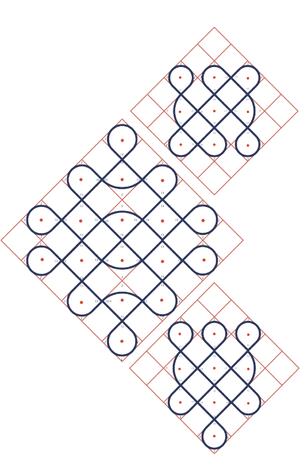

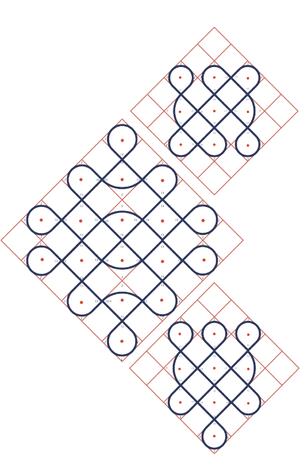

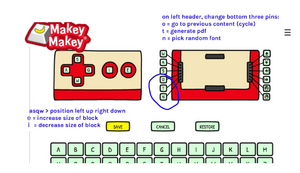

Technical drawing of the different components of the fanfare display system

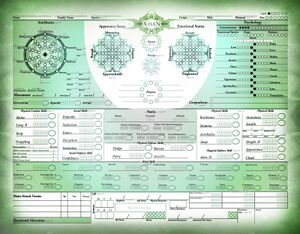

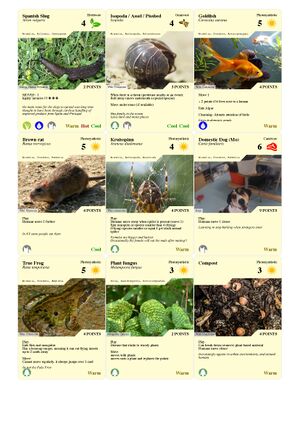

Phylomon card deck (HDSA–Amsterdam edition)

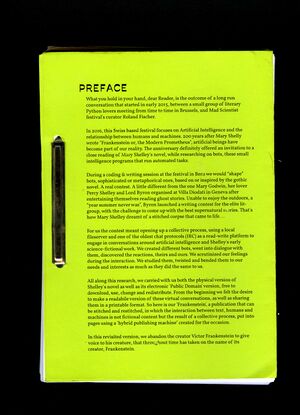

Publication collectively made by Algolit: Piero Bisello, Sarah Garcin, James Bryan Graves, Anne Laforet, Catherine Lenoble, An Mertens, bots and PJ Machine

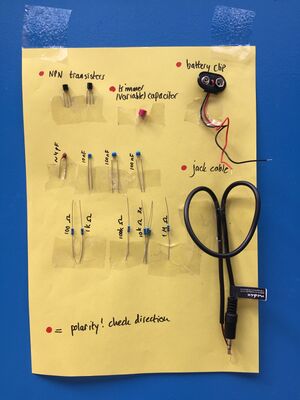

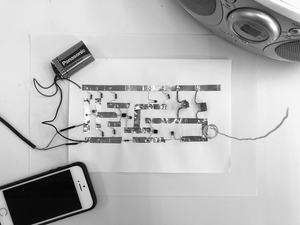

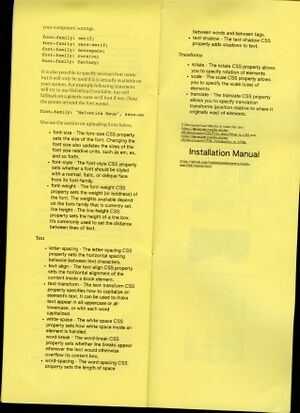

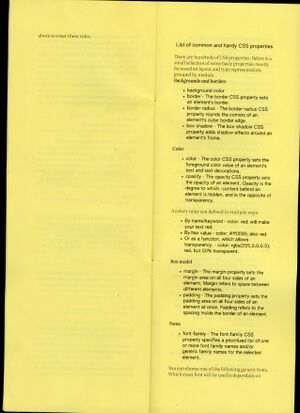

Documentation and user manual of the workshop "ctrl-c" at HFG Karlsruhe. During the hands-on workshop participants investigated ways to take apart and reassemble remote controllers and other battery powered toys in unusal ways. By saving redundant electronics from becoming e-waste we hacked our way into the mechanics of human computer interaction and user interfaces. At the same time we learned about electronics–all the while critically reflecting on the notion of control. The toy-tools were documented by participants in the form of a user manual that explained and demonstrated the main functionalities

See “Interfacial Workout,” Hackers & Designers, October 24, 2019,

https://hackersanddesigners.nl/s/Activities/p/Interfacial_Workout "Interfacial Workout," and “Workshop ctrl-c HFG Karlsruhe,” YouTube, May 24, 2018, https://youtu.be/T4YkgIshzVg, and “Workshop ctrl-c HFG Karlsruhe – 2,” YouTube, May 24, 2018, https://youtu.be/_rJZJrS40tc

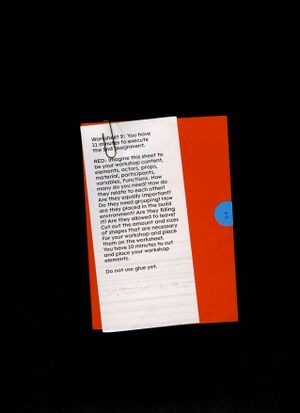

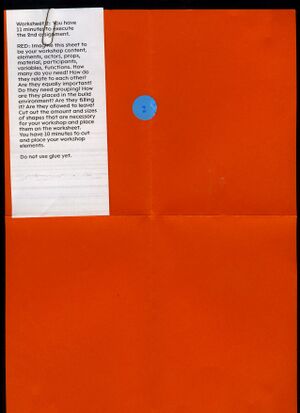

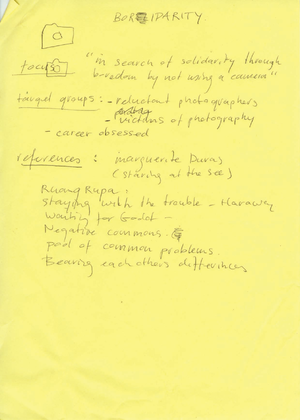

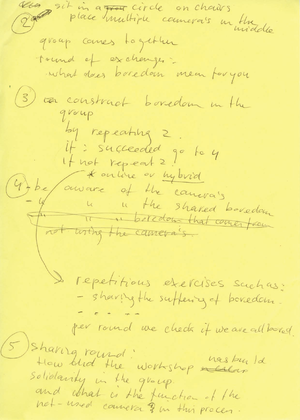

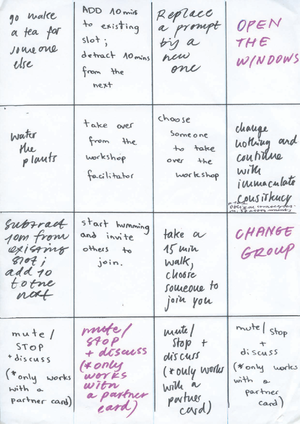

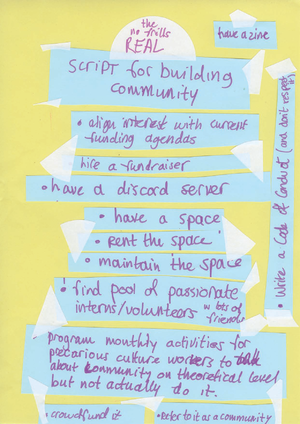

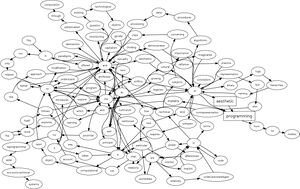

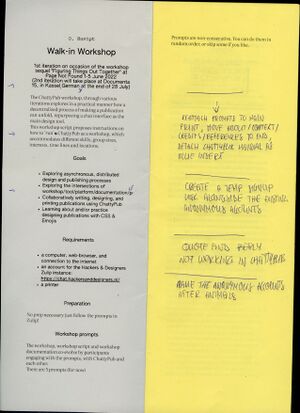

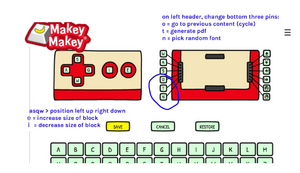

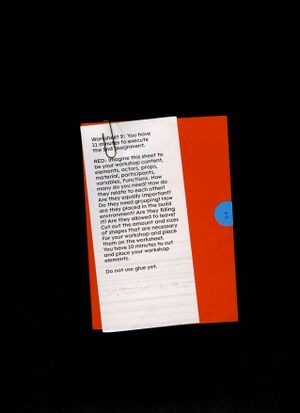

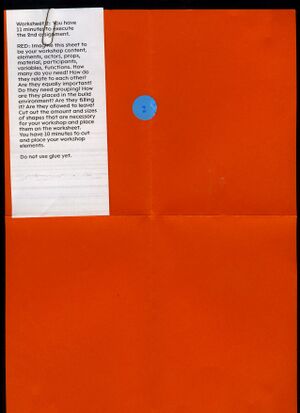

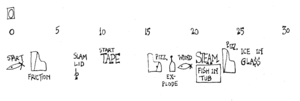

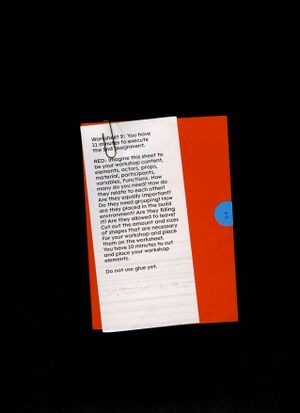

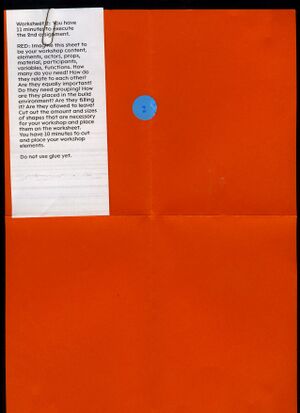

Worksheet for “An Automatic Workshop,” collaboration with Shailoh Philips during the H&D Summer Academy 2018, Amsterdam

Worksheet for “An Automatic Workshop,” collaboration with Shailoh Philips during the H&D Summer Academy 2018, Amsterdam

Worksheet for “An Automatic Workshop,” collaboration with Shailoh Philips during the H&D Summer Academy 2018, Amsterdam

Worksheet for “An Automatic Workshop,” collaboration with Shailoh Philips during the H&D Summer Academy 2018, Amsterdam

Worksheet for “An Automatic Workshop,” collaboration with Shailoh Philips during the H&D Summer Academy 2018, Amsterdam

Worksheet for “An Automatic Workshop,” collaboration with Shailoh Philips during the H&D Summer Academy 2018, Amsterdam

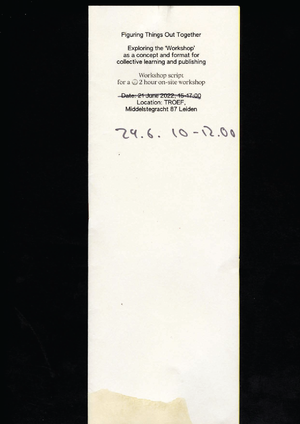

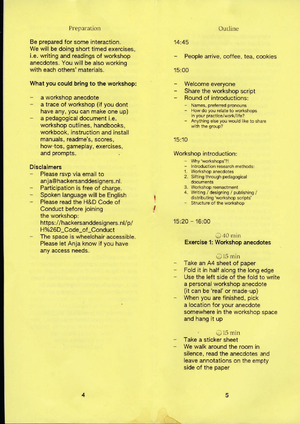

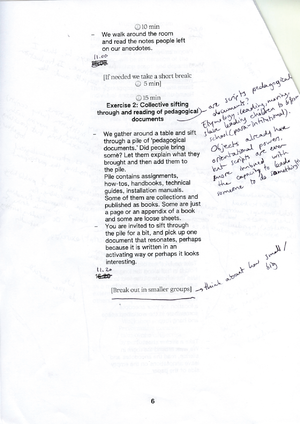

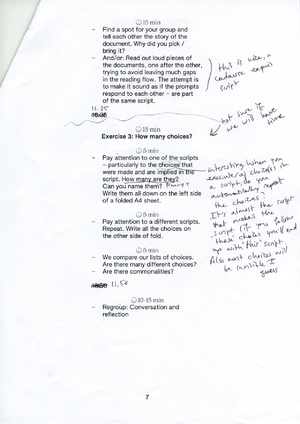

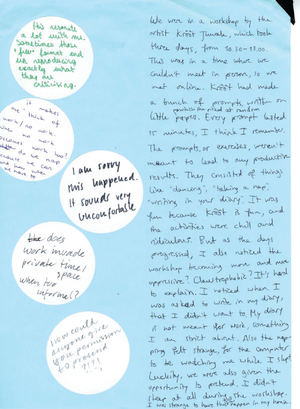

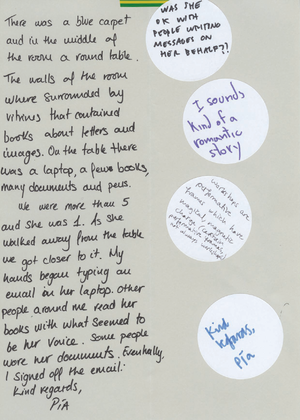

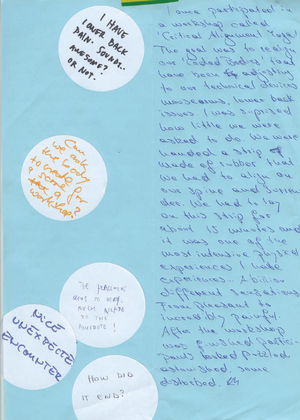

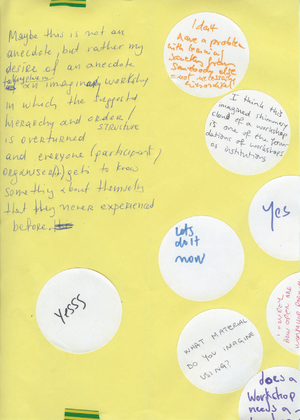

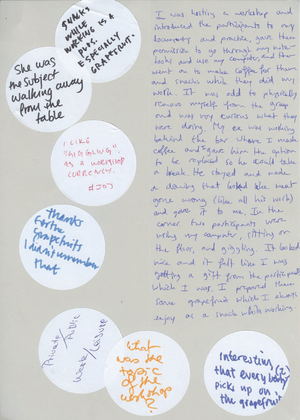

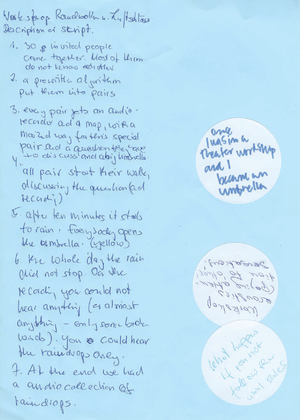

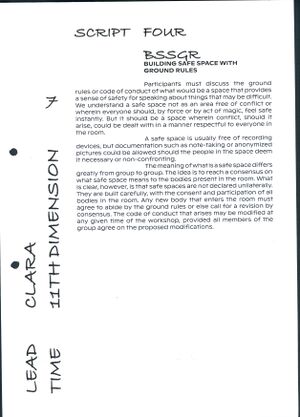

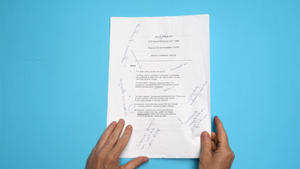

Script annotations by Pia Louwerens, Workshop reenactment, Troef Leiden, June 2022

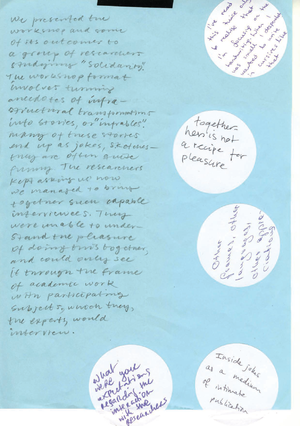

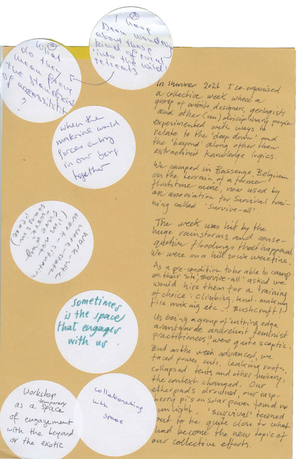

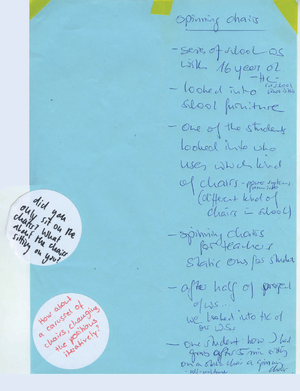

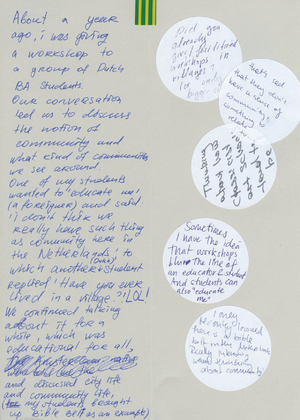

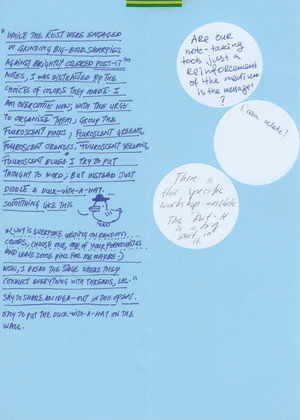

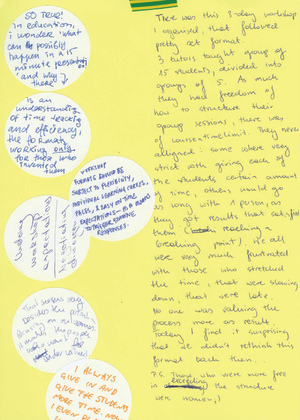

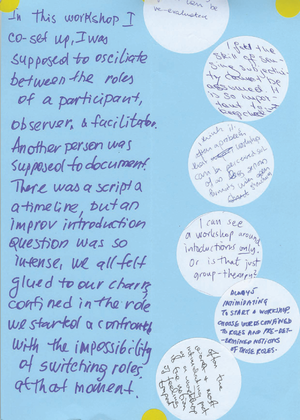

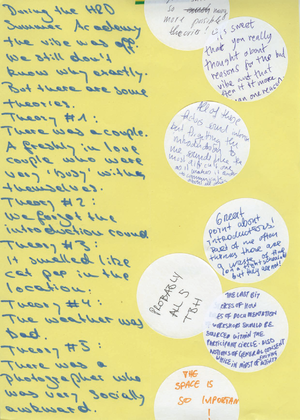

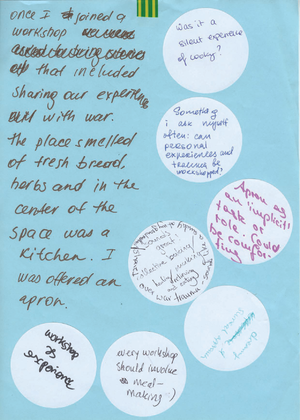

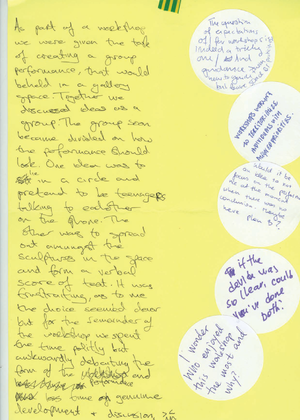

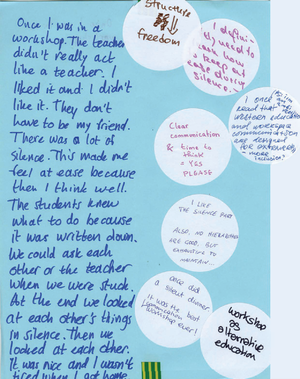

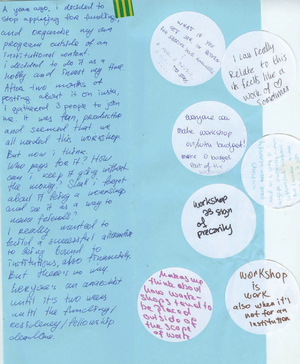

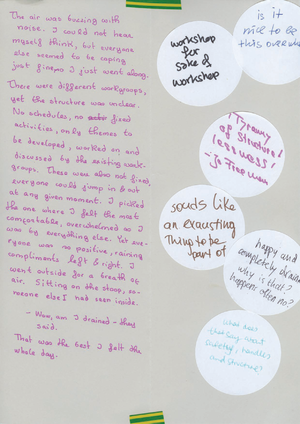

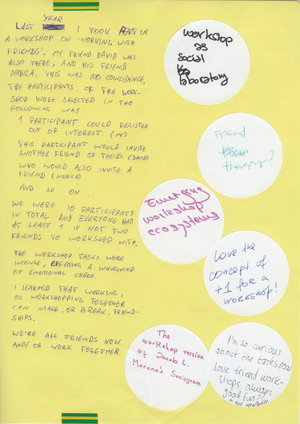

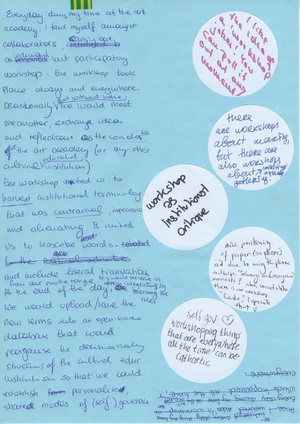

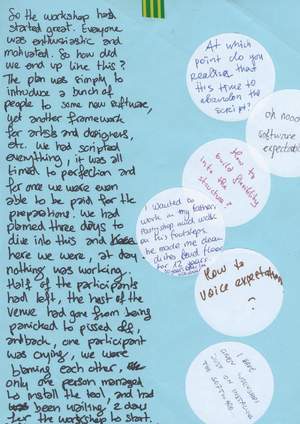

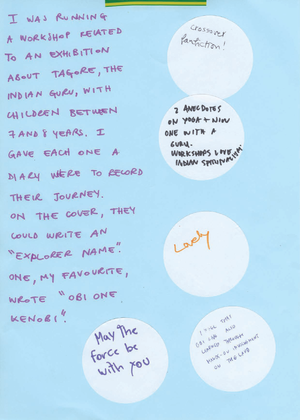

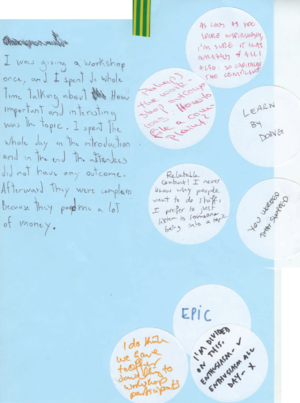

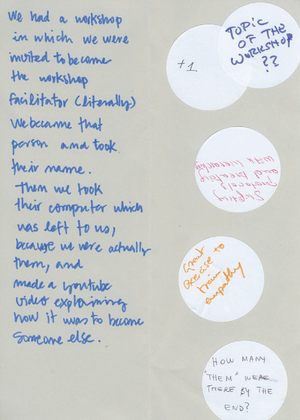

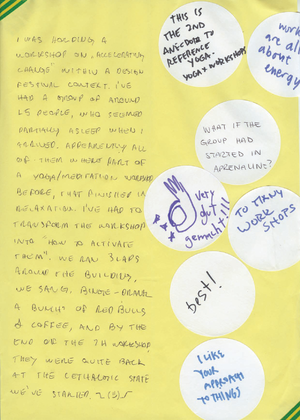

Workshop anecdotes, written by workshop participants, June 2022

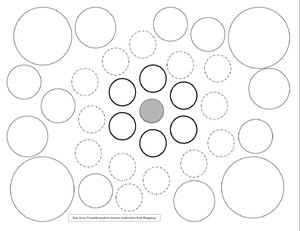

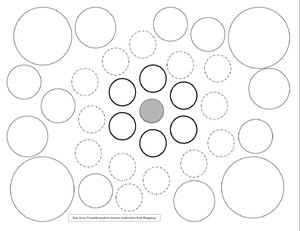

Pod Mapping: During one of the first work sessions with H&D, Mz* Baltazar and Prototype Pittsburgh, Pernilla proposed to try the method "Pod Mapping" as developed by Mia Mingus for Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective (BATJC), June 2016. Find more information about the method and the worksheet:

https://batjc.wordpress.com/resources/pods-and-pod-mapping-worksheet/

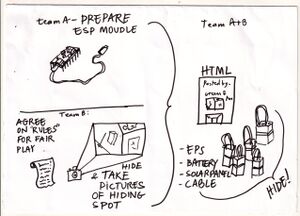

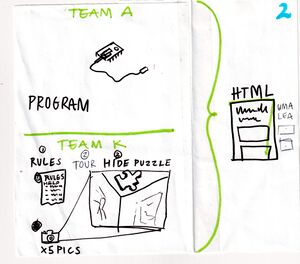

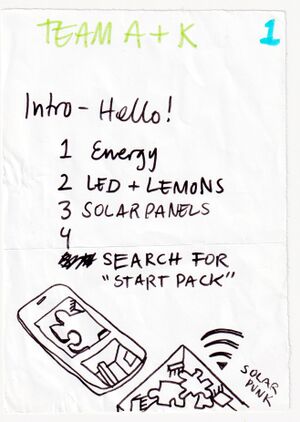

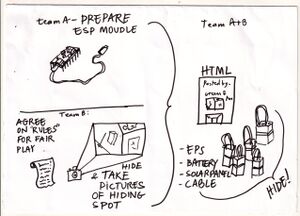

Sketch of workshop setup and game

Short version of the H&D Code of Conduct. One of the "Solarpunk" work sessions focussed on the partner organizations' code of conducts, in which the divergences and similarities of the different contexts of Hackers & Designers, Prototype Pittsburgh and Mz* Baltazhar's Lab were discussed.

https://hackersanddesigners.nl/p/H%26D_Code_of_Conduct

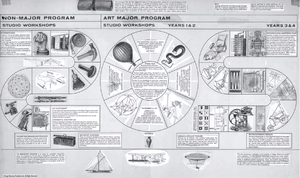

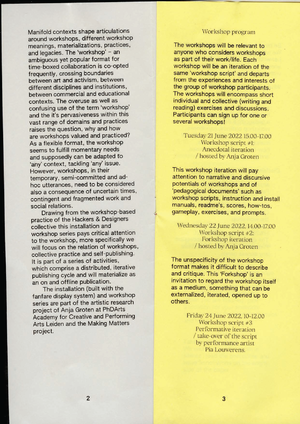

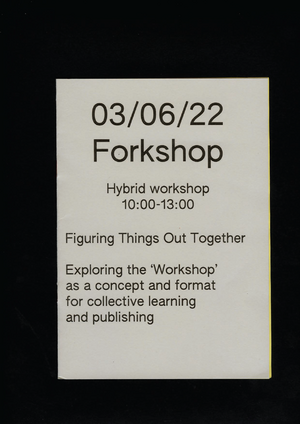

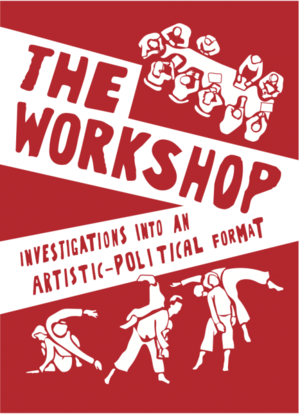

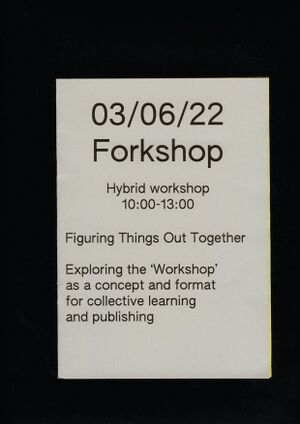

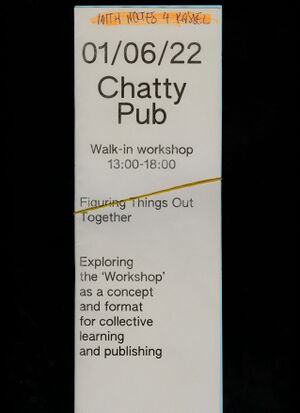

Presentation Poster designed by Workshop Project

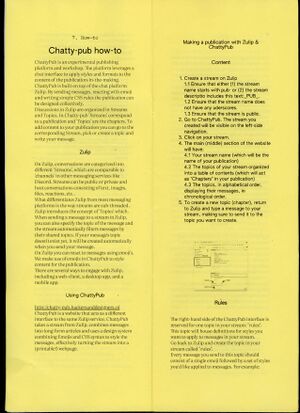

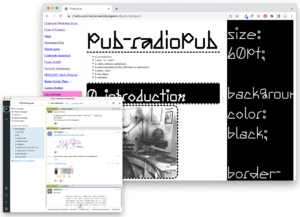

Documentation made in ChattyPub during HDSA2021

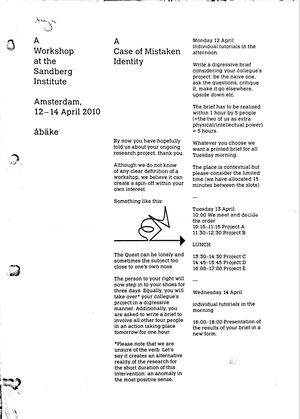

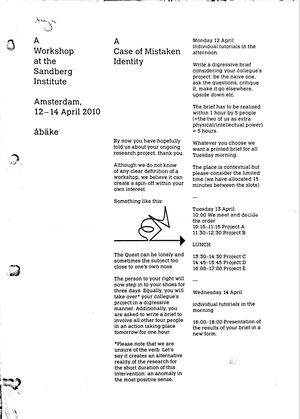

åbäke's Workshop assignment "A Case of Mistaken Identity," 2010

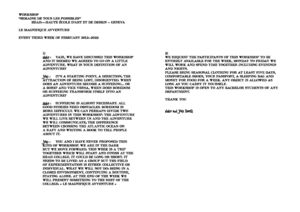

Prompt “Le Magnifique Avventure,” Yaïr Barelli, Maki Suzuki, 2012

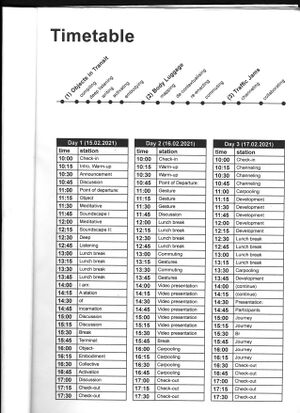

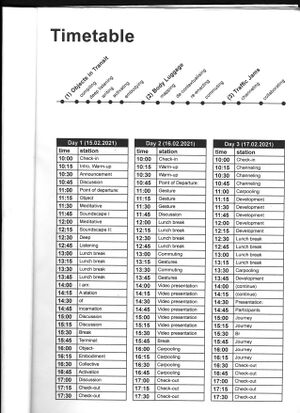

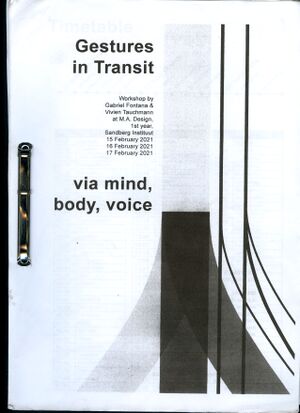

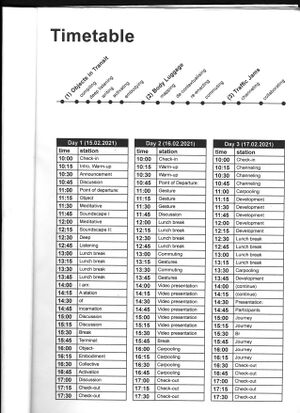

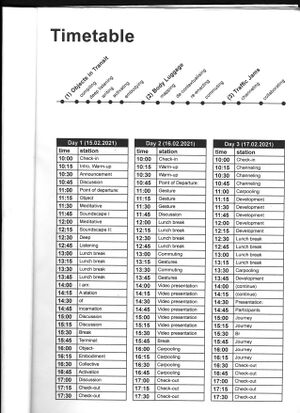

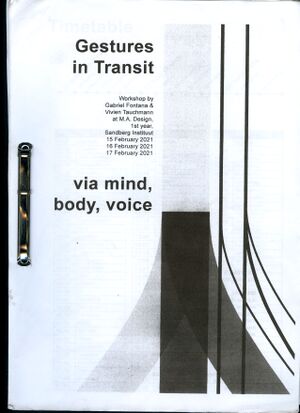

Page from Workshop manual "Gestures in Transit," Gabriel Fontana, Vivien Tauchmann, 2021

Page from Workshop manual "Gestures in Transit," Gabriel Fontana, Vivien Tauchmann, 2021

Page from Workshop manual "Gestures in Transit," Gabriel Fontana, Vivien Tauchmann, 2021

First, Then… Repeat.

Workshop scripts in practice

Hackers & Designers (ed. Anja Groten)

Introduction

Compress your files. Pick a story. Form a circle. Find yourself a spot on the spreadsheet. Write an anecdote. Run the script. Download the zip. Continue the thread. Install the package. Go on a stroll. Follow each other. Slowly. Like a worm. Rename the repository. Return. Close your eyes. Take turns. Repeat. Come prepared. Nothing to prepare. No prior knowledge required. Be kind. Don't assume. Scoop the mud. Pick a time. Wash your hands. Watch. Swap. Strip the wires. Connect. Take your time. Rearrange. Share the link. Go to line 42. Make a copy. Be patient.

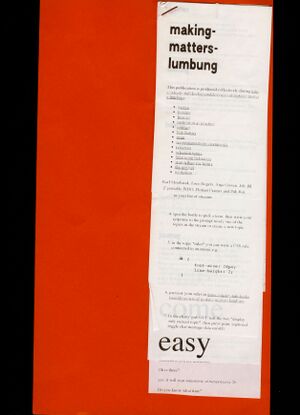

This publication draws together self-published and unpublished workshop scripts that evolved in and around the collective ecosystem of Hackers & Designers (H&D).[1] H&D has been organizing workshops since 2013, and along the way has established social-technical affinities that are loose and stable, temporary and ongoing. We met and befriended many practitioners and sister organizations since, and got acquainted with manifold, peculiar pedagogical formats, and experimental approaches to working, learning, and being together. This publication derives from an enthusiasm for the various ways collective learning environments take shape. It grew out of a curiosity for the ways that such practices are shared across different localities, timelines, and experiences.

Situated somewhere between documentation and a call for action, the workshop scripts presented here are companions to self-organized learning situations. They articulate and materialize aspects of such practice that cannot always easily be explained through existing frameworks. Contributions to this book document and reflect on self-organized learning situations that spontaneously assemble practitioners from various domains, diffusing disciplinary boundaries and blurring distinctions between learner and teacher, user and maker, product and process, friendships and work relations. They have in common that they seek affiliations beyond predetermined domains and bring together various vocabularies and methods all at once.

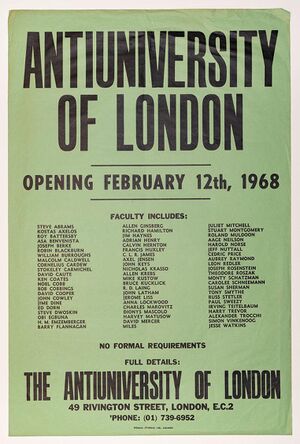

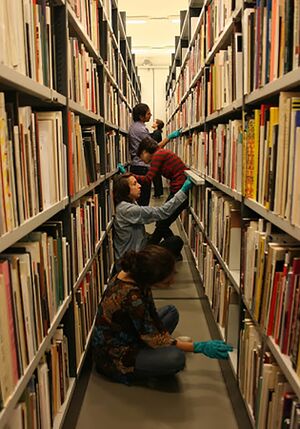

Documentation is rare, always incomplete, and it is therefore difficult to reconstruct what actually happens during such temporary collective learning communities. This is a challenge that art historian Heike Roms addresses in the conversation about workshop histories and practices, which offers a wider historical scope for some of the questions addressed in this publication. In her work, Roms is interested in the history of artist initiatives that reformed art education through self-organized educational experiments in the 1960s and ‘70s in the UK, when artists and educators began to organize study-groups for teachers and students in their private homes. Such evening classes were structured around exercises, and became a kind of parallel institution. Roms suggests this was an attempt to create an equal status between the participants. Roms also points out that conducting research into such initiatives is difficult as usually they were not well documented. The emphasis of such practices was on the momentary collective experience, and not so much on what was being produced at the end, though often there were occasions where work was publicly shared. With some luck, there might be some leftover notes or printed materials, such as announcements, flyers, posters, and pamphlets that hint at the character and content of the activity. But few notes remain from the exercises. On occasion Roms found a prompt, a class outline, or a score. However, the ways in which such prompts were perceived, enacted, and iterated on is difficult to reconstruct.

This publication addresses this challenge by drawing together workshop-based practices as a form of inquiry and by paying attention to the practice of (re)writing, (re)activating, documenting, and reflecting on “workshop scripts.” This is an attempt to discuss and show how workshops and workshop scripts shape—and in turn, are shaped by—the various environments they pass through. As a collection that holds various relational and iterative documents, it therefore cannot be considered a product or example of one specific kind of practice. The practices it draws together are site, context, and time specific, never complete, always ongoing, as are their various forms of expression.

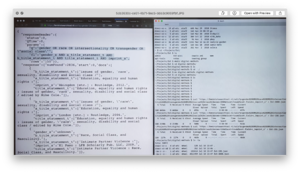

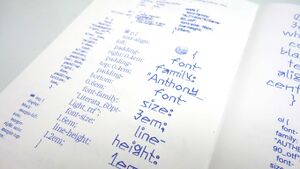

Moving through manifold contexts—from institutional to grassroots informal—H&D as a collective is constantly in the making. Along the way, we are developing “terms of transition”[2]—socio-technical conducts that help us to navigate and “stay in touch” in uncertain times. Workshop scripts are traces of such an attempt. They are ephemeral documents that may be written by hand or take shape in open-source spreadsheets and notepads, Git repositories, Wikis, and mailing lists. These documents are brought into conversation and circulation and as such reveal something about the ways collective practices weave together a range of places, legacies, objects, and people across practices and disciplines, timelines and geographies. They are pragmatic as well as imaginative, capturing approaches, techniques, and atmospheres that evolve from within specific communities and practices, while holding together the chaosmos of collective self-organization.

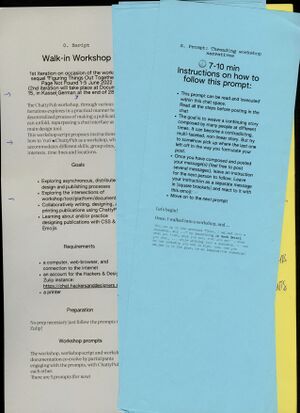

For instance, the workshop script “ChattyPub,” gives instructions on how to “run” ChattyPub as a workshop and as a platform for discussion and as a publishing tool that explores a decentralized process of designing a publication and as an organizational open-source collaboration software. The script does not solely document an instantaneous workshop situation but rather explores the intersections between workshop/tool/platform/documentation/distribution. The script is pragmatic and invites others to take it on and run with it, while accounting for its entanglements within a specific socio-technical context.

As situation-specific and context-sensitive artifacts, workshop scripts take manifold shapes and roles in this publication. Some derived from the immediate or wider context of H&D and its members, some are historical examples, and some are works of fiction. They are accompanied by—or enmeshed in—anecdotes, essays, graphic novels, speculative how-tos, and reflexive conversations that both activate and situate them within the respective communities and practices. This eclectic collection of workshop scripts reflects the continued effort of building collective ties through documentation, the practice of sharing with each other, and paying attention to the details. You won’t find a precise definition of what a workshop script is. Instead you will encounter different ways that workshop scripts are understood, materialized, and put into practice across various contexts. A workshop script may be concise or expansive; it may include instructions and install manuals, code snippets, timetables, and readmes. It may also include context-specific, personal and narrative aspects.

This publication attempts to approach these scripts and the practices they involve not as products of linear or reproducible processes but as resulting from and implied in particular socio-economic, socio-technical conditions. As such, the publication resists a generalized approach to the reproduction of these scripts. When possible, the initial appearance of the scripts, their format, and layout are left intact, forgoing the impression of a blueprint. Thus, the contributions may require some commitment, some attunement, and “getting into.”

The idea for publishing these situated documents and their stories derived from both the frustration and joy of working and being together while negotiating unstable times and conditions, and paying critical attention to the fleeting nature of formats of encounter, as well as the continuous effort of staying in touch with those who we encounter. The scripts are never finished, they always require more work. In some ways this publication can be considered a scriptothek—a script collection that continues collecting. The script + othek contains bibliotheek. In the German and Dutch languages, the Bibliothek/bibliotheek is a place of careful collecting, deciphering, making available, and preserving the documents it holds and handles. Often, it is through the work and personal investment of a Bibliothekar*in that such a place and the documents it holds are activated and brought into circulation.

My approach as an editor is inspired by that of the Bibliothekar*in. Similarly, it is also through personal and to some extent subjective affinities that I collect, decipher, preserve, and circulate the stories intertwined with the documents this Scriptothek holds. It is rooted in—and energized by—a sort of distributed locality. For instance the workshop script “A Case of Mistaken Identity” by the graphic design collective Åbäke has been sitting in a pile of pedagogical documents since I received it as a workshop participant in 2010. It has been activated throughout the years, in implicit and explicit ways, and informed my personal appreciation for collective work in and outside art and design education. As you will read in the email conversation with Åbäke, my request to republish the document in this context unraveled an array of exchanges, tasks, and prompts.

Thus, besides representing or giving visibility to specific documents and practices, publishing this eclectic collection in and of itself became a generative, ongoing, and to some extent uncontrollable collective praxis. The scripts included in this collection are time stamped. They had (or will have) a moment, a place, and a people that activate them. Simultaneously, by entering this collection they also create new correlations and future outlooks. The featured documents and practices are iterative and ongoing yet not “off-the shelf,” not to be executed and re-used in any context; they each come with their own terms of transition.

Each contribution negotiated specific terms in order to enter this book—terms of activation, contextualization, adjustment, reconsideration, be it through specific licenses that were added or even by being taken out of the public domain entirely. For instance, I invited the makers of the Not For ANY licensing toolkit to contribute some of their exercises to this publication. The Not For ANY toolkit invited “collective engagement with open licenses from a (techno)feminist perspective in a playful and embodied way [...]” and included “a series of exercises to do this with.” And yet my invitation prompted the makers to take the toolkit offline. Instead, the initial page now serves as a redirect to other groups and practices who have been more intensively continuing and complicating the conversation around open licensing. Thus the editorial process set into motion new considerations about the conditions for further sharing (or not).

Clustering

To assist the reader, the contributions are organized into five clusters: Setting Conditions, Prompts, How-tos, Distributed Curricula, and Active Bibliographies. While the contributions are organized according to these clusters and appear in a linear order, they are also intertwined in multiple ways, and resist a linear narrative (forward-moving progressing, improving, innovating). Thus, readers are invited to be on the look out for other, multiple, and parallel connections and navigate the contributions idiosyncratically, non-linearly, in a zigzag, from back to front.

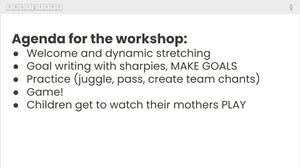

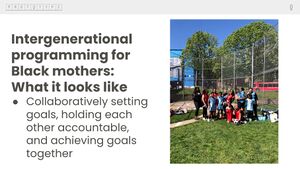

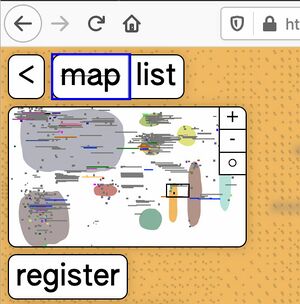

The cluster Setting Conditions pays attention to the specificity of self-organized collective learning environments, their site and context specific vocabularies, and social-technical conduct. The aforementioned conversation between Anja Groten and Heike Roms sketches a larger (historical) context and sets the scene for the contributions that follow. The contribution “Open-Source Parenting” by Naomi Walker and Erin Gatz of Prototype Pittsburgh, takes a “first things first” approach and attends to the conditions that need to be in place before being able to create or engage in any form of learning community. In their conversation, Erin and Naomi reflect on how Black women in Pittsburgh are creating a better future for themselves and how allies can support them in this work. The “Platframe Postscript” compiled by Anja Groten and Karl Moubarak reflects on the collective process of building an online workshop environment that converges various tools and practices in a manner that sustains their “contours.” Throughout the process of imagining, building, and activating this digital infrastructure the edgy term “platframe” reminded the collaborators that this online environment they are building together consists of many parts, which do not necessarily blend together nor are they experienced as seamless.

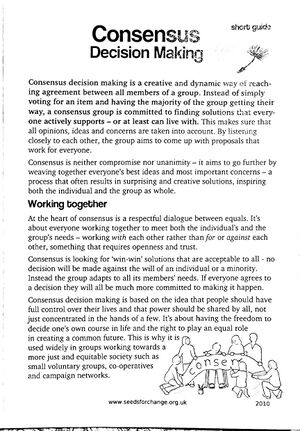

Angela Jerardi discusses consensus-decision making models and practices, contextualizes them historically and in relation to contemporary activist communities. The project “WIN WIN” by James Bryan Graves and Nienke Huitenga-Broeren concretely and imaginatively explores conditions in which less polarized online debate is possible by proposing a consensus-based algorithm that mediates controversial discussion and collective decision making.

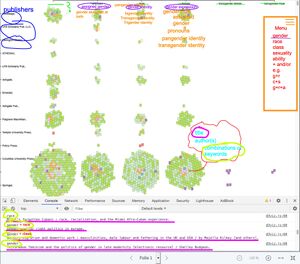

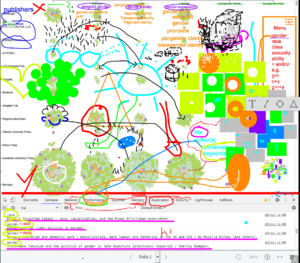

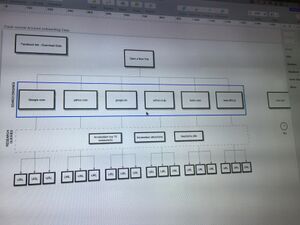

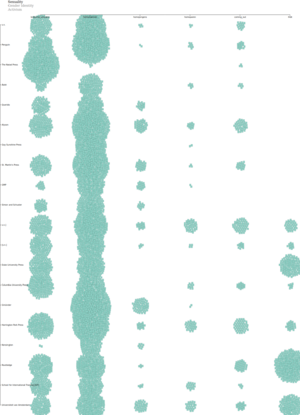

In “Re-, and Undefinining Tools,” the Feminist Search Tools (FST) workgroup reflects on the slow collective process of building, narrating, and testing an ongoing and evolving library search tool through various workshops, and meetups in various contexts and constellations. This non-conclusive process creates a condition in which various context-specific definitions of tools can be expressed, as well as criteria for the usefulness or usability of such tools. In the following contribution, Qianxun Chen sets new conditions for the FST conversation. The generative textual system “Mycelines” brings to the fore recurring terminology and formulations that evolved from this collective reflection on a tool-building process. In “fileSHA as a Protocol” André Fincato and Karl Moubarak set the conditions for an asynchronous game by repurposing mailing list software.

Within the cluster Prompts inhabit concise propositions and calls for action. Prompts can be playful provocations, invitations to reconsider, to change direction; a proposal to approach something familiar differently. The contribution “Across Distance and Difference” takes into consideration the changing economic and material realities of Mio Koijma and Hanna Müller, who formulate small assignments for each other as an attempt to structure and sustain their collaboration in times and conditions that seem to work against their efforts. Sandy Richter reflects on her experience of participating in a workshop during the H&D Summer Academy (HDSA) 2021, during which it was not immediately evident what the prompt was, who the host was, and who was the participant, or observer/listener. Through her reflection, the prompt of the workshop host Gabriel Fontana, is slowly unraveling.

The prompts of the “Relearning Food” script challenge participants to pay attention to the routes our produce takes to reach supermarkets and eventually our plates. Their prompt is to reconsider grocery habits according to our geographies and localities. In her essay “Untitling”, Siwar Kraytem substitutes short anecdotes on the subject and practice of naming with prompts to trigger a discussion on the politics of naming.

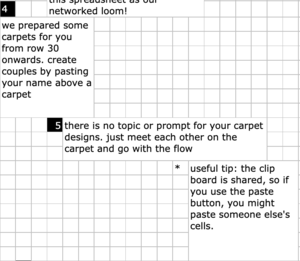

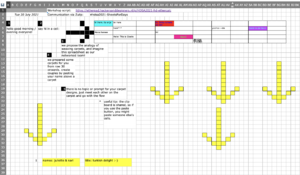

The prompts of the “Spreadsheet Routines” by Anja Groten and Karl Moubarak as well as the “Etherpad roleplay” by Juliette Lizotte both utilize playful open-source collaborative writing and editing tools, which serve as workshop sites, which weave together prompt, method, and execution into an evolving collective techno-social narrative. Susan Ploets' LARP (Live Action Roleplay) script, “Skinship,” prompts participants to explore the condition of being a collective body that inhabits, shapes and is shaped by an environment through sensory information.

The contributions collected within the cluster How-to explore the tension between the pragmatism of workshop scripts on the one hand, and the imaginative, fictional aspects at work in such documents on the other. The contribution by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert offers a generous and comprehensive backdrop to the format and role of the how-to as it is explored in art, art education, and activism. They draw on several concrete examples of how-tos such as “The perfect robbery” by Juli Reinartz and Tea Tupajic, “Give and Take” by the Social Muscle Club, “Conceptual Speed Dating” by Brian Massumi, and “Bodystrike” by the Feminist Health Care Research Group. These prompts derive from a compendium of how-tos, the publication Experimente Lernen, Techniken Tauschen edited by Julia Bee and Gerko Egert, and the accompanying platform Nocturne. According to Julia and Gerko, “the logic of speculative pragmatism allows us to think of techniques not as something one needs to earn, or learn to master, but as a way to put into practice speculation in the midst of an actual situation.”

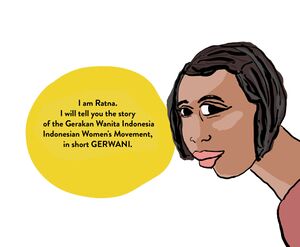

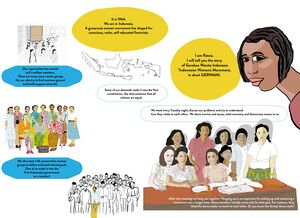

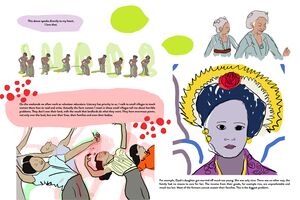

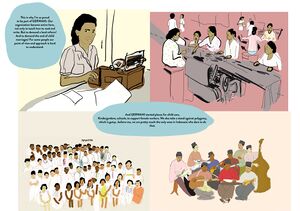

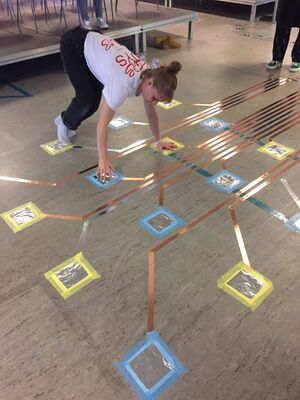

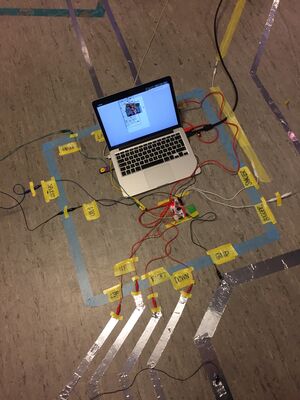

Similarly, contributions such as Mz* Baltazar's “Mud-batteries” and Juliette Lizotte’s “The Button Saga” are also rooted in actual situations, imbuing their reflexive stories with practical instruction. Juliette Lizotte recounts the eventful story of creating a seemingly straightforward interactive installation. The saga includes misunderstandings, pitfalls, and detours of working collaboratively, and negotiating diverging expectations and techno-social dependencies. Stefanie Wuschitz's graphic novel tells the history of the magazine Api Kartini that evolved from the Indonesian Women's movement GERWANI. The Api Kartini zines focussed on publishing and disseminating practical knowledge for Indonesian women in the 1950s and ‘60s around health, repair, fashion, self-defense, and negotiating better work conditions, but also contain elements of storytelling and poetry, and imagine alternative futures for women in Indonesia at that time.

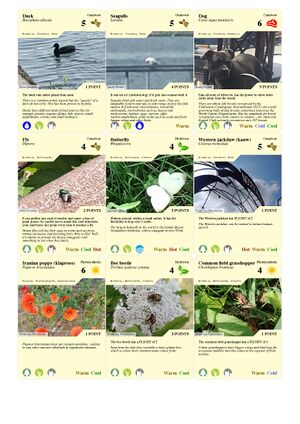

In “Display(ing)” the fanfare collective discusses the way a workshop script can be induced in an object. Through its material affordances, the modular display system designed by Freja Kir and Lotte van de Hoef carries its own script and has been enmeshed in the ongoing and morphing collective practice of fanfare, who have been traveling with the display since 2014.

The scripts and accompanying reflections collected in the cluster Distributed Curricula address aspects of time and duration, be it through timed exercises, through expressing a certain intentionality for continuation and longer-term engagement, or by paying attention to and taking as a starting point what is already there, the prevailing collective condition. Giselle Jhunjhnuwala reflects on the workshop Phylomon that catered to making and playing a cooperative game informed by local ecosystems. It addresses questions of longevity through the cooperative game mechanisms as well as the subject of building sustainable collective ecosystems, and durable ways of co-existing on planet Earth. The conversations “Interfacial Workhout” with designer, coder, and cook Sarah Garcin takes as a starting point one particular workshop instance and its residual effects within manifold workshop situations that followed. The text and accompanying scripts in “Scripting Workshops” further contextualize the notion of the “workshop script” in the context of the collective practice of H&D and reflect on our long-term commitment to organizing short-term learning situations.

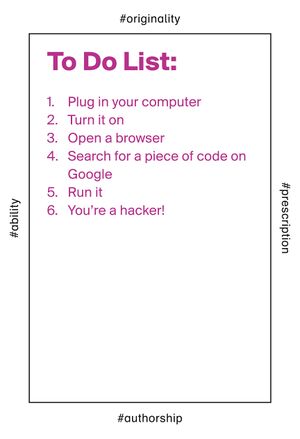

The contribution “Am I a hacker now?” by Loes Bogers and Pernilla Manjula Philip about their intergenerational Solarpunk workshop reflects on an ongoing exchange and multi-local process of developing workshop scripts in collaboration with two sister organizations Mz* Balthazar's lab and Prototype Pittsburgh. While departing from the shared goal of developing intergenerational learning formats about and around sustainable technologies, the evolving workshop scripts took shape and were reshaped according to their respective local communities.

The publishing tool “ChattyPub” evolved from and fed back into various workshop situations, of which the first one was hosted by Xin Xin and Lark VCR at the HDSA. The goal of the workshop, designing and building experimental chatrooms, sparked the idea among H&D to develop ChattyPub—a platform and tool for co-designing a publication that utilizes a chat environment. In autumn of 2021, H&D self-published the book Network Imaginaries, which was designed with ChattyPub. Among others, contributors included Lark VCR and XinXin, who wrote a contribution about their “Experimental Chat Room” workshop, featuring the various chatrooms that were built during their workshop. For this publication we reconnected with XinXin to continue our conversation about their practice as educator, artist, and activist, taking as a starting point the “Critical Coding Cookbook,” which they recently published together with Katherine Moriwaki. (See cluster 'Active Bibliographies')

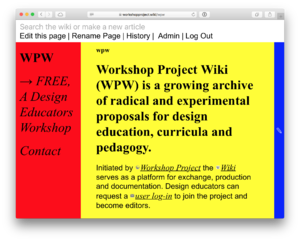

The ====== wiki reflections ====== by Yasmin Khan and Jessica Wexler look to the past and toward the future, exploring the ways a janky platform—the Workshop Project Wiki (WPW) developed by H&D (André Fincato and Anja Groten)—can shape a learning community for design educators. The very condition of the platform and its unfamiliar syntax transformed the intergenerational group of workshop participants into peers. After several iterations of the FREE educators workshop, the Wiki remains the key location for publishing prompts, documenting outcomes, editing a growing glossary, and planning future workshop iterations.

Contributions gathered under the cluster Active Bibliographies put forward careful selections of resources, generous catalogs, narrated reference lists, tips and tricks. They are active bibliographies because they are rooted in a sense of urgency and propose a shift. In “Critical Coding Cookbook,” Katherine and XinXin generously share their considerations and tactics of exploring their critical coding practices in parallel, local communities—informal educational environments that are multi-generational and non-hierarchical. Drawing on several “recipes” from the “Critical Coding Cookbook” they demonstrate multiple pathways to intersectional computing. Both contributions, “ChattyPub” and “Critical Coding Cookbook,” are exemplary of the inventive ways that collective practices initiate experimental and critical learning environments outside of or in parallel to institutional environments. And furthermore, they show how such conglomerates of critical makers and educators manage to create and sustain networks of like-minded practitioners—for instance through reusing code and methods, riffing off each other, co-organizing workshops, publishing and circulating their methods, and developing tools.

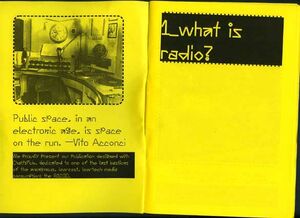

Petra Eros reflects on her experience of participating in the workshop + Rad I O by Mz* Baltazar’s Lab, which was further developed and hosted during the in 2021. She connects her workshop experience and the curiosities it sparked to various other initiatives with a stake in radio-making, and took her contribution as an opportunity to strike up an exchange with Good Times Bad Times community radio, which is published as part of her contribution. The contribution by Åbäke takes as starting point an assignment of a workshop hosted by Åbäke in 2010. In their email conversation Maki Suzuki and Anja Groten re-collect their workshop experience and reflect on their evolving pedagogical practices since.

Loes Bogers curated, edited, and commented on an array of resources that take as a starting point the question: How can we resist compliance with the unsustainable status quo of digital computing and electronics? The resources she draws together are accompanied by short personal reviews followed by short prompts that translate some of the concepts proposed into simple, practical exercises. This resourceful and active list evolved along with the Solarpunk workshop development trajectory.

Lastly, the conversation between Gabriel Fontana and Anja Groten took place while sifting through a pile of workshop scripts. Encountering these workshop scripts together and explaining what they meant to unravelled reflection on the various considerations that went into the specific workshops and their scripts, their different moments of activation, as well as their iterations.

Sifting Through a Pile of How-to's with Gabriel Fontana

Page from Workshop manual "Gestures in Transit," Gabriel Fontana, Vivien Tauchmann, 2021

Page from Workshop manual "Gestures in Transit," Gabriel Fontana, Vivien Tauchmann, 2021

Page from Workshop manual "Gestures in Transit," Gabriel Fontana, Vivien Tauchmann, 2021

Page from Workshop manual "Gestures in Transit," Gabriel Fontana, Vivien Tauchmann, 2021

Workshop Matters and Materials

In conversation with Gabriel Fontana

Anja Groten: Gabriel you and H&D are frequent collaborators. For instance you initiated Multiform—a non-competitive queer sports game during the H&D summer academy in 2019.[3] In this game, players are invited to change teams during the games through transformable sport uniforms. By allowing people to perform fluid identities, the game opens up space for experimentation, play, and collective reflection that challenge fixed categories.

Multiform, non-competitive game at HDSA2019 “Coded Bodies”

Gabriel Fontana: Exactly. Our collaboration unfolded around my research on how ideologies shape movements and vice versa. In particular, looking at how our bodies constantly propagate, internalize, and reproduce social norms.

“Channeling Listening workshop”, HDSA2021

AG: And there were a few other occasions our exchange continued. For instance, together with Vivien Tauchmann, you hosted a workshop about mobility and public space at the Design Department of the Sandberg Instituut where I work as an educator, and last year you hosted a channeling listening session on the last day of the H&D summer academy. [4] The last time we talked was on the occasion of a workshop I hosted, which was addressing the workshops as such. One of the sessions was dealing with what I came to refer to as a “pedagogical document,” which is a kind of genre of graphic design, but also a genre of design pedagogy and collective practice. Pedagogical documents could be instruction manuals, how-tos, scores, workshop scripts, game plays. These are documents to learn from and with. They are documentation of ephemeral learning moments but also cater to future use. You read my invitation to this workshop and kindly offered to send me your repository of pedagogical documents. I was very curious about them and more specifically about how they relate to your practice?

GF: Indeed, workshop manuals are at the core of my pedagogical practice. Year after year, I developed a collection of scripts that I designed for workshops and classes, facilitated in various contexts such as Sandberg Instituut; BAK, basis voor actuele kunst; and Design Academy Eindhoven.

AG: What is interesting to me is that these documents are not recipes or instructions for best workshop practices. They are highly contextual. So I thought it would be interesting to meet and go through our personal collections of these ephemeral scripts and how-tos, and perhaps talk about our shared fascination for them.

GF: I started to develop a workshop-based practice during my studies at the Design Academy Eindhoven. First, I was mainly facilitating short-term workshops related to my research on sport, physical education, and queer pedagogies. These workshops were not required to be printed as a script. At times, the script was directly embedded in sport tools I designed such as the transformable uniforms or alternative sport fields. After that I began to extend my pedagogical practice to other topics and formats, which required me to find other structural tools such as workshop manuals.

AG: Did you make the documents you brought?

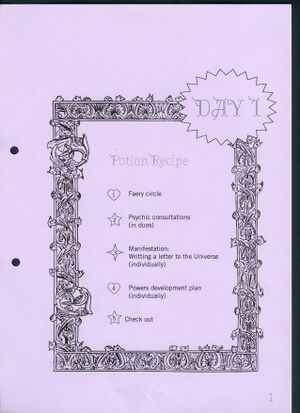

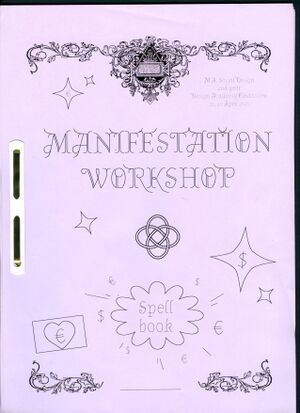

GF: Yes, I have been making these for the past four years. Let’s start with the manual I made for the Manifestation workshop that I have been running at the Design Academy Eindhoven since 2021. It was a professionalization workshop that invited master’s students to play with manifestation techniques, astrology, and the vocabulary of psychics as tools to explore the potential of their postgraduate journey. What I find interesting with this manual is that it is not a dead object but a document that integrates participants' feedback and keeps on evolvingand being updated year after year, workshop after workshop. Designed as a spell book, this manual provides incantations, recipes, instructions, tarot reading, and diverse resources. Therefore, it does not only offer practical information but also helps to set a specific narrative for the workshop.

“Manifestiation” workshop manual, 2021

AG: lt is an incredibly elaborate document. It reminds me of this other one you made with Vivien for the Gestures in Transit workshop, which I have here in my document pile.

Anja's reference pile of pedagogical documents

GF: This workshop was looking at how the design of public transport shapes our freedom of movement. Therefore the aesthetic and structure of this manual is very different from the one I made for the Manifestation workshop.

When I develop and structure a workshop I consider how to use both the visual codes and language related to the topic. For instance, for the Gestures in Transit manual, we literally used the layout of the train schedules to structure the workshop, which, as is public transport, was really strict in timing.

Workshop manual "Gestures in Transit", MA Design, Sandberg Instituut Amsterdam, Gabriel Fontana, Vivien Tauchmann

AG: Its function is to create a shared experience, a world within which the workshop takes place.

GF: Definitely. And it can also create excitement among participants. I always love the reaction when I bring the pile of manuals to the group. This makes them excited about the workshop and they see the value in it.

AG: It is a beautiful gift you bring and also shows a commitment towards the time you share with the group of participants.

GF: Yes, and for me taking the time to prepare and design the workshop manual is also an exercise of care, in a way. It helps me to put myself in the participants’ shoes to imagine how they might receive and understand certain instructions. In this way, it also helps me to imagine myself within the space.

AG: Such a document is a flexible information source and structures the workshop. Individual participants, if they feel the need, can gain more structure, or just let go of the document and go with the flow.

GF: It offers them a timeline and a clear understanding of where we’re headed. In addition to this, I also see the manual as a script to activate the group. When we come together in my workshops, we always start first by reading out loud the synopsis of the day. This small text introduces the main themes that we will explore. Once everyone has entered the room and I feel that the group is ready, I just start reading it so people understand that the workshop is starting without me having to announce it.

AG: Like a ritual! At some point they will also know, OK, he's picking up the manual. It's going to start again.

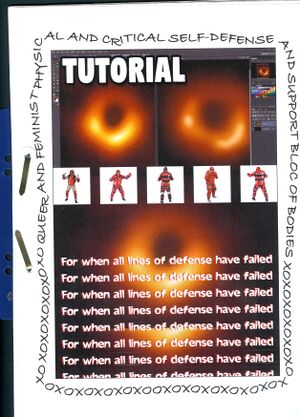

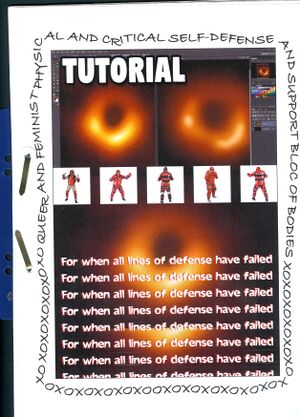

GF: I also brought another workshop manual that we designed with Clara Balaguer and Sarafina Pauline Bonita for the QFPCSSBBXOXO (Queer and Feminist Physical and Critical Self-Defense and Support Bloc of Bodies) workshop we facilitated together at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, in 2019. This five-day training explored different techniques for channeling voices as a tool to deeply listen, share, and heal traumatic experiences related to patriarchal violence.

Tutorial for QFPCSSBBXOXO (Queer and Feminist Physical and Critical Self-Defense and Support Bloc of Bodies), Clara Balaguer, Sarafina Pauline Bonita, Gabriel Fontana

AG: I remember that you introduced some of these channeling techniques during your last performance and workshop at H&D summer academy in 2021. Could you tell more about how the method of channeling relates to the topic of self defense?

GF: In the case of this workshop, we were talking about trauma and violence, and asking how one could inhabit the retelling of experiences of violence in a way that is less violent, that does not re-traumatize. As a speaker of uncomfortable things, when you’re hearing, seeing, or otherwise sensing audience feedback, it can be difficult to hold your thoughts in the way that you want to hold them and express them with resolve. When you’re picking up on audience reactions—even empathic responses can be distracting—this distorts or amplifies what you are feeling, making it laborious to continue. In this context, it was important for us to develop tools that allow us to share personal and difficult stories with an audience without being directly confronted with them. This gave way to the technique of channeling, a tool that allows you to talk through the body and voice of someone else and therefore to communicate with an audience without having to be present in the room.

AG: I feel like through these kinds of methods, workshop knowledge travels through many spaces and contexts. But at the same time they are so specific and contextual. The story you are telling me about the motivations behind channeling seems significant to the method and to the workshop topic and experience.

AG: This document here, its a method for feedback by a performance scholar Liz Lerman. It is called the “Critical Response Process”—Actually, I think there is copyright on it. But there is quite some documentation of the method online—which I have started using in my classes. I tried some of these methods with my students and reflected on the method with them. I found there was a bit of resistance towards being directed and guided by strict methods, perhaps this is particular to the environment of art and design, education, and these self-organized learning spaces we are both engaging with. We don’t want anybody to tell us what to do! But if there is some kind of mediation as well as a certain malleability to the script, and attention to different modes of interpretation of these exercises, maybe rewriting them together can be quite a fruitful learning instrument. Learning experiences in practical education like art and design can sometimes be latent and not so explicit because it's not necessarily articulated. A pedagogical document and a certain commitment to it can make the implicit explicit somehow. It can turn a situation of doing things together into a critical and conscious learning experience. That is, not by itself but rather through its activation.

I wonder what ways that such workshop scripts could be disseminated in response-able ways, with attention to their iterative potential, their histories, and future use. It's not necessarily about authorship or crediting, but about how and why these methods were activated and in which context. To me, it is so interesting to hear how you relate to channeling as a method, and it makes apparent that it is a method that cannot just be applied to any context, like you’d “execute” a script or “run” an algorithm.

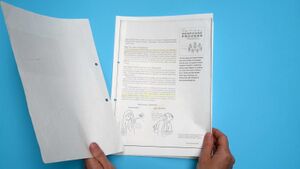

Still from a video, handling the a printed copy of the "Critical Response Process," Liz Lerman

AG: Look, this script has been with me since 2010.

GF: Wow, and it's still alive.

AG: It's a workshop prompt by the design collective Åbäke. I've used this method several times before. I usually explain where it came from and why it was useful to me. It's a small gesture. Åbäke came as guest tutors to host a workshop at the design department of the Sandberg Instituut, where I studied between 2009 and 2011. They made us hijack each other's research projects for two days. That was it! The education at the time was rather focused on individual research trajectories. Every student was supposed to have their own research project that you work on for the duration of the two years. The way the course was structured was building on students self-organizing and working in a self-directed way. For me this approach was actually rather challenging. I was quite lost and I found it really hard to push my own agenda... because I'm very receptive to my environment, and I like to do things together. It was such a relief that I could just hand over my project to someone else and get someone else's project for two days. This small intermission gave us permission to step out for a moment. It really influenced a lot of people's trajectories. And I've used this method many times since.

“A Case of Mistaken Identity”, workshop assignment by Åbäke

The Åbäke script is an interesting design object. These documents, workshop manuals, and how-tos also, in a way, have their own kind of graphic design rules. On the one hand they are well taken care of: they are concise and easy to reproduce with regular office supplies, which makes them also easy to rework, annotate, and appropriate.

GF: That reminds me, usually I share these manuals not as a .PDF but as a scan of the printed object, so you can see the color of the paper as well, and workshop participants really receive it as an object.

AG: Interesting, I too have thought about tricks to better contextualize these documents and their moments of activation, their liveliness, and the different transformations they go through. For instance, I made videos in which I tell the stories of the documents while holding them in my hand, sifting through them, so you see them being touched and activated.

In our last H&D publication, Network Imaginaries, we published workshop scripts but we did this in a way that all the scripts became uniform. In retrospect I think this flattened them, and we lost their moment of activation and the memory of them as well.

GF: I think I was not so aware of why I was scanning them. But indeed the materiality and reproduction tells us a lot about how to understand such an object, and how to relate to it.

AG: And yet, I think the facilitator—and their sensitivity in activating these manuals—seems crucial for such a document to be purposeful.

GF: Definitely.

AG: There have been times when I thought I had come up with the most amazing workshop and then when I ended up in the space, and while trying to activate it, I realized, oh, I've assumed a lot here. For instance, a common knowledge, or that I’ve assumed there is a sort of common ground in a group from the start, perhaps a shared interest, solidarity. But sometimes through giving workshops, especially because they are temporary and very quick, you end up rushing through those assumptions.

Within your practice–and I relate to this as well to some extent–there seems no separation between being an educator and being a designer. These workshops you are hosting, while they may be short encounters, are never really just a one off thing because you build a kind of body of work around them, they are all connected in a way.

GF: That’s why documentation is such an important question. For example, it was difficult for us to document the queer, feminist self-defense workshop, so the manual became the documentation object of documentation.

AG: This really resonates with me. Often I don’t do anything with the outcome of a workshop I facilitated. These so-called outcomes don’t seem to be meaningful outside of the context they were produced. It produces a certain result, or something to work towards, which seems to be necessary in the moment for a process to take place, but not as a means to an end. And therefore these materializations, sketches, and prototypes, are perhaps not for everyone's eyes. I'm always questioning what ways to document and disseminate this kind of ephemeral workshop practice. I do think from the way you explain your considerations and experiences, that it is important to understand the context, who was involved, how, and where these scripts were really activated.

GF: I taught for the past three years at Willem De Kooning Academy in Rotterdam. There you are asked to bring your own personal practice into the development of the curriculum. However sometimes the curriculum and exercise instructions you develop get passed on to another teacher. I feel some tension here. On the one hand, I believe in open-source education, but on the other hand the knowledge and tools that you bring to the class always come from a specific context and are therefore always situated. Maybe we need to start designing manuals about how to disseminate our workshop manuals.

AG: In a way, this publication is an attempt to think about other ways of disseminating such documents. It's not just about sharing these scripts as they are, but taking specific pedagogical documents as a starting point for engaging in conversation. Maybe we will be showing bits and pieces of the documents, show them in action, perhaps, narrated, iterated, annotated, discussed, in order to situate them a bit more.

I have been experimenting with the idea of facilitating a workshop where there is no facilitator, where it kind of runs itself. People get into groups and they get this kit where they have to follow the prompts and make sense of the workshop together. There's definitely a limitation to this approach, but it's an interesting exercise to thoroughly script a workshop in such a detailed way because you create documentation already and have to imagine the situation much more vividly.

GF: It's also interesting to see at the end how people interpreted the instructions. Another thing that I always try in my workshops is to demonstrate as much as possible. For example, when I facilitated the channeling workshop at H&D summer academy in 2021, I started with a performance that demonstrated the channeling technique. The participants at first didn’t really understand if this was just a “normal” conversation between two people or a performance following a specific script. It was only once the performance was over that the script and the channeling technique were revealed, which then became material for participants to play and experiment with.

AG: This one is also an interesting script. It is an example of how the layout of a specific document can afford a particular interaction with it.

Annotated Maintenance Art Manifesto, from a workshop by Annette Krauss, hosted at the Sandberg Instituut Amsterdam

GF: There is a lot of space.

AG: Indeed. You can imagine yourself just scribbling on it, working with it. Sometimes when these scripts are too beautiful they don’t afford that.

AG: This document is actually the script of the workshop that I invited you to, and which started this conversation.

The scripts exists and was activated in several iterations. In this particular iteration I asked friend and performance artist, Pia Louwerens, to host my workshop. She also works with scripts in her practice. Somehow, she could connect all the points I was addressing in the script to her own experiences. She had her own ideas about it, so she kept the original script intact, but copied it, leaving plenty of space on the left and right. Then she annotated it for herself, and hosted the workshop. I was there as a participant. She followed the timeline of the script but then, for instance, for the introduction, she gave her personal introduction to the workshop, and explained how it relates to her practice as an artist working with institutional critique, arguing that scripts are always already present. In her work, she works with hidden scripts (literally or figuratively) of institutions—constantly negotiated and questioning what is expected of an artists by an art institution and vice versa—and then she was hired by me to give this workshop, which presented yet another script to negotiate with. In this workshop, she somehow managed to reflect on all of these different layers of the scripts-in-action. It was quite mind-twisting to participate in my own workshop, but also incredibly insightful.

GF: I guess it’s a nice way to get some perspective.

AG: Yes, exactly. And also it created a kind of discourse around this kind of pedagogical aspect of people’s practices.

GF: I love this collection of manuals you have.

AG: I'm working on a kind of bibliography of these documents for this publication, to republish them, in a situated way, and emphasizing the stories they are connected to.

GF: Clara and I have this thing going on, where we swing new manuals to each other. We should really bring them together once and do something with them!

AG: Let me know! I want to be part of that meeting!

Gabriel Fontana is a social designer. He is the initiator of Multiform, a tool that challenges and examines ideas of identity, community, and inclusion by proposing games for sport classes at schools, generating an openness and empathy that later on filter into wider society. Through a queer framework, Fontana investigates how daily social practices reproduce conservative values and reinforce power structures. Within a phenomenological approach, he develops performative design research, positioning the body as the central perspective from which the social world is experienced, reproduced, and challenged. Fontana lives and works in Rotterdam.

Anja Groten's bio.

Learning Experiments, Exchanging Techniques

Learning Experiments

Workshop Histories and Practices

In her talk "The Workshop as an Emancipatory Mediation Method of Resistant Practices" political activist Hanna Poddig referred to the

discussion scores that are also common in Consensus Decision-making practices

"A section of Water Walk," score by John Cage

Notes by Suzanne Lacy on the ongoing civic engagement in Oakland and the Oakland Youth Policy Initiative. Image courtesy of Suzanne Lacy.

Workshop Histories and Practices

In conversation with Heike Roms

Anja Groten: In May 2021 I participated in an online conference titled “The Workshop as Artistic-Political Format,” organized by Institute for Cultural Inquiry in Berlin.[5] The conference drew together practitioners from various fields of interests, including choreographers, dancers, theater makers, artists, scholars, musicians, and activists who reflected on “workshop” as a format, site, and phenomenon from their own perspectives. Heike, you gave the presentation "The Changing Fate of the Workshop and the Emergence of Live Art,” which particularly resonated with me.

Heike Roms: I came to the topic of workshops because in my work I look at the emergence of performance art in the sixties and seventies. I became interested in particular in the emergence of performance art within art educational contexts, in a conceptualization of a pedagogy of performance. I've read your chapter on “Workshop Production,”[6] which I really enjoyed. Some of the research you've done is helpful to me because I too have found that there's actually very little written about the workshop as a practice. That is, people have written about specific workshops so you can find material on workshops given by a particular artist. But there is little reflection on the workshop as a format, as a genre, as a site, as whatever we might call it. That surprised me, given that it's sort of ubiquitous in practice. There are books on performance laboratories, for example, and there is a connected history between the workshop and labs, the studio space, and rehearsals as a format. But there is very little on the workshop, certainly within performance studies or art history discourse, so I became intrigued by this ubiquitous form that remains largely unexamined. It's great that through the work of Kai van Eikels and the 2021 conference he co-organized there's a new kind of attention being paid to it, through your work as well. But there is not enough available about the history of the workshop to help us understand at what point this flip occurred from considering the workshop as an actual physical site to approaching the workshop as an event format. You write about this as well. The two meanings, of course, continued to exist in parallel, particularly in the context of art schools. But at what point did the workshop become an event, a time-based learning experience, as well as a site of making—a Werkstatt? I don't know how and when that occurred. My suspicion is that it was sometime around the fifties and sixties.

AG: There is the The Journal of Educational Sociology that was published in 1951 and refers to the first organized professional education activity under the name of a workshop. It took place at Ohio State University in 1936.[7] I remember you were talking about the relation between the occurrence of workshops and the emergence of a certain resistance toward the steady structures of art schools in the fifties and sixties in the UK—a resistance to legitimized knowledge practices and skills. Art students wanted to rid themselves of a certain authority of disciplines or disciplined learning and instead wanted to take things into their own hands.

HR: In the specific history I looked at, which is that of Cardiff College of Art, I found that there is a confluence between the workshop and two emancipatory movements. First was the move toward the workshop as a learning format through the impetus of the Bauhaus, which in the 1960s developed a huge impact on art schools across the UK. Traditionally people weren’t really talking about workshops as sites of making in the context of art schools; the workshop was the place of the plumber or the blacksmith, while artists worked in ateliers or studios. I think that the idea of the workshop as a place of making was introduced to the art school through the Bauhaus philosophy, which was a vehicle for the emancipation of art education. All of a sudden art was being approached in the same way as other practices of making were being approached. No longer did we have the sculpture atelier or the drawing room. Now there were ceramics workshops, metal workshops, printmaking workshops but also painting workshops and sculpture workshops (or ‘2D’ and ‘3D’ workshops as they were often called at the time). This move introduced a different kind of art making.

This change that occurred in art schools in the UK in the sixties through a new approach to art education known as ‘Basic Design’ was very much driven by the reception of the Bauhaus approach and in particular Joseph Itten’s Vorkurs (preliminary course). Workshop production was seen as a new, more emancipatory form of art making. It came out of the experiences of the Second World War and the desire to give art students a different sort of experience—one that connected them to the contemporary world rather than traditional skills training and that aimed to overcome the distinction between art, craft and design.

The second shift is where performance comes in in the 1960s. Teachers and students saying: We don't want all of that material making in the workshop. We want to make something that's ephemeral and that's collective and that's participatory. We don't want to be hammering away all day in the workshop. Instead we do this other thing where we get together and we make something that’s not actually about producing any objects, and we'll call that a workshop as well. That's the event-based rather than space-based concept of the workshop.

In dance, people were already talking about workshops as events in the fifties. I don't know when the shift occurred from the workshop as a site toward the more ephemeral understanding of the workshop as event, how that happened, but it's interesting because what motivated the artists in the sixties that I have been looking at—and they explicitly say so in their notes—was that this move toward the ephemeral was about searching for more equitable relationships that do away with the teacher-student division. That division had been further cemented by the remains of the Bauhaus philosophy and its celebration of mastery. I think that was one of the key shifts toward this more ephemeral meaning of the workshop. It was no longer about a master passing on knowledge to their students. It became about collective making. And everybody took collective charge and responsibility for that making. The educators on whom I've done research actually say that they wanted to get away from producing objects toward collective action. But, as you say, the workshop can very easily be co-opted like so much of the sixties was. Was that the last hurrah of collectivism? Or was it actually what lay the groundwork for the entry of neoliberalism into education as we now know it?

AG: I myself am wondering whether organizing workshops can generally be considered an emancipatory practice at all? Perhaps there cannot or should not be a general answer to this question. At the school where I work as an educator, some argue the educational system builds upon rather precarious labor conditions, where everyone works as a self-employed freelancer. Simultaneously, more and more workshops are being organized, which at times can clutter the education. Students are supposed to self-initiate and self-organize as well. They often resort to organizing workshops for each other. In my view, such conditions sometimes also show the limits of what can be accomplished with workshops. I think it's important to have more discussions about the workshop as a format and its implications for the learning economy. How to speak about and practice workshops in a way that still allows us to do the things we want to do, whilst also paying critical attention to the undesirable conditions it is intermingled with.

How was it for you? Did the invitation to the conference lead you to take a deeper look at the phenomenon of the workshop? Or were you already busy with it?

HR: Yes, it would be fair to say it led to a deeper engagement with the notion of the workshop. I had been working on this material before and I've written about it too. But I had never really paid attention to the frequency of the word ‘workshop’ in the material I had researched until the invitation came to speak at the conference. It was then that I realized that the workshop is a really productive format to be talking about.

I wrote a paper on this before in which I talked about the idea that artists and performance educators in the sixties and seventies in the UK were creating events as a kind of parallel institution. These events aimed to serve the function of an art school without replicating its hierarchical structures. This was the case in Cardiff, but also in other places in the UK such as Leeds College of Art. I was grateful that I was invited to think more about this by the conference. I looked at my examples, and it is specifically “the workshop as event” that emerged as a kind of parallel institution at the time. It wasn't really the performances these teachers and students went on to make together, but the workshop as a learning format that I think they clustered all their ideas around.

AG: I stumbled upon the conference last minute and wasn't aware of this whole community of performance artists and live arts who consider the workshop as an artistic medium. It's also interesting that the workshop, because of its ambiguity, manages to converge all these different worlds and unveil commonalities between them. For instance a policeman[8] speaking about their conflict resolution workshops, and the activist who learns about tying themselves to a tree and how to negotiate with the police while doing so [9]. Both speaking about the same sort of thing at the same conference from an entirely different vantage point.

You emphasized that a lot of the artists you researched were also educators. It was great to hear that engaged with in such an explicit manner. I don’t often hear about how the practices of artists and designers continue to evolve within particular educational environments, after they have completed their studies too. I find that many great artists and designers are also teachers and I personally don’t draw a harsh distinction between being an educator and being a designer. The practices go hand in hand. But I found that there are not many records of the teaching practices of artists and designers. Another thing from your talk that really stayed with me was your re-enactment of a workshop. You showed some pictures and I found them so interesting and also funny. In your re-enactment, you imagined through physical exercises what the workshop might have looked like. You referred to one specific artist educator, whose name I don’t recall.

HR: His name is John Gingell, and he is not particularly well known. I never met him in person, as he had already passed away by the time I became interested in his work. He had a sculptural practice, and a few of his public artworks are still on view in Cardiff, and some of this work has been exhibited in London. But really he was an educator. That was his main practice. He formed and shaped generations of art students. He was not the type of person to write manifestos, or write a lot in general, but I've been very fortunate because his family has allowed me to look at all of his materials, which are now kept in the attic of one of his daughters. He didn't leave a written philosophy of teaching or anything like that, just really random notes or little statements that he put together for the art school in order to justify what he was doing, or presentation outlines and things like that.

I didn't re-enact any of his workshops because they were very sketchily documented. He was not somebody who kept a particularly developed documentation or scoring practice. If I think about my own teaching, I don't either. When I enter a classroom, I often just jot down some notes on the exercises I want to do. They're just little prompts, which aren’t accompanied with much explanation. In years to come, if somebody were to look at my teaching notes, they too wouldn’t be able to make much sense of what I was doing in the classroom. I don't think that's unusual. Anyway, I have contact with one of Gingell’s students from the late 1960s, the artist John Danvers, who also taught at the art school for a number of years in the seventies. He was very influenced by John Cage, so his own artistic practice was already very score-based. When he became a teacher his teaching practice was very well documented. He documented the exercises alongside photos of the students doing the exercises. He has quite substantive documentation on the courses he taught at Cardiff.

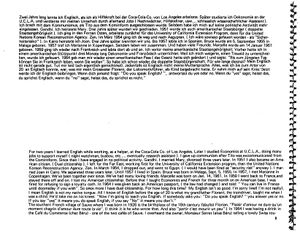

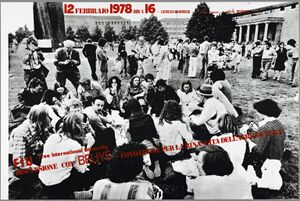

Interestingly, one of his regular classes in the early 1970s for Cardiff College of Art was a workshop about the use of sounds and words, which was unusual for an art school context. I invited him in 2013 to re-enact the workshop as part of the Experimentica Festival in Cardiff. Anybody could attend, but it was mainly my friends who came [laughs]. A lot of the people who attended were theatre people, and their feedback was that Danvers’ exercises and the approach that he took spoke very much of a visual arts kind of sensibility. Even though he was working with words and sounds—which have a theatrical dimension—their purpose was much less about what theatre workshops tend to focus on, such as the interpretation of words or meaning-making. Instead, Danvers’ workshop was much more about the visual qualities of words and sounds. There was much more concern about spatiality and the sculptural qualities of words. Danvers approached his teaching practice very much as a conceptual practice, and so it was fairly easy to reconstruct what he did in his workshops. I've always been intrigued by this hidden history of pedagogy within the emergence of experimental art. We read a lot about John Cage and his teaching at the New School in New York, but I often think, what did they actually do in his classes? There are some accounts of his students about the improvisations they did with Cage, but very little. I'm intrigued to learn more. Beuys too was a teacher as well as an artist, who considered teaching his ‘greatest work of art’ and a key part of his practice. There are others, too, like Suzanne Lacy and Allan Kaprow, who both taught at CalArts. In fact, a lot of the canonical performance artists were also often teachers. Some of them, Kaprow, for instance, also wrote about education.

AG: I was also wondering about how you document workshops. As you said yourself, even though you come up with the initial class or workshop, it is to a large extent shaped in the actual encounter with the people, materials, and space itself. It is obviously not so interesting nor meaningful to just take pictures of people having a great time. So what are ways of documenting that afford a continuation of whatever is happening in these short workshop encounters, and which allow for retrospective discussion and reflection of these workshop practices? The way I document workshops is usually very messy. Our workshop archive is scattered in different places, online and as well as offline.

I was wondering, sometimes we compare workshop scripts with protocols and orchestrate physical re-enactments of what a computer would do, translating something that happens in your machine into a physical space. I am not very familiar with scoring practice but what I do know makes me think of protocols or algorithms. It's not a recording or a replica of a situation, but it sort of anticipates it, sets conditions. I wonder if it could help us think about documentation as something that is not only about looking back, but in fact geared toward continuation and activation in the future.

HR: From the sixties onwards, through Happenings and Fluxus, practices of scoring actions have become a common device in visual arts. And in performance art and dance, very extensive scoring practices have emerged. The indeterminacy of the score or instruction is partly what interests artists. You give somebody a score, and it could be interpreted in a hundred different ways. That's why it is interesting to consider where the artwork is located in these practices. Is the score the artwork? Is it the realization of the score the artwork? A Fluxus score, for instance, wouldn't even tell you how many people have to carry it out. Such a score could be about the very indeterminacy of an action.

Traditionally, we think of the author of the score as the author of the work, such as in musical compositions, for example. But more recently, we are seeing much more experimentation with scoring practices, and with the relationship between the score and the event or action that it might anticipate or generate. A few years ago Hans Ulrich Obrist did a large-scale curatorial project called “do it,”[10] which invited artists who don't normally have a scoring practice to write their own scores or instructions. People were invited to enact these score and then upload documentation of the enactment online so that you could see the score, as well as a multitude of different kinds of documentation of the different kinds of outcomes produced by their enactments.

AG: I am trying to think through the question of how to publish something like a workshop or a workshop script. In my view it can be an interesting graphic design object because it's very unresolved, very spontaneous, it's actually not a precious object, and it’s never up to date. These criteria are significant for it to function. But how do we publish something like that in a meaningful way? For instance, pictures of workshop situations can help to contextualize something like a score or workshop script. You cannot just give the score to someone and expect them to know what they have to do and how to be excited about it. You need that activation moment and know-how too. But including snapshots of people doing things is not necessarily interesting to print in a book.

HR: It brings us back to the fact that there are different kinds of workshops and different kinds of scores. There are those that are meant to be indeterminate and generate lots of different kinds of responses. Every response is justified and equally valid. Sometimes visual documentation can therefore be too prescriptive. If you see a score and somebody enacting it, you might think, well, that's the only way to do it. It takes a little bit of your agency away. Unless you do it like the DIY “Do It” project, where you provide the documentation of multiple enactments so you encourage people to try their own response by showing them five different versions. But then there are also scores where which are much more prescriptive, and people want them to be enacted in a particular kind of way, particularly often in pedagogical contexts. Do you want the exercise to land in a particular way, because you want the students to have a particular kind of learning experience? There are different scoring practices, different ways to shape an instruction, and similarly there are different kinds of documentation practices that might be suitable. Yet, I would say that it's the “doing,” the activation and interpretation of a score, that's interesting. It's all about the finding process and the kind of rationalization and reflexivity that you go through in this process that I find exciting. It’s often just as interesting to look at how a person struggled through finding a response to a a score or instruction than the response itself.

AG: You also teach workshops for children. What are they about?

HR: I have been involved in some performance work with children through my collaboration with the artist Sibylle Peters, who runs a theater for children in Hamburg, the FundusTheater/ Forschungstheater. Sibylle calls it a “theatre of research”.[11] The philosophy is that research is something that brings artists, children and scholars together, as it's something that artists do, it's something that children do, and it's something that scholars do. She devises projects around different themes which are of particular interest to the children she researches with and are often driven by their desires, such as ‘I want to be rich’, which led to an examination of the nature of money and the founding of a children’s bank with its own micro-currency in Hamburg. I did several projects with Sabine, where I was invited for my knowledge of performance art history. The last project we did was, Kaputt – The Academy of Destruction at Tate Modern in 2017. Destruction is a really big subject for children, because they're often told they are destructive or have destructive behavior.

We worked with children who were diagnosed with behavioral issues, who showed what was deemed destructive behavior in class, or who were really interested in watching cartoons where things get destroyed. Kids see and hear about destruction all the time, for example the destruction of the environment. When we were doing the project in London, seventy-two people had recently died in the Grenfell Tower fire as a result of negligence.[12] It was close to where the children we worked with came from, and it was very present in their minds. But there's no real outlet for children to explore their fears about destruction, but also their interests and pleasures in destructiveness and their destructive fantasies. We worked with the children on the notion of destruction for a week. We were all considered equal experts on the subject, and we all shared our expertise. The kids gave talks, for example about destruction in comics and animation. I gave a talk on destruction and art. Sybille has done lots of these kinds of projects, which I occasionally get invited to participate in and work on issues that overlap with the histories of art. Inspired by our work together, I have recently begun to research the participation of children in the history of avant-garde art, especially in the performance practices of Happenings and Fluxus.

What is important to Sibylle as well is this idea of the workshop as a space for equitable relationships. She takes seriously what the kids bring to the discussion. And it's always about rethinking and reshaping the adult-kid relationships. We will be working together again in September 2022 on the occasion of the opening of a new building for the Fundus Theater in Hamburg. For that event I am currently working on some research that looks at child activism in the sixties, especially the involvement of children in the American Civil Rights movement, and how that intersected with children's participation in experimental art projects at the time. How children were trained for their participation in protest or art with the help of workshops will be a major aspect of this research too.

Heike Roms is Professor in Theater and Performance at the University of Exeter, UK. Her research is interested in the history and historiography of performance art in the 1960s and 1970s, especially in the context of the UK. She is currently working on a project on performance art’s pedagogical histories and the development of performance in the context of British art schools.

Scripting Workshops

Worksheet for “An Automatic Workshop,” collaboration with Shailoh Philips during the H&D Summer Academy 2018, Amsterdam

Worksheet for “An Automatic Workshop,” collaboration with Shailoh Philips during the H&D Summer Academy 2018, Amsterdam